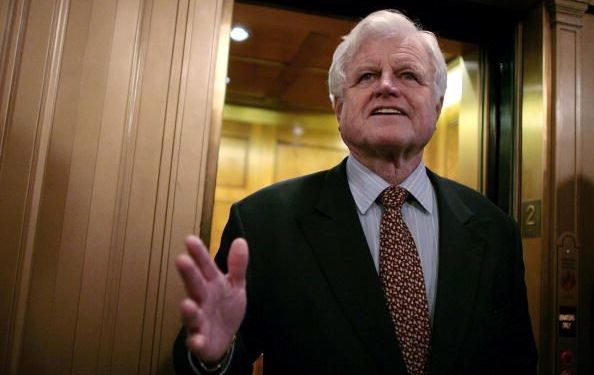

Of the four Kennedy brothers, Teddy was the only one who, in William Butler Yeats’ immortal words, lived to comb grey hair.

And boy, did Senator Edward Kennedy live a life, packing into his 77 years a massive volume of work, controversy, political genius, and a deep sense of caring for others despite his privileged background.

The new book, simply called "Ted Kennedy: A Life", by former Boston Globe White House correspondent John A. Farrell, synthesizes Kennedy’s many accomplishments, weaknesses, and all too visible humanity for good and bad in what will be a standard work for future biographers.

Consider that in his life alone, Kennedy lost his three brothers violently; one killed in an exploding plane during World War II, one gunned down as president, and the third assassinated as he campaigned for the presidency.

We should not be so judgmental about many of the mistakes Kennedy made in life. In addition to losing his brothers, he lost his nephew John Kennedy Junior and other younger family members.

His daughter Kara was diagnosed with lung cancer at the age of 42. His two other sons, Ted Junior and Patrick, also had issues – in the case of Ted, childhood cancer at the age of 12 which caused the amputation of his right leg, and severe mental and substance abuse problems in the case of Patrick.

All that grief and sorrow never stopped Ted Kennedy from becoming one of the greatest senators in the history of the U.S. Farrell’s exhaustive look at his life fills one full of wonderment as to just how he coped and kept going despite all the tragedy.

Of course, there is the controversial Ted Kennedy, who walked away from Chappaquiddick in 1969 leaving Mary Jo Kopechne to drown in the car he had just driven into a pond.

There was his excessive drinking, his womanizing, and his political failures as time and again his vision of winning the White House was thwarted.

To say Kennedy lived a full life is to understate his achievements. As a senator, he played a huge role in President Lyndon Johnson’s Civil Rights Act of 1964. He was also the chief creator of the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act, also signed by Johnson.

That legislation, however, turned out to be one of Kennedy’s most dramatic political mistakes from which America still suffers today. Kennedy assured the Irish among others that the new bill would not impact their visa numbers, but the exact opposite happened and the patchwork solutions for immigration reform since 1965 have all pretty much crashed and burned.

Looking for Irish book recommendations or to meet with others who share your love for Irish literature? Join IrishCentral’s Book Club on Facebook and enjoy our book-loving community.

Farrell makes clear that Kennedy was one of the first to see through the smoke and confusion surrounding America’s presence in Vietnam and the call for withdrawal, as did his brother Robert when they both finally realized the U.S. generals were making up the “facts” on the ground as they went along.

Kennedy was also responsible for Barack Obama’s groundbreaking Obamacare bill. His ambition for the last half of his career was to pass health care for all. Kennedy’s endorsement of Obama over Hillary Clinton in the 2008 Democratic primaries ensured the Obama victory, in return for which Obama gave his promise to focus on health care no matter what.

The more you read Farrell’s biography, the more you realize that there has not been a significant act or achievement over the last 40 years that Ted Kennedy did not play a role in.

In terms of the Supreme Court, he stopped Robert Bork’s nomination in 1987 and had him replaced with Anthony Kennedy, who became the key swing vote on the court.

Of course, we cannot forget Northern Ireland. Without Kennedy, the Gerry Adams visa to travel to the U.S. in 1994, at a critical point in the peace process, would not have happened. Kennedy was a strong voice in the Senate that Ireland needed at critical times.

In the end, Farrell makes clear that despite Chappaquiddick, despite all the hatred aimed at him from the right wing, Kennedy emerged as a giant with no modern-day equivalent in terms of impact and importance in American politics. He may not have become president, but in a strange way, he became more powerful, able to spend nearly 47 years as one of the greatest legislators in the history of American politics.

Farrell knows his subject well, and he paints the different shades of Kennedy brilliantly, from heroic politician to alcoholism, to a man of vision unseen in American politics since the time of FDR.

Comments