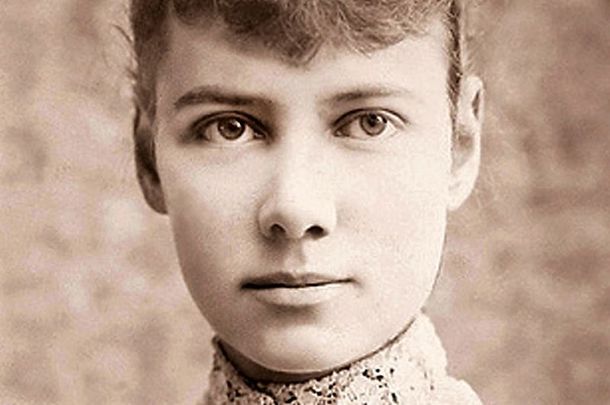

Irish American Nellie Bly was a pioneering investigative journalist not afraid to go to extraordinary lengths to reveal injustice and expose the abuses of 19th-century institutions.

Nellie Bly was born on May 5, 1864, as Elizabeth Jane Cochran in Pennsylvania, in Cochran’s Mill, a small township named for her family. Her grandfather, Robert Cochran, had left Derry for the US in the 1790s. Her father, Michael Cochran, who rose to prominence as a member of the judiciary, died when she was only six years old. Her mother moved the family to Pittsburgh in 1880.

Bly found her calling at an early age after responding to a column entitled “What Girls Are Good For” in the Pittsburgh Dispatch, which reported that girls were for birthing children and keeping house. She wrote a passionate response under the pseudonym “Lonely Orphan Girl” and sent it to the paper.

Pittsburgh Dispatch editor George Madden was so impressed with her response that he ran an advertisement asking the author to identify herself.

She went on to serve a brief apprenticeship with the newspaper, where she took the pen name Nellie Bly. One of her first pieces was on how divorce affected women. She also wrote a series of investigative articles on women factory workers, but after the newspaper received complaints from factory owners about her writing, she was assigned to the women’s pages to cover fashion and society.

She would later spend six months as a special correspondent in Mexico, where she protested the imprisonment of a local journalist and had to flee the country for criticizing the government.

Nellie Bly in Mexico (Public Domain)

She later left the Pittsburgh Dispatch and joined the staff of the New York World, where she would remain for the next eleven years.

Joseph Pulitzer, the owner and manager of the newspaper, encouraged her to focus on sensationalist stories and Bly would oblige, pushing boundaries to uncover stories that would give voice to the poor and socially disadvantaged.

For her first major scoop, she feigned madness to gain admission to the Blackwell's Island Women’s Lunatic Asylum. She stayed there for ten days to expose the mistreatment and abuse of the asylum’s patients.

“They inject so much morphine and chloral that the patients are made crazy. I have seen the patients’ wild for water from the effect of the drugs, and the nurses would refuse it to them. I have heard women beg for a whole night for one drop and it was not given to them. I myself cried for water until my mouth was so parched and dry that I could not speak.”

Her report, which was later published as a book "Ten Days in a Mad-House," highlighted the malpractices of Blackwell and led to a grand jury investigation and prompted reform. Bly, who would continue to expose abuses in the city’s institutions, usually undercover, became a minor celebrity.

Nellie Bly, in a publicity photo for her around-the-world voyage. (New York Public Library / Public Domain)

In 1889, Bly attempted to circumnavigate the glove and break the fictitious record of Phileas Fogg, the character in Jules Verne’s "Around the World in Eighty Days." The adventure soon became a competition, as reporter Elizabeth Bisland from the Cosmopolitan set out in the opposite direction in the hopes of beating Bly.

The expedition captured the world’s imagination. The New York World ran daily updates on her journey, which started at 9:40 am on November 14, 1889, and took Bly through Great Britain, France, Italy, Egypt, Sri Lanka, Malaysia, Singapore, China, and Japan.

She landed in San Francisco two days behind schedule as a result of rough weather on her Pacific crossing; however, Pulitzer arranged for a chartered train to take her to Chicago. She arrived in New Jersey on January 25, 1890, to huge, welcoming crowds.

Her record-breaking journey took 72 days, 6 hours, 11 minutes, and 14 seconds. Bly wrote about her journey in the "Around the World in 72 Days," which became a bestseller.

Bly beat her rival, who had missed her steamship from Southampton and arrived less than four days after Bly.

In 1895, at the age of 31, Bly married 73-year-old millionaire manufacturer Robert Seaman. She retired from journalism due to her husband’s failing health. Her husband died in 1904 leaving her in control of his Iron Clad Manufacturing Co., which made steel containers. Bly would go on to patent several inventions.

She later returned to journalism, covering World War I, and continued to highlight women’s issues.

Nellie Bly, representing the New York Evening Journal, speaks with an officer of the Austrian Army in Poland circa 1914. (International News Service / Public Domain)

In 1922, Bly died of pneumonia at the age of 57. She was buried at Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx. Seven years later, her one time rival, Elizabeth Bisland, also died of pneumonia and was buried in the same cemetery.

*Originally published in 2018. Updated in 2021.

Comments