The romance and myths of the American Revolution have long obscured the disproportionate contributions of the Irish, who numbered as high as a half million of America’s two million population.

George Washington Park Custis, Washington’s adopted son and a careful student of history, placed the significant Irish contribution to the American Revolution in a proper historical perspective:

“When our friendless standard was first unfurled for resistance, who were strangers [foreigners] that first mustered ‘round its staff when it reeled in the fight, who more bravely sustained it than Erin’s generous sons? Who led the assault on Quebec [General Montgomery] and shed early luster on our arms, in the dawn of our revolution? Who led the right wing of Liberty’s forlorn hope [General Sullivan] at the passage of the Delaware [just before the attack on Trenton]? Who felt the privations of the camp, the fate of battle, or the horrors of the prison ship more keenly than the Irish? Washington loved them, for they were the companions of his toil, his perils, his glories, in the deliverance of his country.”

Yet, the role of the Irish has often been written out. No chapter of America’s story has been more thoroughly dominated by myths and romance than the nation’s desperate struggle for life during the American Revolution. Unfortunately, America’s much-celebrated creation story has presented a sanitized version of events.

The long-accepted proper imaginary of the typical American patriot was that of an Anglo-Saxon who descended from early English settlers. This popular perception became a permanent part of the national mythology, in regard to the people who were seen as having been most responsible for sustaining and winning the revolutionary struggle.

As could be expected, the seemingly endless romantic myths about America’s founding were created as part of the usual process of countries constructing self-serving myths for national self-gratification.

Americans today believe that the upper-class elite, especially the Founding Fathers, and the traditional New England model (the popular romantic New England stereotype of the middle-class yeoman soldier of Anglo-Saxon descent) were most responsible for America’s success in the revolutionary struggle.

But this romanticized focus of America’s creation story from the top has overlooked what was actually more significant in determining a winner from a loser during the American Revolution: the historical, republican, and cultural legacies brought to America by hundreds of thousands of Irish immigrants before the war’s beginning and the disproportionate contributions of the Irish from 1775 to 1783.

Without sufficient resources to purchase land, lower-class Irish settlers had pushed toward the setting sun in search of land and the promise of a fresh start.

Here, on the western frontier, they created distinctive ethnic communities, like “Little Ireland,” and “Little Dublin,” before the American Revolution, while laying America’s most sturdy foundation for resistance to the so-called Mother Country. After all, England was the ancient enemy of the Irish people, and she was definitely no Mother County to them.

Most of all, it was the lowest-class colonists who made the most important contributions to America’s ultimate victory over an extended period. They were the ones who fought and died in disproportionate numbers (as in leading the way west—literally an Irish vanguard—and settling the western frontier) to make America an independent nation. And no social class in America was lower (after African slaves, of course) than the Irish, who served in the ranks in large numbers from every colony (later states) during the revolutionary struggle.

Unfortunately, the romance and myths of the American Revolution have long obscured the disproportionate contributions of the Irish, who numbered as high as one half million of America’s two million population.

But these extensive contributions by the so-called lower class “mob” from the point of view of the wealthy, aristocratic revolutionary elite, including the Founding Fathers, were overlooked for political, economic, and social reasons (not to mention prejudices) that became so deeply ingrained in American life.

But what cannot be denied was the notable fact that the Irish responded to the call of liberty en masse.

However, because so many of these diehard patriots were recent immigrants from Ireland and members of the lowest class, they were considered outsiders and foreigners, especially Irish Catholics, who were not deemed worthy of mention by generations of America’s leading historians and scholars.

Mostly from the northeast, these influential Anglo-Saxon historians possessed ample good reason to obscure the truth about America’s creation story. Quite simply, without the disproportionate and significant contributions of the Irish on all levels (political, military, and economic), America would not have won its struggle for independence. In consequence, the Irish Odyssey during the American Revolution is one of the best untold stories of American history.

Indeed, the Irish played disproportionate roles in every phase of America’s struggle for liberty because the Irish already fully understood (unlike the majority of colonists of British descent) what would become America’s tragic fate, if Great Britain was allowed to turn this land of plenty into another Ireland.

The commonalities between the longtime struggle of the Irish people of liberty on the Emerald Isle and America’s fight for independence were remarkable. No one more than General George Washington realized as much.

In a stirring tribute, he later emphasized to the Irish people how “your cause is like unto mine.” Against the odds, the Irish had long fought in vain to establish their own people’s republic, but they were unable to overcome the might of a vast empire’s superior resources and manpower.

Therefore, with Ireland’s searing historical lessons in mind, the Irish served in the ranks with distinction, including more than 20 generals. In a desperate bid to make Canada the 14th Colony at the end of December 1775, General Richard Montgomery was killed in a swirling snowstorm during the desperate attack through the streets of Quebec, Canada, to become America’s first national martyr.

General John Sullivan, who was the son of Irish immigrants served as one of Washington’s trusted top commanders. Generals Montgomery, who had attended Trinity College, Dublin, and Sullivan, who led one of the two assault columns in Washington’s victory at Trenton, New Jersey, on December 26, 1776, that saved the day for America, were two of Washington’s best fighting generals. Sullivan was only one of five brothers who fought for America’s liberty: a good representative example of the totality of the Irish commitment to liberty.

Other hard-hitting Irish generals served Washington exceptionally well. Hailing from Dungiven, County Londonderry, John Haslet was another one of Washington’s gifted Irish generals, who was as dependable as he was capable. He was killed in leading the attack at Princeton, New Jersey, on January 3, 1777. The lowly son of Ulster Province immigrants and a hero of the battle of October 1777 Saratoga, New York, that garnered the all-important French Alliance, General Daniel Morgan was a truly gifted leader on every level. He then won the most tactically brilliant victory of the American Revolution at the battle of Cowpens, South Carolina in mid-January 1781, helping to pave the way for the dramatic final victory of Washington and the French allies during the decisive showdown at Yorktown, Virginia.

General “Mad” (a name bestowed for his sheer combativeness not his mental state) Anthony Wayne was proud of the fact that his Irish grandfather fought with distinction at the decisive battle of the Boyne. Washington’s right-hand man and innovative leader of the Continental Army’s artillery arm, General Henry Knox, was the son of humble Irish immigrants from County Derry. General John Stark was an old Indian fighter, the son of Northern Ireland immigrants, and a tactically innovative commander. Stark’s many key battlefield accomplishments, especially at Trenton and Bennington, became legendary. Stark fought and won vital victories by the fiery motto: “Live free or die—death is not the worst of evils.”

Love Irish history? Share your favorite stories with other history buffs in the IrishCentral History Facebook group.

Most importantly, new evidence in the form of primary documentation has now revealed that Washington’s Continental Army consisted of a far larger percentage of Irish soldiers than previously thought by historians—between 40% to 50% during the most crucial periods of the revolutionary struggle.

However, this recent revelation has coincided with the view of James Galloway, a former high-ranking Pennsylvania political leader who was in the know. He testified before an investigative committee of Parliament how “the majority of the men who fought against England in America were of Irish extraction.”

In turn and significantly, Galloway’s views corresponded with the contemporary words of the soldiers, both officers and enlisted men (British and Hessian), who fought against the Irishmen of liberty. In a revealing July 18, 1775 letter, Lieutenant William Fielding wrote how “above half [of the American Army consisted of] Irish and Scotch” [Scotch-Irish from Northern Ireland] soldiers. As if knowing that America would eventually win its independence because of the overwhelming Irish participation in the struggle, one British official lamented how: “the Irish [Gaelic] language was as commonly spoken in the American ranks as English.”

So many Irish served in the ranks of the Pennsylvania Continental Line, the backbone of Washington’s Continental Army and one its largest units, that this hard-fighting unit was correctly known as the “Line of Ireland.” Not surprisingly, therefore, St. Patrick’s Day was widely celebrated in Washington’s Army with considerable enthusiasm.

Clearly, the courageous Irishmen who fought for America were no ordinary players. John Barry, an Irish Catholic born in Ballysampson, County Wexford, earned well-deserved renown as the “Father of the American Navy.” A disproportionate number of Irish from the Williamsburg District, South Carolina, served as daring partisans under the famous “Swamp Fox” of the American Revolution, Francis Marion. Marion and his band of never-say-die partisans kept the fires of resistance alive and helped to turn the tide in South Carolina, when American fortunes in the South were at their lows.

Such impressive examples of significant Irish contributions to America’s independence are almost without end. Quite simply, the Irish were the very heart and soul of America’s resistance effort from beginning to end.

In the end, the greatest dream of the Founding Fathers, including Washington, came true because of what the most forgotten players of the American Revolution accomplished both on and off the battlefield. But the Irish made far more than just disproportionate battlefield contributions. Eight signers of the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776, were foreign-born, more from Ireland than any other country. Charles Carroll was the only Catholic signer. He traced a proud lineage back to the O’Carroll family of County Kings. Even more, Carroll never lost his faith in Washington’s generalship, supporting him when he was under heavy criticism. Irish merchants of Philadelphia and other communities, including on the western frontier, across America, provided invaluable economic support for the resistance effort.

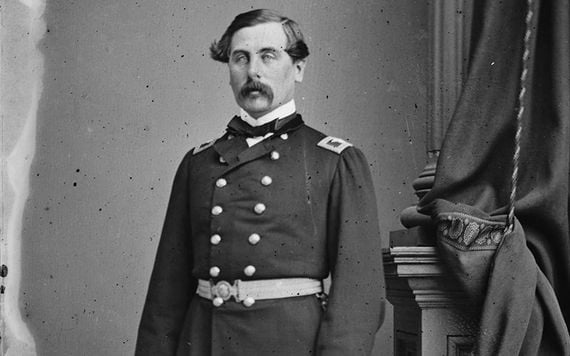

Thomas Francis Meagher.

Famed Irish revolutionary Thomas Francis Meagher, who fought on American soil and led the Irish Brigade with distinction during the Civil War, emphasized a truism that applied directly to the American Revolution: “Whether in the camp or the field, or in the loud thunders of the battle, with death or victory staring him in the face, [the typical Irish fighting man on American soil] sees not death, he sees only his beloved Ireland [because] Ireland inspires him to deeds of valor, which beckons him to heroism in the cause of liberty.”

But perhaps a high-ranking French volunteer, the Marquis de Chastellux, said it best: “Congress owed its existence, and America possibly her preservation to the firmness and fidelity of the Irish.” No one was more thankful than Washington for how the Irish literally saved the revolution by their commitment, faith, and sacrifice year after year. Consequently, the “Father” of the United States of America never forgot how “Ireland, thou friend of my country in my county’s most friendless days.”

For ample good reason and most importantly, Luke Gardiner (the future Lord Mountjoy) emphasized the most forgotten reason that explained how and why America won its independence. In no uncertain terms and in presenting the most forgotten truth about the American Revolution, he declared to the House of Commons in Parliament “You have lost America by the Irish.”

----------------------------

The ground-breaking new book by Phillip Thomas Tucker, Ph.D., "How the Irish Won the American Revolution, A New Look at the Forgotten Heroes of America’s War of Independence" (New York: Skyhorse Publishing, 2015) was published in October 2015.

*Originally published in 2015, updated in Sept 2023.

Comments