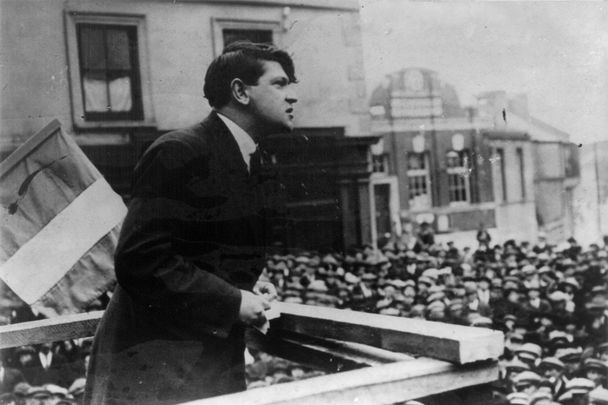

The most explosive date in Irish history is December 6, 1921—the date that Michael Collins signed the Anglo-Irish Treaty that created the modern Irish state.

On December 6, 1921, the Anglo-Irish Treaty was signed between Irish and British negotiators that determined the shape of 20th century Ireland. It is a date that should be celebrated, but it is a date that to this day hangs heavy over the Republic.

For although it banished the British from 26 counties of Ireland, it is a date that also marked the commencement of internal hostilities among Irish Republicans. The Irish got their nation, but they also got a Civil War—and nearly a century of accusations and recriminations.

This date also marks the end of one year and 16 days of turmoil. This explosive period began with Bloody Sunday 1920 and ended on December 6.

Here is a breakdown of this historic and tumultuous timeline that led to nationhood:

November 21, 1920 – it was on this date, known as “Bloody Sunday,” that Collins’ Squad, his Twelve Apostles, acting on information gathered from the intelligence office at 3 Crow Street, shot 14 British Secret Service agents in their beds. The savagery shocked the British into realizing that there was only one solution in Ireland and that was a negotiated peace.

Christmas 1920 – Eamon de Valera returned to Ireland after 20 months in America. He had three words for Collins and it wasn’t “Nollaig Shona Duit” (Merry Christmas). De Valera knew that because of Bloody Sunday, feelers from Downing Street were forthcoming and he wanted to get back into the game. He also wanted to show that there was more than one “Big Fellow” in Ireland.

In the following months, he would harass and hinder Collins’ guerrilla warfare, causing a stalemate between the British and Irish to last through the spring.

March-June 1921 – Collateral Damage. While the politicians procrastinated on their way to the conference table, ten young Irishmen were dropped at the end of a rope in Mountjoy Gaol. Today, they are known as “The Forgotten Ten,” but it really should be the “Forgotten Nine.” The first victim, Kevin Barry hanged on November 1, 1920, is a legend because of a famous song about him.

The other nine—Thomas Whelan, Patrick Moran, Patrick Doyle, Bernard Ryan, Thomas Bryan, Frank Flood, Thomas Traynor, Patrick Maher, and Edmund Foley—were hanged in March, April, and June. Some were “guilty” of their crimes, but others were not, as their lawyer, Mike Noyk, knew. This was another case of the British continuing their reign of terror on Ireland. With the truce coming about in July, these nine young men basically died for nothing—except British vindictiveness.

May 25, 1921 – the burning of the Custom House in Dublin. De Valera did not like the filthiness of Collins’ guerrilla warfare. He desired something much more pristine. He told IRA Chief-of-Staff Richard Mulcahy that he wanted “one good battle about once a month with about 500 men on each side.” [Note: de Valera didn’t mention if there would be a referee to make sure the British didn’t send in 501 men.]

After pestering Collins for months, de Valera got his wish when the IRA burnt out the Custom House. It was an utter disaster for the IRA and Collins’ Squad as 100 men of the Dublin Brigades were arrested. The British, mistaking stupidity for audacity and strength, though it showed the strength of the IRA, and, at the urging of King George V, there was soon a truce.

July 11, 1921 – the Truce takes effect. De Valera went to London with Arthur Griffith, not Michael Collins. He had one-on-one discussions with British Prime Minister David Lloyd George and was told point-blank he was not going to get a Republic and that part of Ulster would be partitioned. With heavy negotiations scheduled for the fall, de Valera refused to return to London.

October 11, 1921 – Collins reluctantly traveled to London. In fact, he arrived separately from the rest of the Irish delegation. He stayed in his own townhouse and brought his own staff, including many of his intelligence chiefs: Liam Tobin, Tom Cullen, and Ned Broy. Although he trusted Griffith, he was highly suspicious of Erskine Childers, secretary to the delegation, who he thought was either a de Valera spy, or a British spy—if not both.

He was aware that de Valera said, as he sent the plenipotentiaries off to London, “We must have scapegoats.” Collins, ever the realist, stood his ground: “Let them make a scapegoat or anything they wish of me. We have accepted the situation, as it is, and someone must go.” Tim Pat Coogan, a biographer of both Collins and de Valera, believes “It was the worst single decision of de Valera’s life, for himself and for Ireland.”

With Griffith’s health already deteriorating, Collins became the leader of the negotiations, often keeping the rest of the delegation, save Griffith, in the dark. He forged strong relationships with Winston Churchill and Lord Birkenhead, which would bode well when the new Irish Free State came into existence in early 1922.

December 6, 1921 – after weeks of intense negotiations between Collins, Griffith, Lloyd George, Churchill, and Birkenhead the Anglo-Irish Treaty was signed at 2:30 a.m. in the morning.

Churchill observed that “Michael Collins rose, looking as though he were going to shoot someone, preferably himself. In all my life, I have never seen so much pain and suffering in restraint.”

Lord Birkenhead, after he signed, sighed: “I may have signed my political death-warrant tonight.”

Collins shot back: “I have signed my actual death-warrant.”

He was right, he had less than nine months to live. But before his death, he would push the Treaty through the Dáil, get the Irish people to overwhelmingly ratify it in a referendum on June 16, 1922, and begin making inroads against the anti-Treaty forces while leaving hopes of a negotiated settlement possible. But his death would change all that and a brutal civil war ensued which fractured Irish society for the rest of the century.

Read more

De Valera After Collins and the Treaty

Within a decade de Valera was back in power and Collins, “the man who won the war”—as Arthur Griffith famously said in the Dáil during the Treaty debate—faded from the national memory. But he did not fade from the memory of Eamon de Valera. Collins' grave in Glasnevin Cemetery in Dublin stood without a marker for 17 years until de Valera granted permission in 1939.

There were all kinds of restrictions on the marker, as Coogan points out in his biography of Collins, and the final insult was that at the unveiling of the stone no press or public celebration was allowed—only Collins’ brother Johnny was allowed to attend. It was as if de Valera was still terrified of the Fenian ghost of the dead Michael Collins.

Did de Valera feel guilty for not going to London to do the heavy lifting in 1921? Was he haunted by the memory of the very dead but still very colorful Collins, the flamboyant Dublin Pimpernel?

It’s hard to say. De Valera had little to say about Collins the rest of his life, but about a decade before his death, he said this about his erstwhile antagonist: “It is my considered opinion that in the fullness of time history will record the greatness of Michael Collins and it will be recorded at my expense.”

For once, Dev got it right.

*Dermot McEvoy is the author of "The 13th Apostle: A Novel of a Dublin Family, Michael Collins, and the Irish Uprising" and "Our Lady of Greenwich Village," now available in paperback from Skyhorse Publishing. He may be reached at [email protected]. Follow him on his website and Facebook page.

Love Irish history? Share your favorite stories with other history buffs in the IrishCentral History Facebook group.

Comments