Across the world there exists a vast continuum of recollection reflected in Ireland's Great Hunger art and story.

Margaret Kelleher, Chair of Anglo-Irish Literature and Drama at University College, Dublin addresses the challenge of how we choose to remember an event that has been called everything from an unfortunate tragedy to mass murder.

St. Patrick's Society Lecture 2108, Margaret Kelleher

As a prelude to her exploration of sites and social memories of the Irish Famine, the 13thAnnual St. Patrick’s Society Lecture, Dr. Kelleher, speaking to a packed room at Concordia University in Montreal, began with a memory of her own: a visit to Grosse Île Canadian Irish Memorial National Historic Site in 2006, accompanied by the late famine historian Marianna O’Gallagher.

After this visit, Marianna had presented Margaret with a copy of her book: Grosse Île: Gateway to Canada, with the inscription: “souvenir du’ne belle journée dans la presence de nos ancetres” – “a memento (or souvenir) of a beautiful day in the presence of our ancestors”. It was this inscription that prompted Dr. Kelleher “to reflect in a more explicitly personal register than hitherto on the familial dynamics of famine commemoration and social memory.”

These dynamics see families move in and out, across generations and on both sides of the Atlantic from Grosse Île to Macroom, County Cork as they live out the threads of the famine narrative, transmitting memories of famine events to create a “public memory”, giving voice to those whose voices might otherwise not be heard.

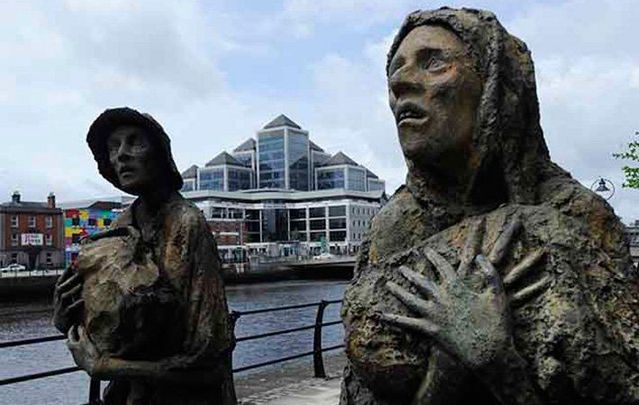

Delaney's Famine Memorial, Stephen's Green, Dublin

Dr. Kelleher then takes us on a journey to visit a number of Irish Famine monuments, from the abstract and controversial Delaney Monument, overshadowed by the statue of Theobald Wolfe Tone in St. Stephen’s Green in Dublin to Gillespie’s tableaux on the Dublin Custom House Quay, The Irish National Famine Monument in Murrisk County Mayo, the Children’s Strand in Carraroe, Co. Galway, Staten Island and the U.N. Plaza in New York, the Boston Freedom Walk and the Philadelphia Monument. She guides us to witness the differing famine narratives and spectrum of emotions: anger, fear, heartbreak, wretchedness, despair, and hope. She reminds us that, between genocide and benign neglect, there exists a vast continuum of recollection reflected in art and story.

An example of one controversy, provided by Kelleher, centers on the million-dollar Boston Famine Memorial that depicts a starving family transformed into strapping, vigorous figures on contact with America’s shores (one male figure appears even to sport a more than passing resemblance to JFK), which Irish critic, Fintan O’Toole called “a dreadful piece of kitsch” and “blithely optimistic images of a terrible catastrophe”. To which Michael Quinn of the Boston Famine Memorial responded that O’Toole revealed “an incomplete understanding the Irish-American perspective” and that “Irish-American history overlaps but does not mirror Irish history”. In another example, Dr. Kelleher provided a contrast to some of the grander monuments with the simple yet powerful memorial stone at Trá na bPáistí (the Children’s Beach) in Carraroe, Co. Galway in Connemara, a burial ground for unbaptized children.

Famine Memorial, Boston, Freedom Walk. Courtesy, Dr. Emily Mark-Fitzgerald/Irishfaminememorials.com.

Dr. Kelleher weaves her threads together connecting the Gallagher ancestral home in Macroom to the nearby recently rehabilitated famine cemetery, a mass grave in Carrigastyra and the tragic story of two parents, Pádraig and Cáit, who “escape the workhouse one night in order to visit the burial site where they lament their children’s death.” The fate of the parents is memorialized in the haunting poem by Eavan Boland, “Quarantine”:

In the worst hour of the worst season

of the worst year of a whole people

a man set out from the workhouse with his wife.

He was walking – they were both walking – north.

She was sick with famine fever and could not keep up.

He lifted her and put her on his back.

He walked like that west and west and north.

Until at nightfall under freezing stars they arrived.

In the morning they were both found dead.

Of cold. Of hunger. Of the toxins of a whole history.

But her feet were held against his breastbone.

The last heat of his flesh was his last gift to her.

Let no love poem ever come to this threshold.

There is no place here for the inexact

praise of the easy graces and sensuality of the body.

There is only time for this merciless inventory:

Their death together in the winter of 1847.

Also what they suffered. How they lived.

And what there is between a man and woman.

And in which darkness it can best be proved.

Children's Strand, Carraroe, Co. Galway, Ireland. Courtesy, Dr. Emily Mark-Fitzgerald/Irishfaminememorials.com.

Finally, Dr. Kelleher takes us to a social media image that superimposes the figure of an immigrant family on an image of Gillespie’s famine sculpture at Custom House Quay, that was in circulation after the death of Syrian toddler Alan Kurdi, reminding us of those that are included and excluded from memorialization and, as Dr. Kelleher quotes the words of Marianne Hirsch: “the capacity to respond to the needs of the past in the present”.

Image of three asylum seekers imposed on a photograph of the famine memorial on Custom House Quay in Dublin.

Margaret Kelleher is Professor and Chair of Anglo-Irish Literature and Drama at University College Dublin. Her books include The Feminization of Famine (published by Duke UP and Cork UP, 1997), The Cambridge History of Irish Literature (2006), co-edited with Philip O'Leary, and Ireland and Quebec: Interdisciplinary Essays on History, Culture, and Society (Four Courts Press, 2016), co-edited with Michael Kenneally. She has recently completed a monograph entitled Language, Life, and Death: Myles Joyce, James Joyce and the Maamtrasna Murders.

This article was submitted to the IrishCentral contributors network by a member of the global Irish community. To become an IrishCentral contributor click here.

Comments