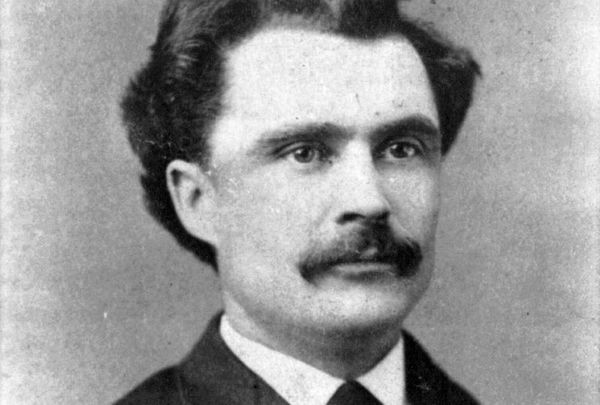

Was John Boyle O'Reilly the greatest Irish American of all? The Irish poet, journalist, author, and activist was born on June 28, 1844 in Meath. In 1870 he arrived in Boston.

Editor's note: In this 2008 article, Richard J Sullivan, a proud Bostonian, a Navy fighter pilot veteran of the Korean war, and a valuable contributor to Tinteán magazine, explains where John Boyle O'Reilly sits in Ireland and the diaspora's history.

Growing up in the 1930s in the suburbs of Boston, the two most important male adults in my life were my father and my Uncle Tom. Both were first-generation Irish-American journalists, largely self-educated, self-assured, urbane, and successful.

Good friends, they enjoyed nothing more than relaxing, glass in hand, discussing a vast array of subjects, frequently accompanied by good-natured needling. However, on one subject there was an almost reverential unanimity – that no other person had done more for the cause of the Irish in America than John Boyle O’Reilly. I remember these occasions well.

Among those Australians and Americans who recognize the name John Boyle O’Reilly, the initial perceptions are likely to be different though both are valid. Australians will have the image of a recently transported young Irish patriot who staged a daring, successful escape from the Western Australian penal colony in 1869, the first man ever to do so.

Americans will recognize the talented poet, writer, and editor who waged a relentless campaign for the assimilation of Irish immigrants into American society in the late 19th century. O’Reilly cajoled new Irish immigrants into the benefits of ‘honest hard work for one year’ believing that this would assist the cause of Irish independence far more than ‘a lifetime of worthless conspiracy.’ At the same time, he railed against the systematic denial of basic opportunities and blatant discrimination such as “No Irish Need Apply” notations in job listings.

John Boyle O’Reilly was born in 1844 in Dowth Castle (near the port of Drogheda, Ireland) where his father was a mathematician and a school headmaster. Young John grew up a very healthy, robust, and active child, intently loyal and proud of his native Ireland. He listened to tales from his mother of her relatives who had been famous Irish rebels. Tutored by both his father and mother, he acquired a sound basic education as well as a great sensitivity to the long tragic history of his homeland.

At nineteen, he enlisted in the British Army (60 percent of the 26,000 troops in Ireland were Irish). Already a member of the Fenian movement, a part of the Irish Brotherhood, O’Reilly set about recruiting additional members. When his actions were uncovered by British authorities, he was charged with insurrection, court-martialed and convicted. Probably because of his youth – he was only 21 – his death sentence was reduced to twenty years penal servitude. Twenty months later, he was transported to Western Australia.

Love Irish history? Share your favorite stories with other history buffs in the IrishCentral History Facebook group.

Upon arrival at Fremantle Prison, the first thing he did was set about plotting an escape. Cautioned, but later vitally assisted by Father Patrick McCabe, an escape was finally effected on an American whaling ship, The Gazelle. The journey was filled with close calls and two changes of ships before he finally arrived in Philadelphia, just two years after his transportation.

O’Reilly did not linger in Philadelphia but moved on to New York City. There he spent one month before traveling to Boston where he would make his home for the rest of his life. His path in the States was eased by the many Irish organizations who knew of the young man’s history – anyone who could create such embarrassment for the British Empire at the height of its imperial powers was going to be well received. Boston was a favored destination for Irish immigrants.

It already had a significantly large Irish population, so large that strains between the Catholic Irish and the largely Protestant establishment were growing constantly. What was needed was a balanced and moderating voice capable of tempering the extremes of both sides.

He obtained employment as a reporter for The Pilot, a newspaper catering primarily to the interests of Catholics.

O’Reilly accurately reported the poor planning and the ineptness of the Fenians as a fighting force. His coverage gained The Pilot and himself wide acclaim and propelled his career. Within the year, he was made The Pilot’s editor. The Fenian cause was a diminishing force whose public acceptance was waning steadily.

O’Reilly began to adopt an outlook that emphasized less outright violence but more a political opposition, later championed by Charles Stewart Parnell. O’Reilly never outrightly repudiated his Fenian friends. He drifted towards a more thoughtful and restrained form of opposition typified by the 20th-century leaders, Gandhi, and Martin Luther King.

O’Reilly used The Pilot to broaden his concern about the injustices suffered by not only the Irish but also the Jews, Native Americans, and African Americans. He also disparaged the harsh treatment of labor during America’s Industrial Revolution in a period of accelerating expansion.

Meanwhile, O’Reilly’s personal conditions changed when he married Mary Murphy in 1872. Early in their marriage, Mary wrote a children’s column in The Pilot. They had four daughters and, by all accounts, O’Reilly was a doting father and it was a very happy family.

O’Reilly stayed very well informed about events in Ireland during this period. He published detailed appraisals of these along with his own views in The Pilot. He endorsed the Land League and Home Rule movements fully but his endorsement became more restrained with the advent of the 'no rent' manifesto. He saw in the manifesto the potential for injustices and he was uncomfortable with its radical tone.

Charles Stewart Parnell, a Protestant Irish landowner, arrived in the States in 1880. O’Reilly supported this ardent advocate for the cause of Home Rule in Ireland in the British Parliament. Throughout his political career, Parnell’s disruptive tactics in the British Parliament had made him a thorn in the side of the British government, to the extent that they imprisoned him briefly in 1880-81. Sadly, the censure of the Catholic Church in Ireland for his long affair with a married woman, Kitty O’Shea, brought about his political downfall.

O’Reilly was the joint initiator and intimately involved with planning for the great Catalpa mission of 1876. The Catalpa was purchased in New Bedford, about thirty miles outside of Boston. When the mission was successful and six Fenian prisoners had been snatched to freedom from the Western Australian penal colony, Irish spirits throughout the world were lifted immeasurably. The British were subjected to even greater public derision than in the aftermath of O’Reilly’s own escape.

O’Reilly never wavered nor deviated from his primary goal of a free Ireland. He felt that to accomplish that goal, achieving respect and acceptance for both the Irish and Catholicism in America were necessary. The Pilot regularly reminded its readers of their opportunities as well as their obligations in America and personal responsibility was demanded.

Moderation, tolerance, generosity, and charm were fundamental elements of O’Reilly’s character. No one was better suited to deal with the standoffish, cold, and ‘proper’ native Bostonians who retained many of the traits of their aptly named Puritan forebears. To their credit, they accepted the intensely Catholic O’Reilly’s efforts to eliminate obvious injustices and discrimination. Of course, none of these gentlemen welcomed the idea of becoming a target of stinging editorials in The Pilot, particularly since O’Reilly’s and The Pilot’s influence was increasingly nationwide.

The political scene in the US and its coverage in the paper quickly became O’Reilly’s particular fascination. He was an ardent Democrat which was always reflected in The Pilot. His evaluations of senior government appointments always depended on the appointee’s enthusiasm for the pursuit of freedom for Ireland and anything related to it. (O’Reilly’s level of influence was obvious when President Grover Cleveland met with him in New York to discuss the pros and cons of an extradition treaty with Britain that was then pending. O’Reilly opposed any treaty of any kind with Britain).

By 1890, Mary O’Reilly was very sickly and had become semi-invalid. Her husband was the opposite and remained an athletic man. He was well-traveled and in the spring of 1890, completed a transcontinental lecture tour. O’Reilly did, however, have a bad problem with insomnia, but had always managed to avoid a reliance on sleep-inducing drugs. On August 9, a Saturday night, sleep eluded him and he decided to try some of his wife’s medications. They became a lethal combination and he never woke up. Barely 46, John Boyle O’Reilly was dead.

Boston was badly shaken by the loss of the man who had done so much to shape the city for a better, more balanced future. Condolences poured in from around the world and eulogies were delivered from pulpits, lecture halls, the press, and even the British House of Commons. The Boston Herald, the city’s most conservative newspaper, wrote:

"He was a paladin of chivalry, sent down into our generation, except that he drew no credentials from palaces; his commission was always from the people. He had both mental and physical bravery to rank with either ancient or modern heroes."

Impressive memorials have been erected in Boston at an entrance to the Fenway, in Dowth, Ireland, where he was born, and in the Leschenault Peninsula Conservation Park near Bunbury, Western Australia, the launch point of his great escape.

The thousands of later immigrants who settled in Boston, whatever their country of origin, whatever their faith, followed a path significantly eased by O’Reilly’s efforts. Certainly, the Irish, be they in Ireland or the great Diaspora, can feel pride and be thankful for this magnificent man.

*Richard J Sullivan (29/06/1930 - 28/05/2010) "Dick" was a proud Bostonian, a Navy fighter pilot veteran of the Korean war, and a valuable contributor to Tinteán magazine.

Tinteán, December 2008, updated in August 2023.

Comments