New research has found that the Irish rebels of the Irish Revolutionary period were more likely to come from families that were most affected during the Great Irish Famine.

The study, entitled ‘The Deep Roots of Rebellion,' employed methodologies from the field of economics to measure the impact of the Great Irish Famine (1845-50) on future generations.

Economic historians, who analyzed 2.7 million historical data points, found that individuals whose families had suffered greatly during the Famine were more likely to become Irish rebels and revolt against British rule two generations later.

By combining climatic data and apolitical factors such as soil quality and wind direction with contemporary historical reports and Irish census records, the researchers measured how exposed Irish families were to the Famine and how likely individuals were to participate in rebellion two generations later.

The research furthers the understanding of how large radical historical events can explain social unrest generations later.

The research was conducted by Dr. Gaia Narciso, Director of the Centre for Economics, Policy and History, Department of Economics, Trinity, in collaboration with Dr. Battista Severgnini, Associate Professor, Copenhagen Business School and was recently published in a paper in the Journal of Development Economics.

“The wealth of historical data available in the 1911 Census and other historical records allowed us to measure how each family name in Ireland was exposed to the Great Famine. We investigate the distribution of surnames over space and time to track how rebellion animosity lingered over generations," said Dr. Narciso.

“The novel use of econometric methodologies in the analysis of these historical data allows us to stand back from individual historical narratives to better understand the long-term effects of the Great Irish Famine.

“We show that individuals whose families had been most affected by the Irish Famine were more likely to participate in the rebellion against British rule during the revolutionary period, over 70 years after the Famine.”

The research exemplifies the work being carried out in the newly established Centre for Economics, Policy and History, funded by the Higher Education Authority under the North-South program.

Based at Trinity and Queen’s University Belfast, the new Centre combines economics with history to answer historical questions about the long-run development of society.

Love Irish history? Share your favorite stories with other history buffs in the IrishCentral History Facebook group.

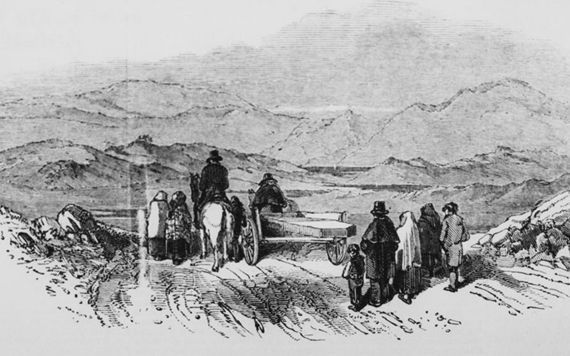

Dr. Severgnini added: “The Irish Famine, caused by potato blight, was one of the biggest tragedies of modern history, resulting in the death of 1 million people due to starvation and related diseases, and the emigration of a further 1 million people out of a population of 8.5 million people. Although the impact of the Great Irish Famine was immediate, historical evidence suggests that politically motivated rebellion smoldered under the surface for several years after.

“Social unrest and civil conflicts are usually studied ex-post, making it hard to disentangle the short and long-term factors that trigger an individual’s decision to rebel. This is the first study internationally that highlights the role of large adverse shocks in explaining social unrest in the long run."

The research was funded by Trinity through the Pathfinder program and the Arts and Social Sciences Benefactions Fund. It has also been supported by the Irish Research Council through its New Foundations scheme.

The full paper ‘The deep roots of rebellion’, Journal of Development Economics, Vol 160, can be read here.

Comments