County Wexford man Hugh Walter McElroy served as Chief Purser on the Titanic and sadly perished during the tragedy.

Editor's note: On April 15, 1912, the Belfast-built RMS Titanic sank after colliding with an iceberg, killing over 1,500 passengers and crew on board. This was one of the deadliest commercial peacetime maritime disasters in modern history and among those on board were many Irish.

This is an extract from the book “The Irish Aboard the Titanic” by Senan Molony which tells the tales of the people who were on board the night the ship went down. This book gives those people a voice. In it are stories of agony, luck, self-sacrifice, dramatic escapes, and heroes left behind.

Chief Purser Hugh Walter McElroy

From: Tullacanna, County Wexford.

Polygon House, Southampton.

Being Chief Purser on the Titanic was a huge responsibility – and it was filled by an Irishman who was larger than life and the last word in gallantry.

Hugh McElroy occupied a critical shipboard position for the White Star Line. As Purser, he was the company’s main interface with the bulk of passengers. They came to his office on C deck for everything – to lodge and retrieve valuables for safe-keeping, to hand in wireless messages to pass on to the Marconi room, to report a leaky tap in a stateroom wash-hand basin, to organize a game of quoits on deck, right down to buying a ticket to the Turkish bath on F deck, and yes, renting the deckchairs ($1 per voyage).

McElroy was the perfect man for the job because he clearly was an effortless arranger even during his short stays on shore. On April 9, while still in Southampton, McElroy and his Wexford-born wife, Barbara, sent flowers in the Danish national colors of red and white to Miss Adeline Genée, a famous dancer.

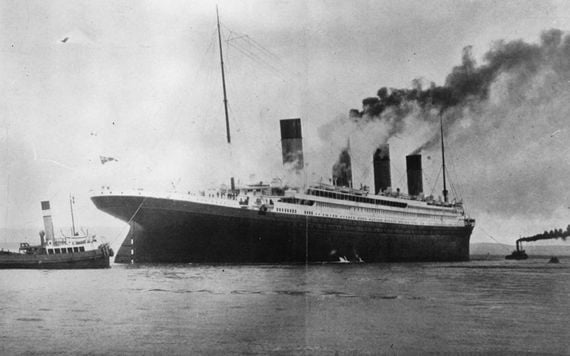

The RMS Titanic.

Perhaps she had been an important passenger in the past, but the gesture was particularly polished given the fact that Miss Genée was due to perform a special ‘flying’ matinee at the Southampton Hippodrome two days later – the afternoon after the Titanic sailed.

McElroy was still oozing charm and goodwill at Southampton when Francis Browne, the clerical novice soon to become famous for his photographs on board the Titanic, called to his office on C deck, ‘where a letter of introduction served as a passport to the genial friendship of Mr. McElroy.’

The soul of urbanity, McElroy was also a favorite of Captain E. J. Smith, and the two men were photographed together on deck, the Purser appearing with his hands joined behind his back, an image of strength at the master’s right hand, and ever ready to do his bidding.

The Cork Examiner, which took the famous shot, noted in its issue of April 15, while unaware of the unfolding tragedy:

On the right of the picture is Commander E. J. Smith, R.D., R.N.R., to whose skill and watchfulness is committed the care of the great ship and her freight of close on four thousand souls. He is one of the heads of his profession, and he has a long and extensive connection with the White Star Line. The Captain may be the best, but unless the Purser knows everybody and everything, and combines the perfection of urbanity, tact, prompt appreciation of circumstances – in fact, is the best of fellows – his passenger list does not fill all the time, but on any ship on which Chief Purser McElroy has filled that position, the booking has always been complete well in advance of the sailings.

Love Irish history? Share your favorite stories with other history buffs in the IrishCentral History Facebook group.

In fact, the Titanic was by no means full. But that simply allowed McElroy to indulge his special charm with the ladies. Mrs. Henry B. Cassebeer recalled visiting the Titanic’s Purser soon after boarding to ask for an upgrade from Second Class. It was done at once and Mrs. Cassebeer ended up with one of the finest First-Class staterooms ever created for ocean-going luxury, the bulk of which was on this vessel. She remembered running into the Purser a little later and, pushing her luck, asked that it be arranged that she should dine at the Captain’s table. McElroy’s reply, quoted in Walter Lord’s "The Night Lives On," was: ‘I’ll do better than that. I’ll have you seated at my table.’

On that fatal Sunday, just after midnight, when the Titanic engines had stopped after impact with the iceberg, bathroom steward Samuel Rule was investigating the oddity when he saw Purser McElroy on A deck ‘in deep conversation’ with Second Steward George Dodd. He expected to receive orders, but none were given.

A photo of the iceberg which the Titanic struck.

At ten past midnight, stewardess Annie Robinson saw McElroy accompany Captain Smith in the direction of the mailroom, where water was within six steps of coming up onto E deck. ‘About a quarter past twelve, or round about that time’ Second Steward Joseph Wheat was going up to C deck when he met McElroy looking over the banisters. ‘He saw me coming and told me to get the men up and get … lifebelts on the passengers and get them on deck.’ The Purser had been talking urgently to two or three officers, including Chief Steward Andrew Latimer. At ten minutes or a quarter to one, Wheat was again given orders by McElroy, to get all the men to their stations at the boats.

McElroy’s communication skills were at the fore when disaster struck and the Captain needed trusted men about him. There is evidence he played a major role in harnessing the passengers to their task of putting on lifebelts and preparing to abandon ship. Quietly, too, it seems he was passed a loaded revolver. Although not strictly one of Smith’s officers, McElroy had assumed a position of veiled yet real power.

He was next seen outside his office on C deck, where a queue for valuables had begun and was being quickly processed by assistant pursers who emptied the safe. He later addressed the crowd, who were standing around in confusion, urging them to go up top. The Countess of Rothes moved close by and McElroy declared: ‘Hurry, little lady, there is not much time. I’m glad you didn’t ask me for your jewels as other ladies have.’

McElroy followed his clucking flock, then returned to his duties. He was later seen in the company of his fellow Irishman, Dr. W. F. N. O’Loughlin, the senior ship’s surgeon. Soon, however, he made his way to the boat deck, where chaos reigned and where every man of authority was desperately needed. McElroy answered the call.

Saloon steward William Ward witnessed Mr. McElroy with First Officer Murdoch and J. Bruce Ismay, Managing Director of the White Star Line, at boat No. 9 on the starboard side. ‘Either Purser McElroy or Officer Murdoch said: “Pass the women and children that are here into that boat”,’ said Ward. McElroy next ordered himself and bathroom steward James Widgery into the boat ‘to assist the women’. They went.

Before anyone left on board could draw breath, it was nearly 2 a.m. Just two boats remained on the starboard side, with a collapsible hanging in the davits perilously close to the slowly submerging superstructure. A crowd had surged down to it, milling about the restraining officers and crew.

Elsewhere McElroy was bestriding a boat half-lowered to A deck, one hand clutching a fall rope, another wielding a gun. But his voice was his major weapon. At least that’s the image conjured by the dramatic account of a First-Class passenger who was present at the last gasp. Seventeen-year-old Jack Thayer saw an armed McElroy attempting to quell panic at the last. His account was written privately for friends and family in 1940, more than a quarter of a century after the disaster. Then a mature 45, but with imperfect recall, Thayer wrote:

There was some disturbance in loading the last two forward starboard boats. A large crowd of men was pressing to get into them. No women were around as far as I could see. I saw Ismay, who had been assisting in the loading of the last boat, push his way into it. It was really every man for himself …

Purser H. W. McElroy, as brave and as fine a man as ever lived, was standing up in the next to last boat, loading it. Two men, I think they were dining room stewards, dropped into the boat from the deck above. As they jumped, he fired twice in the air. I do not believe they were hit, but they were quickly thrown out.

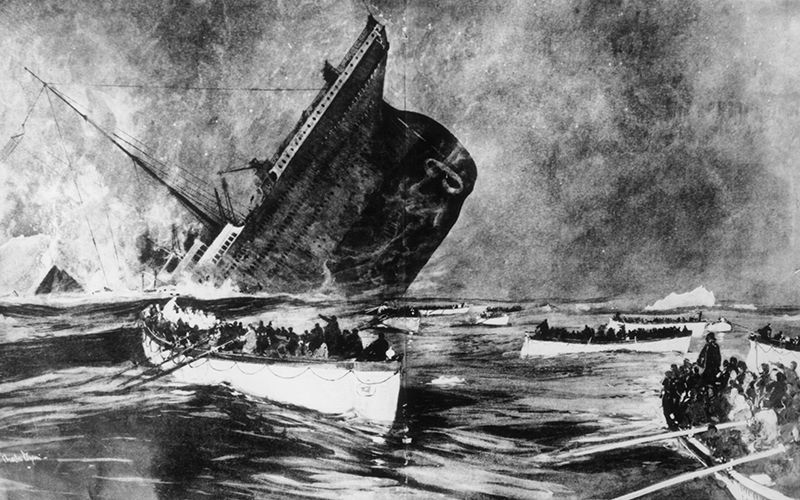

An illustration of the Titanic sinking while survivors rescue.

At some time there had been a lull in all this frenetic activity on the Titanic’s boat deck. McElroy found himself with Dr. O’Loughlin and other senior colleagues near the First-Class entrance. They shook hands, and then McElroy turned for a final handshake with others – Assistant Purser Reginald Barker was certainly there, and probably Assistant Purser Ernest Waldron King, a third Irishman in the group. Junior Surgeon John Simpson, yet another Hibernian, shook hands with the senior medic and the rest. They were saying to one another, ‘Goodbye, old man.’

Second Officer Charles Lightoller broke off his duties for a moment to also come over. He too grasped hands with everyone and wished them all the best. They were, after all, all in the same boat. And it was sinking beneath them. Within minutes, the waves came.

McELROY – April 14th, on board R.M.S. Titanic, Hugh, beloved husband of Barbara McElroy, Springwood, Wexford.

(Wicklow People, May 25, 1912)

Hugh McElroy’s family were originally from County Wexford and were staunchly Catholic. His parents had immigrated to Liverpool, where Hugh was born, like so many other Irish who went in search of work during the late nineteenth century when Merseyside was an engine of empire and the colonial trade. McElroy opted for a life at sea and served three years on the troopship Britannic during the Boer War at the beginning of the new century. He had thirteen years with the White Star Line, serving on the Majestic and Olympic before transferring to the Titanic. In 1910 he married his long-time sweetheart, Barbara Mary Ennis, whom he had known growing up in Liverpool. She was the daughter of John J. Ennis, the passenger manager of the Allan Line of steamships in that city. The couple made their home in Tullacanna, Harperstown, County Wexford when J. J. Ennis retired to his extensive family farm there. Barbara and Hugh were less than two years married when the Titanic sank, and had no children.

The Cork Examiner reported on April 18, 1912:

Mr. McElroy, the Chief Purser, was a Wexford man, and as fine a type as could be found. He was the Commodore Purser and only recently married the daughter of Captain Ennis of Wexford.

Mr. John J. Ennis JP … came to reside with his two daughters at his home place in

Springwood (Ballymitty, County Wexford). Last year, one of his daughters, Miss Barbara Ennis, was married to Mr. Hugh McElroy, who belongs to a very good Liverpool family, and is the brother to Fr McElroy, who lives close to Bootle. He had been a purser in the White Star Line for a quarter of a century.

The remains of the Chief Purser were destined to be recovered from the ocean by the MacKay-Bennett search vessel. He was wearing a white dress uniform – leading to the initial mistaken conclusion that it could be the body of a steward. From a fragment, they came up with the name of D. Lily, but in fact, there was no one of this name on board. The body was that of Hugh McElroy.

No. 157. Male. Estimated age, 32. Dark Hair.

Clothing – Ship’s uniform; white jacket; ship keys; 10 pence; 50 cents; fountain pen.

Steward. Name – D. Lily.

The body was buried at sea. A scrap of paper in the name of his wife was also taken from the remains and later provided corroboration of his identity.

Percy Mitchell, the White Star Line’s manager in Montreal, later signed a declaration to obtain the above effects from the coroner’s office of Halifax, Nova Scotia. He certified the name of the deceased as H. McElroy, Purser, SS Titanic, his residence as Southampton, England, his religion as Roman Catholic, and his nationality as Irish. The official name of the claimant, issued in the space provided, was ‘White Star Line’. It was perhaps appropriate. His white-clad corpse was the most senior member of the crew to be recovered, and he had been one of their brightest lights for a long time, ever the embodiment of the White Star Line.

Dr. J. C. H. Beaumont, for many years senior surgeon on the Olympic, claimed in his book "Ships and People," published in 1927, that it was known that Purser McElroy had premonitions about the new liner prior to embarkation. He did not expand on the remark.

1911 census – ‘Springwood’, Tullacanna, County Wexford.

John Ennis (75), a widower, retired steamship manager … Hugh Walter McElroy (36), purser. Wife Barbara Mary (34). Married less than one year.

Six servants, including domestics, farmhands, a stableman and professional nurse.

First-class house with ten rooms and 15 outlying farm buildings.

“The Irish Aboard the Titanic” by Senan Molony is available online.

* Originally published in 2012. Last updated in April 2024.

Comments