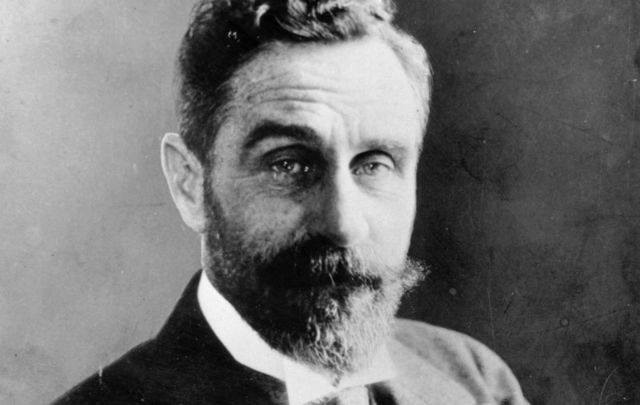

On June 29, 1916, Sir Roger Casement was found guilty of treason for his role in the Easter Rising and was sentenced to death by hanging.

Casement was the most prominent and intriguing figure involved in the Easter Rising. During three critical months in 1916, he kept the story of the Irish rebellion alive and came to personify the Rising and its portrayal in America.

As the first reports of the insurrection made their way across the Atlantic and appeared on April 25, 1916 (a day after Easter Monday, the day the Rising started), Sir Roger was the primary focus of attention. A headline on the front page of The Washington Post announced: “Capture Sir Roger in Irish Filibuster.” A smaller headline underneath ominously speculated: “Predict Death for Knight.”

On April 29, the Saturday of the rebels' surrender, The New York Times published 18—yes, 18—separate articles of varying length and approach about the Rising. An editorial and an essay of commentary concentrate directly on Casement.

Several news reports about Casement’s capture include the judgment “he is mentally unbalanced.” His psychological state receives examination so often someone today is forced to wonder why journalists kept raising the topic. Were British authorities whispering questions about Casement to make people wonder about him? Was the larger intention to sully the cause of Irish nationalism he championed?

Casement’s humanitarian work in Africa and South America for the British Foreign Service earned him a knighthood and prominence in the U.S. His elite status and confrontational stance against Britain proved irresistible to American editors.

For instance, the day after the surrender, The Boston Globe published a lengthy Sunday profile, “Sir Roger Casement’s Astounding Career,” and on May 14 The Washington Post ran an essay by Casement under the headline “England Seeking U.S. Aid to Dominate All Europe, Says Sir Roger Casement.”

On June 4, The Washington Post ran a mock conversation, offering a debate about Casement’s sanity. Headlined, “Madmen Make History: Sir Roger Casement Would Have Been Immortal If He Had Succeeded,” one of the fictional speaker's notes, “If America had not had at all times a sufficient supply of madmen on hand, it would not have become America.”

All the press attention towards Casement is critical to assess because he served at this historic moment as a human lightning rod for attracting American interest in the struggle for Irish independence.

The post-Rising executions of 14 rebels at Kilmainham Gaol took place between May 3-12. Casement’s trial in London didn’t begin until June 26, and, unlike the Dublin court-martials, the proceedings involving Sir Roger were public and extensively covered.

Kilmainham Gaol.

When someone tries to understand him in relation to the Rising, almost everything about Casement proves unique and complicated.

He’s arrested prior to the insurrection ostensibly on a mission to keep it from happening.

He’s taken to London for his trial.

He’s charged with treason for his actions in Germany rather than his involvement in the Rising.

He’s sentenced to hang instead of being shot—and his appeal results in even more attention.

Each particular about him is distinctive, yet in the eyes of Americans, he was lumped together with other rebels. That he was arriving in Ireland along with a shipment of German arms underscored the perception that Casement occupied a place as a ringleader at the center of revolutionary activities—even though the reality was different.

There’s a certain irony that American dollars bankrolled Casement’s nationalistic dreams. Prior to his arrival in New York on July 20, 1914—he stayed until October 15 that year—his opinions about the U.S. wouldn’t evoke Yankee endearment. “I don’t like the U.S.A.,” he wrote to a cousin in 1914. “The more I see of it the less I like it. The people are ignorant and unthinking and easily led by anything they read in their rotten papers.”

Despite these views, he understood the importance of the U.S. as an emerging world power. In early 1912, he met with President William Howard Taft in Washington, an indication of Casement’s clout, as well as recognition by the British of America’s place in the global community. Later, Casement began to see the Irish-American community as having the wherewithal to support the effort to achieve independence for Ireland.

Love Irish history? Share your favorite stories with other history buffs in the IrishCentral History Facebook group.

From Casement’s arrival in New York until his death, he was subsidized by American dollars. For three months—as the Great War began—he toured the U.S., raising funds to buy arms for the Irish Volunteers. Casement worked with members of Clan na Gael, the secretive American organization with direct ties to the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB), and particularly with Clan leader, John Devoy.

Both Casement and Devoy shared such boiling-point hatred of the British they conspired with Germany for assistance—a case of the enemy of my enemy becomes my friend.

Clan na Gael coffers supported Casement’s controversial trip to Germany, which began in October of 1914 and continued until his ill-fated return to Ireland prior to the Rising. At dinner on April 10, 1916, the night before he left Germany, Casement told a friend: “I feel that I am going to my end, but at least it is for Ireland!”

During the summer of 1916, Casement’s fate was a prime topic not only for the American press but also among government officials in Washington. The coverage of Casement—his capture, trial, appeal, and execution—kept him and his cause on Americans’ minds, and that attention, in turn, exerted pressure on the U.S. government.

Members of the House and Senate sought to help Casement by contacting President Woodrow Wilson. How the White House handled the case reveals a deliberate, if not strategic, duplicity that’s representative of the 28th president’s approach to Ireland and to Irish America.

Politically motivated lip service and feigned sincerity mask the policy reality of Wilson’s reluctance to get involved in what he considered an internal matter for the British.

A revealing gauge of American public opinion comes in reports of Cecil Spring-Rice, the U.K.’s ambassador in Washington. In his dispatches, Spring Rice keeps returning to the U.S. reaction to the events in Ireland, particularly their impact on Irish Americans. His observations gleaned from the press and staff reports, provide evidence of the change in American opinion—from questioning the Rising to favoring its objective—as it evolved.

Many of his unpublished dispatches are in the British National Archives at Kew, and those during this period amplify his judgments about the Rising and the executions, including Casement’s.

One particular message stands out. In a coded telegram dated August 1, Spring Rice reports he made an “informal verbal agreement” with Michael Francis Doyle, Casement’s U.S. lawyer, that neither would say anything about Casement’s scheduled hanging two days later. His last sentence refers to Doyle and provokes puzzlement: “He tells me privately that Clan Nagael [sic] want Casement executed.”

When so many American politicians and groups were working to save Casement, why Clan na Gael didn’t mind imposing the death sentence remains a mystery.

Despite thinking Casement should not become a martyr, Spring Rice circulated extracts from what are known as Casement’s “black diaries,” documenting multiple homosexual encounters. It’s now clear that Spring Rice deliberately wanted to blacken Casement’s name.

“Roger Casement is one of the most tragic figures in Irish history,” Devoy observed in his memoir, "Recollections of an Irish Rebel." Beyond that judgment, Casement’s human complexity and distinctiveness are as compelling now as they were a century ago.

*Robert Schmuhl is the Walter H. Annenberg-Edmund P. Joyce Chair in American Studies and Journalism at the University of Notre Dame and the author of "Ireland’s Exiled Children: America and the Easter Rising" (Oxford University Press). This article is abridged from his essay, “Roger Casement and America,” which appears in the April 2016 issue of Breac: A Digital Journal of Irish Studies.

*This article was originally published here in 2015. Updated in June 2024.

Comments