Tom Kettle died during the 16th Irish Division's assault on Ginchy, France during World War I

A few years back, I read a short biography about the mostly forgotten Irish Nationalist Tom Kettle. I was interested to read about him after I learned that he was a Nationalist MP who had died in the Battle of the Somme on September 9, 1916. I found his name on the monument at Thiepval.

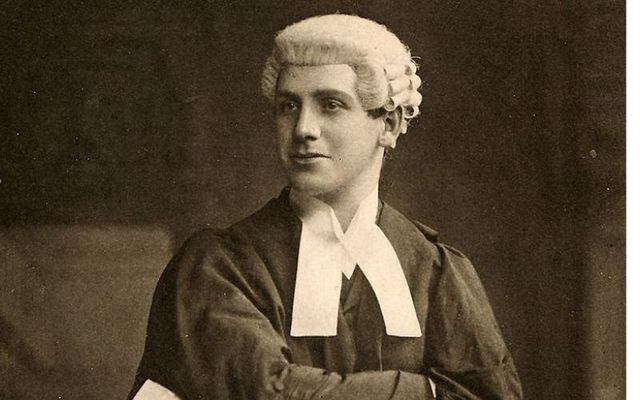

I'm not even going to try to summarize Kettle's life here. Not much anyway. He was an economist, journalist, barrister, writer, poet, soldier, and Home Rule politician, born in Artane, Dublin. He joined the Irish Volunteers in 1913, and then in 1914, enlisted with an Irish regiment to fight in WWI. He was killed during the 16th Irish Division's assault on Ginchy, France when he was 36 years old.

Before his unfortunate end, Kettle was a key figure in Dublin, a city that was the center of a budding national revival. The Irish language revival movement was flourishing in Dublin. The Gaelic Athletic Association was flourishing in Dublin. Of course, there was a literary revival led by Yeats, Synge, Lady Gregory, George Russell (AE), and others.

And there was a political revival going on as well, with the Irish Home Rule Party bouncing back after the battering it took following the fall of Charles Stewart Parnell in 1890. In addition, Sinn Féin was born at this time and its founder Arthur Griffith was also making a name for himself and his movement. Eamon De Valera had just eased onto the stage at this stage. A little later, Padraig Pearse and other future leaders of the Easter Rising began to make their mark.

Dublin in the early years of the 20th century was an amazing city, an exciting city. Kettle was in the middle of all of those movements. He was younger than Yeats and Lady Gregory, but he knew them — even if only at something of a distance. And they knew him. Kettle knew better those who were his own age, friends of his from college. Oliver St. John Gogarty, Padraic Colum, Francis Skeffington, and others who made names for themselves in 20th-century Ireland.

Kettle also knew James Joyce and Joyce's younger brother Stanislaus. Joyce flits in and out of the Kettle biography, but I can see why he chose Dublin in 1904 for his masterpiece. The place was a bubbling cauldron of political intrigue and artistic — mostly literary — experiment and endeavor.

Kettle's wife Mary and her sister Hannah, who later married Francis Skeffington, led Ireland's suffragette movement.

Kettle was a leading nationalist, an MP for the Irish Home Rule Party, but with more of a nationalist edge than the party's leader John Redmond. He once shared a platform with aging Fenian, O'Donovan Rossa, in New York.

Kettle packed off the weapons for Dublin and donned his journalist's hat and started filing war reports. He was horrified by what he witnessed, considered the German assault on Belgium an attack on civilization. He became convinced that Irish nationalists had to stand with the Belgians. It would cost him his life and, maybe worse, his place in Irish history.

When Kettle returned to Ireland, he acted as a recruiting agent for the British Army. Kettle, as much as anyone, convinced 90% of the Irish Volunteers and countless other young, impressionable Nationalists to enlist.

His commitment to Belgium's cause wasn't shared by every Nationalist and when the Easter Rising took place, Kettle knew his place in history was assured: the rebels would be the heroes and he'd be just another British officer. He was right.

When the war ended, the cause of Irish freedom got a new spark. Some of those who had followed Kettle into the British Army now signed up with the Irish Republicans and helped found a new Ireland, one that had no place for Tom Kettle in the national memory. Today this giant of pre-WWI Nationalist Ireland is barely acknowledged and hardly remembered.

Kettle's poem, written days before his death:

To My Daughter Betty, The Gift of God"

In wiser days, my darling rosebud, blown

To beauty proud as was your mother’s prime,

In that desired, delayed, incredible time,

You’ll ask why I abandoned you, my own,

And the dear heart that was your baby throne,

To dice with death. And oh! they’ll give you rhyme

And reason: some will call the thing sublime,

And some decry it in a knowing tone.

So here, while the mad guns curse overhead,

And tired men sigh with mud for couch and floor,

Know that we fools, now with the foolish dead,

Died not for flag, nor King, nor Emperor –

But for a dream, born in a herdsman’s shed,

And for the secret Scripture of the poor.

Comments