In 2019, an exhibition at the Little Museum of Dublin compared the experiences of Irish Famine victims and refugees today, who seek protection in Ireland.

Part of the exhibit was "Leave to Remain," the account of a young Irishman on a coffin ship bound for Quebec in 1847, in words written by the Irish novelist Sebastian Barry.

This is the text:

The sad truth of hard times is there are few heroes.

It was our own people knocked our cabin. The Peelers that came with them up the valley were Dublin boys.

The landlord never made an appearance at all for he did not need to. He could get anyone he liked to do anything he liked because he had the pennies and they did not.

Looking back it seems to me that you will never save a starving people with committees and yet that is what was attempted.

The committee to do this and the committee to do that and then the people dying in the margins between. The poorhouse in Westport so full to the brim that only death made room for more entrants.

The feverhouse behind the great building a factory of suffering and hopelessness. It is hard to look back and tell what was to be seen.

My father came in from the valley when his place was knocked and went into Louisburgh because he was told the Poor Law Guardians would be there and he could ask for a ticket.

The little town of Louisburgh was also full to bursting like it was a fair day but it wasn’t for a fair day. Then the desolate crowd was told that the Guardians had gone up to Delphi Lodge in their side-car and my father would be obliged to follow after.

Up we went my father and ourselves with about three hundred others to see the Guardians. You might not know that district and it is all mountains and cold valleys and rivers as black as dried blood.

Way up the head of the mountains is a fine house called Delphi Lodge. That’s where the gentlemen were having their lunch. We waited out on the lawns in front of the house while they ate.

I won’t even say when was the last time any of us saw food.

The truth is my father was ashamed of our emergency and all the long traipse he never spoke a word. He was a proud man in his way that had worked his quarter acre like a Trojan for long hard years. At length the Guardians came forth and bid us return to Louisburgh and clear off the lawns because the tickets for the poorhouse were below. We had come many miles to hear that.

So with great and strange sighing the whole body of emaciated people turned from the cold windows and back we went the way we had come. Snow and its sister icy rain lashed against us and many started to fall, weak as they were.

Mothers went down and children and then even my father stumbled and down he went. He went down like a shot dog and never to rise. I went on with my brother Jamie following the buffeted crowd and by some strange grace we got back to Louisburgh.

The next day we got our tickets for Westport. It was a seven-hour walk across the mountains and by exactly the same narrow track we had come.

The sun because it has no sense of occasion had risen clear and bright as it sometimes does in an Irish autumn and all along the way we saw little humps of people, women with their long ruined faces, and babies and children frozen and starved to death.

A glaze of frost threw its fancy lace across their limbs. We passed them as if we were beings of another world called the living.

Out past Delphi Lodge the country became so desolate God Himself had never visited. It had neither character nor location but seemed merely a blank district of nowhere. Jamie and myself went on and even our hardened feet began to swell and crack.

We came down into Westport and proceeded to the poorhouse but though we had tickets they were useless. In front of the poorhouse was a crowd so immense they made a music like a lamentation of the mad.

By some instinct, I cannot identify I brought Jamie to the quay and when night fell we crept onto one of the old ships that we hoped would carry us away.

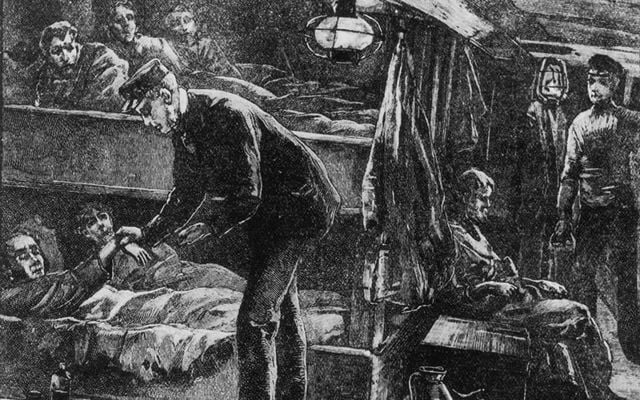

There were men selling passage on the ship. We had no money so I judged it would be beneficent to stow away. Now you will realise that we had stowed away on Hell’s cargo vessel. The passengers numbered about three hundred on a boat designed for at the most a hundred. It had maybe forty berths.

The people were obliged to bring on whatever provisions they could muster because the master had no food stowed for them.

Water was to be two cups a day and it seemed like water taken from a black drain. The hatches were locked and never to be opened and so began four weeks of filth, destitution, misery and death.

There are no gods and no priests for such a people. We were nothing and so nothing needed to be done for us. The hold remained closed and pitch-black and storms were only to be endured.

Empty bellies vomited the last froth of life and we shat and pissed where we lay. The bilges rolled with every type of human liquid. The air was air that could only have pleased Beelzebub.

All around me people died in a simple conclusion of calamity. Efforts were made in the dark to eat whatever was to be eaten. The abysm of suffering reached has not been described in human history because it would disgust and repel any reader.

No camera could capture it because it all took place in utter darkness as if we were already deceased and we were being punished for terrible sins.

Our sin was that we were too many in the eyes of the government and that it would be a blessing on the country if we were to perish.

In this way, we were described as a plague on our country and nothing more than vermin and rats.

Now a sensible and resourceful God was visiting destruction on us to rid the world of a colossal nuisance.

Will I tell you that Jamie died beside me, a boy of some seven years? I felt for his body in the darkness and touched his cold form.

His body was lying in a shallow lake of filth. That was his burial place, the dark hold of history.

When up we came into the waters by Quebec and the long nails were pulled from the boards of the hatches and light came into the hold like a pour of water.

Bleak eyes reflected it like fireflies in some adamantine region. What had been women stared out as if their minds were cancelled. Men raised their skeletal forms and tried to stand.

Everywhere around me were corpses and corpses with the ship’s rats using them unimpeded.

These small black ministers scampered away into the deeper bilges at the flooding of the light.

A ladder was let down and the survivors were brought up onto the deck.

Sailors themselves had died of fevers caught from us and even the master himself was dead.

The ship’s owner had got his money and the brokers had made their profits and they cared neither for cargo nor crew.

Profit in such circumstances is surely on the highest spot on the tabulation of evil. On the list of deeds that cannot be forgiven in any court of man or god.

Quebec was in that time in a great terror about these famished nothings because all we had to offer this new place was a great clamour for assistance.

But we were calling out, it seemed to them, from a region of virulent fever and indeed contagion had already burned through the town and further out into the countryside as if demons were firing heather.

Their solution was to herd us into long wooden sheds. Pastors and women almost insane in their bravery came in to us where we lay on the hundreds of pallets. Efforts were made to feed us and yet many were now beyond the benefit of food. The bodies were carted off and let down into pits.

No place on earth it seemed could have wanted us and all behind were coming another thousand ships heaving with their melancholy freight.

We had made our desperate attempt to escape the pestilence of hunger but because we were nothing – nothing could be done for us.

Visit the Little Museum of Dublin at 15 St Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2.

*Originally published in 2019, updated in 2025.

Comments