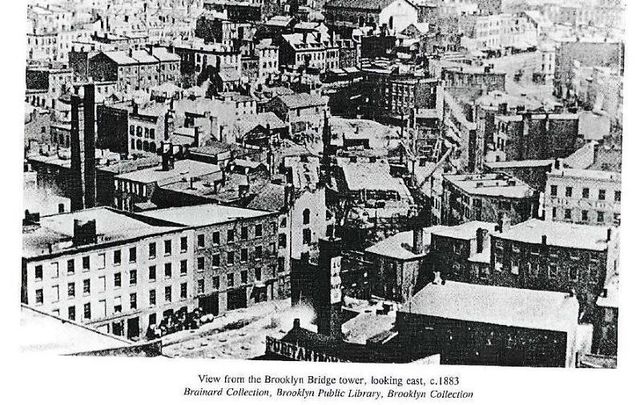

The Famine Irish settled along the Brooklyn waterfront neighborhoods in large numbers after the Great Hunger and continued pouring in throughout the late 1800s. From Greenpoint to the Gowanus Canal, Brooklyn wards were filled with families looking for regular work and the piers and docks where the ships let off provided the best opportunity.

The people of Irishtown were a gritty, hard-working lot employed by the shipbuilders of the local Brooklyn Navy Yard and the gas works companies. They were longshoremen, firemen or factory workers and filled the ranks of what became known as the Fighting 69th, New York Infantry of Thomas Meagher’s Irish Brigade during the American Civil War.

The residents of Irishtown became known for their distinct Irish spirit – and spirits.

Long before Prohibition in the 1920s, Brooklyn’s Irishtown was famous for its homemade, illegal whiskey distilleries and the battles pitched to defend them.

“Whiskey was the prevailing beverage down there, and water was mainly used to wash with,” said a resident.

Secrecy was what made Brooklyn’s Irishtown different than Manhattan’s Five Points. All the same things happened in Irishtown that happened in Manhattan’s infamous neighborhood (portrayed in “Gangs of New York"), but Irishtown kept its secrets.

As the famous bank robber Willie Sutton (born on Nassau and Gold streets in Irishtown) once quipped, “a code of silence was observed in Irishtown more faithfully than omertà is observed by the Mafia... Nobody ever talked in Irishtown.”

It was a separated society, similar to a commune, that violently closed itself off and refused the influence of Anglo-America. The people of Irishtown provided their own policing measures when someone got out of line, which was inevitable in such a rollicking neighborhood. The numerous gangs were the ones that maintained order as the local authorities and courts were largely ignored.

Inevitably though, there would be a showdown between the street corner “bucks” in Irishtown and the American notion of law and order. Similar to what brought Al Capone down much later, the U.S. government would confront Irishtown over alcohol and taxes.

Distilleries were honeycombed throughout Irishtown, hidden in tenement basements and rooms. But what made them illegal was the fact that Uncle Sam didn’t get to dip his finger into the profits.

According to lore from local bards, revenue officers supported by the police “invaded” the neighborhood to overturn the stills, but were harassed and their blackjacks were no match for the great number of loyal Irishtown residents who had no interest in allowing outsiders to tell them what they could and could not do.

Love Irish history? Share your favorite stories with other history buffs in the IrishCentral History Facebook group.

Inevitably, a few barrels were dumped in the East River, but gangs fought them deftly. Mothers shamed them away, and at the end of it Irishtown distillers used their political connections to remedy the problems the police and revenue officers created.

Newspaper articles from the time note that when a police officer “made himself obnoxious, his transfer to some other district was easily secured.”

But more telling are the many stories of police and revenue officers having an open-handed policy toward the distillers; an “open hand” as in they accepted bribes and were allowed a portion of the distillers’ profits in exchange for keeping the Irishtown “raids” controlled or giving a notice in advance. And it was certainly true that after these raids, “the illicit product would go on as merrily as if a still... had never been seized.”

The Irishtown distillers, in fact, were a boastful, blaguarding lot. Fellows like “Ginger” Farrell, “Ned” Brady and John Devlin were “men of robust physique, bluff manners and iron determination.”

Using Irishtown’s built-in defenses, these men made great profits without having to pay tribute to the government.

As one paper wrote, “The margin of remuneration was wide enough to lead the illicit distillers to take desperate chances in preparing and disposing of their fraudulent fluid.”

But for The Gas Drip Bard, an Irishtown native storyteller of “dear old Irishtown,” the distillers were famous for other reasons. These Irishmen, who had come from extreme poverty, suffering, and even, some say, genocide, suddenly become rich beyond their dreams. Prancing around the neighborhoods “gaudily tinseled” they gave orders to all the paupers like the gypsy-kings of Kings County they were and “had wild, barbaric notions of what constituted real luxury.”

This article was originally published in Ireland of the Welcomes magazine. Subscribe now!

This black market Irishtown economy had no shortage of comical double-dealers and swindlers. One story tells of a miscreant jeweler named Grady who seemed to rise above them all, dubbed “purveyor of ornaments.”

According to a resident, Grady had “by his sly machinations bled each of (the distillers) of a small fortune” by selling them stolen merchandise such as headlight-sized diamond studs and large gold watches with gold chains “long enough to hang a ten-year-old boy by the heels.”

Irishtown was by no means a wealthy neighborhood, but it had its own stories and drank its own “sweet poteen.” The neighborhood was held together by its own ruffian gangs that patrolled the streets and were connected to the right people with their own rogue businessmen who paid outsiders to stay away.

Then came the decorated Brooklynite and Anglo-American politician Silas B. Dutcher. On December 3, 1873, under Dutcher’s command “as the snow was falling fast,” the United States Marines, reinforced by the revenue officers and police all marched out of the Navy Yard with bayonets fixed to their guns. The Siege Of Irishtown was underway.

The Velvet Caps of Irishtown, a gang that was headquartered on the Little Street docks, sprung to action and fought valiantly. People took to the clapboard and tenement rooftops with their “Irish confetti,” throwing “dornicks” (rocks), paving stones, chimney bricks and from kitchen windows women threw streetwise their “kitchen utensils... gyrating through the air.”

A great battle ensued, but the soldiers had ten-day rations and held fast. Although illegal stills and gangs didn’t completely disappear, the old days of Irishtown’s insular, Celtic civilization began to wear away, particularly so after the immigration of so many other ethnic groups into the area.

Unlike Five Points, Irishtown stayed powerful, if not insularly powerful, up until Prohibition. During this time, however, the New York Harbor and its great shipping industry was slowly giving way to new methods of transportation, and so went the people of Irishtown, who found new jobs and moved up and out. To New Jersey, Long Island, upstate or Connecticut and eventually Florida they went, as the great exodus from America’s cities to the suburbs had begun.

But also unlike Five Points, the story of Irishtown is little-known today. Ultimately, what kept the old Irish ways in Irishtown alive for so much longer than Five Points, was also what kept its reputation out of the limelight. The Code of Silence may have kept the police and others out during Irishtown’s heyday, but in the long run it also left historians without much to speak of.

---

Eamon Loingsigh is the author of Light of the Diddicoy, the first book in the Auld Irishtown trilogy. The second book is due out March, 2016 via Three Rooms Press. Read more of his writing on his blog, artofneed.

* Originally published in December 2014, updated in May 2023.

Comments