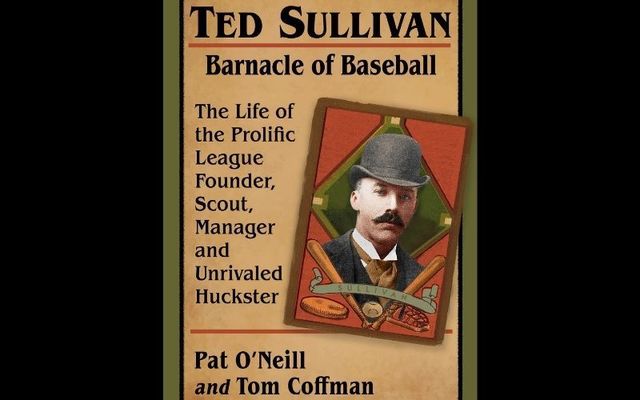

A new book aims to tell the story of famous Irish-born baseball scout and manager Ted Sullivan for the very first time.

"Ted Sullivan - Barnacle of Baseball" by Pat O'Neill and Tom Coffman tells the fascinating story of a figure synonymous with America's game in the early 1900s.

Although Sullivan was omnipresent in the early years of baseball, he has been almost completely forgotten about today.

Looking for Irish book recommendations or to meet with others who share your love for Irish literature? Join IrishCentral’s Book Club on Facebook and enjoy our book-loving community.

O'Neill, a former Colorado newspaper editor who currently serves as President of the Kansas City Irish Center, and Coffman, a media relations specialist who has worked as a reporter and editor, aim to rectify that by documenting the life and times of the famous scout, manager, broker, and author.

You can read an excerpt from Coffman and O'Neill's fascinating book below.

“Ted Sullivan needs no introduction to baseball fans, for to introduce him would be to introduce baseball, itself. Mr. Sullivan is so well known in the baseball world that if you would, in the blissfulness of your ignorance plaintively ask ‘Who is Ted Sullivan?’ You would thereafter be shunned and avoided as a person of unsound mind.”

The Abilene Texas Daily Reporter, March 25th, 1920

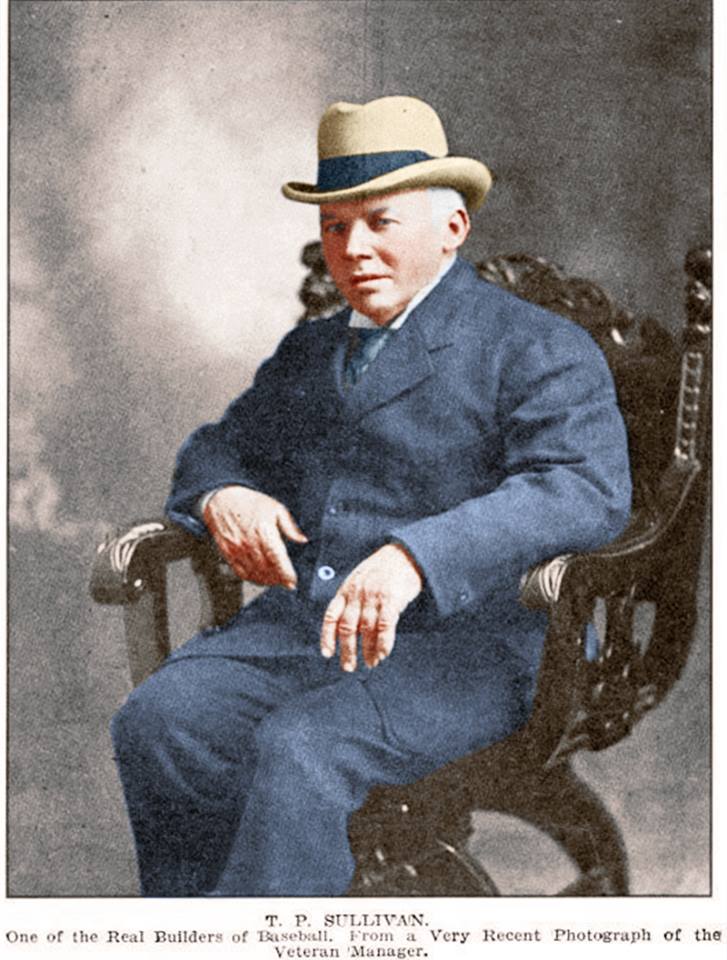

In his day, perhaps no one in American baseball was better known than Irish-born Timothy Paul “Ted” Sullivan. For 50 years, sportswriters sang his praises and bought his blarney by the barrel. Some even went so far as to call him “the daddy” of America’s game. A more cynical Damon Runyon dubbed him “The Barnacle of Baseball.”

In his brief but palmy playing days of the 1870s and ‘80s, he was described as “a red-cheeked, sturdy little Irishman, very much undersized for a pitcher. He was good-natured, crafty, a chatterbox when wound up, very proud of his ancestry and himself.”

Young Sullivan learned America’s game on the playground of St. Gall’s school in Milwaukee, and cut his baseball molars in the old “dead ball” era, when the rubber-cored sphere was squishy and lopsided. When pitchers rubbed dirt, licorice, spittle, and tobacco juice into the ball to make it nearly invisible to the batter. When ballfields were often converted farm pastures still pocked with rocks and cow patties.

Cunning, fast-talking, witty, charming, serious and sober, Sullivan became the game’s first player agent, a renowned scout who pulled future hall of famers from the bushes, an author, a playwright and a baseball evangelist who promoted the game across five continents. He coined the term “fan,” and was among the first to suggest the designated hitter.

McFarland.

But his foremost talent may have been the telling of tall tales.

He once claimed to have used a dead pitcher to finish a game, and, while managing a team in New Haven, Ct., he (falsely) touted his star twirler, “Wolf-Eating Bear,” as a hatchet-throwing Native American with 60 scalps to his credit. His favorite fibs, though, had to do with finding “phenoms” way back in the woods.

SULLIVAN CLAIMS TO HAVE A “PHENOMENAL” PITCHER FROM MINNESOTA

SPENT THE WINTER BREAKING BARN DOORS FOR PRACTICE

Milwaukee Sentinel March 27, 1896

“The baseball fraternity are eagerly awaiting for funny Ted Sullivan to announce the name of the ‘phenomenon’ that breaks two inch planks at fifty feet,” wrote a tongue-in-cheek scribbler back in St. Louis, while the Omaha Bee cagily noted that Sullivan, “a sharp, shrewd man and one of the best known base-ball men in America” was a bit like George Washington, “for once in a while—alack—he is known to tell a story.”

Over his long and colorful life, the irrepressible Sullivan touched every facet of baseball. But he found his most lasting fame as an organizer of ambitious baseball roadshows. He took the White Sox on a heralded exhibition tour through Mexico – maybe the longest on-ground road trip ever – in 1907. But his coup de grace was the arrangement and management of “The World’s Tour of Baseball” in late 1913 and early 1914.

After trotting his ballplayers into Japan, China, The Philippines, Australia, Egypt, Italy and France, had hoped to conclude the historic tour in Dublin on George Washington’s birthday. But weather and other factors made that impossible, so it was on to London for the last hurrah. As a product of Eire, the manager of the world tour was less than eager to deal with the self-possessed British, but anxious to make a show of his and the tour’s success.

Behind his hand, Sullivan regularly referred to English King George’s domain as “Swelldom,” and believed that the Americans, “with their magnetic gingery temperament,” would never be able to assimilate with the English, given the latter’s “frigid-zone temperament.”

Ultimately, Ted Sullivan’s London show came off without a hitch. In deference to the king and with a nod to political ecumenism, Irish pitchers were, as “Hotspur,” a.k.a. Albert Feist of Britain’s Daily Telegraph put it, “taboo for the day.”

Love Irish history? Share your favorite stories with other history buffs in the IrishCentral History Facebook group.

At least 25,000 Brits, including one mystified sovereign, saw the Sox beat the Giants, 5–4, in extra innings. The takeaway from Harper’s Weekly was that, “though he [King George] might not have imbibed much wisdom, he was certainly entertained, as the royal smile never faded, from the first inning to the last.”

Timothy P. “Ted” Sullivan’s last great scheme was to bring Ireland’s Gaelic football heroes, The Kerrymen, to the United States in 1927 for a series of exhibition matches designed to raise funds for GAA facilities and programs back in Ireland. On arrival in America, the Kerry stars were treated like visiting potentates. But expectations soon went sideways, , with the Irish heroes getting beat by a crack team of Irish ex-pats in front of 30,000 people at the Polo Grounds in New York. Subsequent exhibitions in Boston, Hartford, New Haven and Chicago went better, but ticket sales slumped well short of goal.

Father Edward Fitzgerald, the brother of Gaelic football legend Dick Fitzgerald, had helped Sullivan organize and promote the Kerry team’s tour of the states. But toward the conclusion of the tour, Irish tempers flared, with many, including the priest, feeling that hustling Sullivan had picked the team’s pocket by palming more than his share of the gate receipts. Ninety-two years later, the slight still festers in the late clergyman’s bio on the official website of the Diocese of Cork & Ross (Ireland): “In 1927, he organized an American tour for the Kerry team. He traveled out ahead of the team. Unfortunately, he had very few happy memories of this historic event, as a member [whose initials were likely T. P. S.] of the organizing committee misappropriated most of the funds, from which upset he never fully recovered.”

Sullivan maintained his innocence and believed his heart was always in the right place, especially when it came to the sport he loved most. Reaching the end of his days, he lamented that he had “helped players in my life that were not known—that nobody cared for; they were as blank on the baseball market as if they never existed. In their obscurity they were pulled out of mines, off drays, and other humble positions. I pushed them to the front with no gain for myself, but with sympathetic heart, and I never in my life heard one of those people say ‘Thank you.’”9

The man who a generation of sports writers called “The Daddy of the Game” died alone and largely unnoticed on July 5, 1929, in Gallinger Hospital in Washington, D.C. Even the Washington Post missed the news, the hospital having filed Sullivan’s death notice under his real name: Timothy Paul Sullivan. Not Ted.

Comments