On February 8, 1983, at the height of The Troubles, Ireland faced a truly mysterious crime that remains virtually unsolved.

Shergar, a beloved thoroughbred racehorse worth over $15 million, was kidnapped from his stable in Co Kildare by a gang of machine gun-wielding men in balaclavas. After failed attempts to demand money for the stallion, gentle Shergar was brutally killed and his body was never found.

The most famous and valuable racehorse in the world, Shergar had won the 1981 Epsom Derby by ten lengths, which is the longest winning margin in the race's 202-year history. Following this triumph, he had four more major derby wins and was named European Horse of the Year.

When he retired after that first season, racehorse owners paid up to $120,000 for shares in his services impregnating mares, eager to have young horses from his bloodline to train for races.

Read more

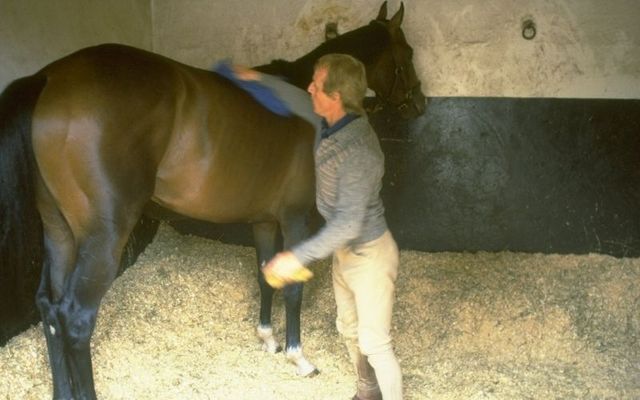

The stallion had a white blaze mark on his face, four white "socks" and a distinctive racing style of running with his tongue hanging out - he was gentle, calm and kind.

On the cold, muggy evening of February 8, 1983, Shergar was kidnapped by a gang of men in balaclavas, thought to be part of the IRA.

The bay colt was owned by the Aga Khan, the billionaire spiritual leader to 15 million Ismaili Muslims. When he was returned to Ireland after her first winning season, he was syndicated for $15 million between 34 people - each share was worth around $382,000, six of which were kept by the Aga Khan.

Shergar was just five years old when he was snatched in the middle of the night from the Ballymany Stud in Co. Kildare. He had been preparing for his second season as a breeding stallion, the BBC said.

It was shortly after 8 pm when the son of Jim Fitzgerald, Shergar’s head groom that lived at the stud, heard a knock at the door. He opened it to find two men wearing balaclavas wielding guns - one of them said, “We have come for Shergar. We want $3 million for him."

Jim Fitzgerald, a father of six, was forced at gunpoint to Shergar’s stable where they were joined by six more masked gunmen. He loaded Shergar into the horsebox the men had brought with them. Fitzgerald was then forced into their car at gunpoint.

Among others, one reason the investigation was so difficult for authorities was because the kidnappers had chosen the day before Ireland’s big Goff’s racehorse sale to abduct Shergar, when many horseboxes were being driven across all of Ireland’s roads, thereby making it hard to differentiate him.

"I can still remember that night in that car with them lads. All sorts of thoughts were racing through my head about what they might do to me. One of them, with the revolver, was very aggressive," Mr. Fitzgerald told the Telegraph about his ride in the kidnappers’ car.

After driving him around for three hours, the kidnappers dumped Fitzgerald out of the car. He found his way to a telephone and rang his brother - this phone call led to a series of phone calls between Shergars’ shareholders, his vet, racing associates and several Irish Ministers. This process is referred to as “a caricature of police bungling,” as the actual police weren’t notified until 8 hours after Shergar was taken and the men were long gone from the area.

Using coded phrases, the kidnappers soon began negotiations with a representative of the Aga Khan over the telephone but made sure to hang up before 90 seconds passed so that authorities couldn’t track their location.

Collectively it had been decided not to pay the ransom because they figured if they had, every racehorse in the world would be in danger, as many of them were worth over a million pounds (1.5 million dollars) and Ireland had lacked adequate security.

The hunt for Shergar created a huge media storm - everyone in the UK and Ireland were hell-bent on getting him back, and the Dublin police had offered an over $150,000 reward for his return.

The kidnappers had agreed to negotiate with a man named Derek Thompson who had worked for ITV’s racing team. He flew to Belfast to negotiate at the Europa Hotel.

He said the scene that greeted him at Belfast airport was unreal: "It was like being a film star. There were cameras all around." About 100 cameramen and journalists were in or outside the Europa Hotel as Thompson and his co-negotiators arrived.

The men never reached an agreement. Thompson received a phone call the next day from the kidnappers - they said, "The horse has had an accident. He's dead." He then hung up.

There are several ideas pertaining to what happened to Shergar. One idea is that the horse did have some sort of accident while in a frenzy, and the men killed him because they couldn’t handle his crazed manner.

Senior IRA leader Kevin Mallon is thought to be the man who devised the plot. A convicted killer from Co. Tyrone, he eventually became part of IRA folklore after shooting his way out of one prison and being lifted by helicopter from another.

What has been discovered almost definitively, according to a close course, was that two handlers, one clutching a machine gun, went into the remote stable where the horse was being held and opened fire.

A former IRA member told the Sunday Telegraph: "Shergar was machine-gunned to death. There was blood everywhere and the horse even slipped on his own blood. There was lots of cussing and swearing because the horse wouldn't die. It was a very bloody death." It was several minutes before Shergar bled to death.

It is also widely believed his kidnappers buried him in a bog in Co. Leitrim, though some think they dumped him into the sea of Ireland’s south coast.

Shergar's former jockey Walter Swinburn, who rode Shergar at his famous race, was distressed by the findings. "No horse deserves an ending like that - let alone one as special as Shergar.”

Shergar’s body was never found, and the case remains a mystery. The IRA has never officially claimed responsibility for stealing the beloved horse. The incident has inspired several books, documentaries, and a film starring Mickey Rourke.

* Originally published in 2015.

Comments