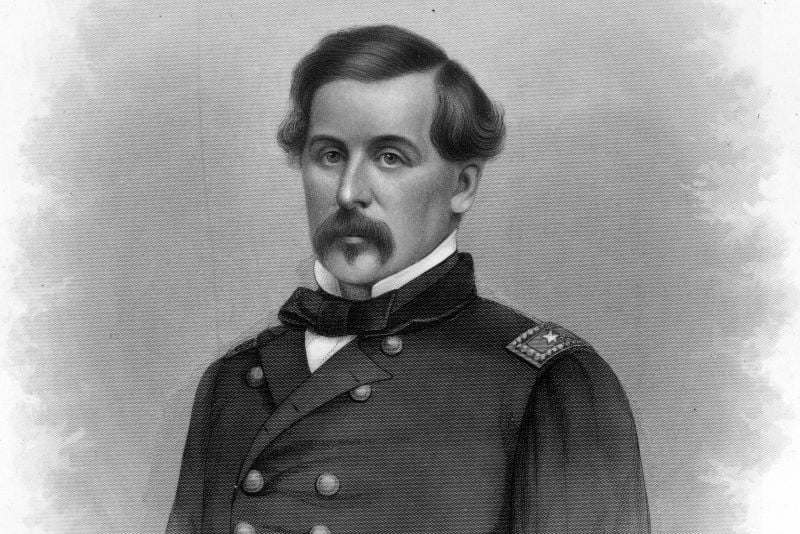

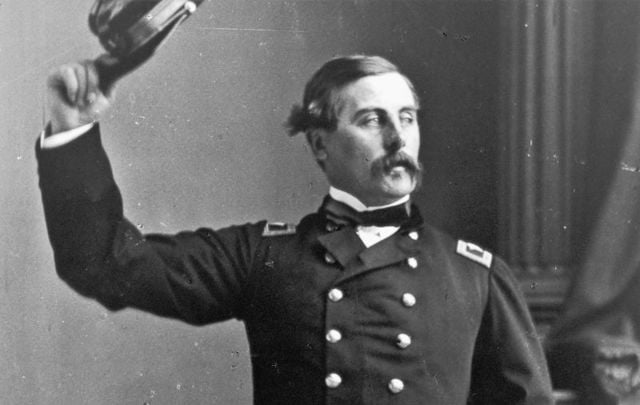

On this day, July 1, 1867, General Brigadier Thomas Francis Meagher died after falling overboard on the Missouri River. In honor of his anniversary, we look at the astounding biography of the American Civil War hero and leader of the Irish Brigade.

Although he lived only a short 44 years, Thomas Francis Meagher, who was born in Co Waterford in 1823, played a pivotal part in two of the most important movements in the histories of Ireland and the United States.

Yet today, to many Americans and Irish alike, Meagher is a distant landmark of history, the Civil War hero who, early in the war, guided the “Fightin’ 69th” and following their success was asked to form the famed Irish Brigade.

New York Times Pulitzer Prize-winning columnist Timothy Egan knew nothing of Meagher when he literally stumbled upon him.

“Quite by accident,” Egan confessed to IrishCentral.

“After a visit to Ireland in 2009 with my family, I was looking for a way to tell an Irish American story. And then I found Meagher. I bumped into him, sort of—the statue outside the Montana capitol, in Helena. I’d never heard of Meagher until I saw the statue, and that started me down a curious road.”

But the story of Meagher starts long before the American Civil War. It begins in Waterford, Ireland where he was born into privilege in 1823. Well-educated in both Ireland and England by his politically-connected father, Meagher was appalled at what he saw the English doing to Ireland.

On the first page of "The Immortal Irishman," Egan writes: “You would not think in Irish, so the logic went if you were not allowed to speak in Irish.”

The English stripped the Irish of their culture—then introduced famine.

“Today,” said Egan, “we would call it ethnic cleansing. It’s also close to apartheid. Basically, the English did everything they could to strip away the basic dignity of a people. They took religion, language, sport, property, even music. And all it did was make the Irish more defiant. They clung to their religion, they made the harp a national symbol, they even started a hurling club in the first British colony, in Newfoundland—all as a way for a conquered people to remain Irish.”

Love Irish history? Share your favorite stories with other history buffs in the IrishCentral History Facebook group.

Meagher grew up during one of the most interesting periods in Irish history. One of the treats of "The Immortal Irishman" is Egan’s wonderful description of the Young Ireland movement of the 1840s. First, there was O’Connell’s emancipation of the Catholics; then the Young Ireland movement with Thomas Davis, John Mitchel, William Smith O’Brien, and Oscar Wilde’s mother, Speranza—and Meagher knew all of them personally (Meagher and Speranza were even thought to be lovers).

IrishCentral asked Egan how great was the influence of the Young Irelanders, not only on Meagher but on the Fenians of 1867 and the rebels of 1916?

“Meagher and Young Ireland influenced both the Fenians and the Easter Rising rebels,” replied Egan.

“You can see his influence in a book Arthur Griffith wrote about the time of the Rising, praising Meagher, and resurrecting his words. The Young Ireland slogan—Ireland for the Irish—was basically the same as the young rebels used in 1916.”

The thing that galvanized Meagher and the Young Irelanders was the Famine, which devastated Ireland during the 1840s, cutting the island’s population almost in half. Egan takes a good look at Charles Trevelyan, the man put in charge of famine relief. Trevelyan, a fine Christian man, thought the famine was sent from God, as a means of ridding the English of the lazy Irish—a “selfish, perverse and turbulent people” according to Trevelyan—always looking for a handout. “Being altogether beyond the power of man,” Trevelyan said, “the cure has been applied by the direct stroke of an all-wise Providence.”

When reminded that we still hear this type of stuff out of American politicians during election cycles as they cite the need to cut food stamps to the poor—pitting the “givers” against the “takers”—Egan said, “Yeah, I actually wrote a New York Times column on this. I was in the middle of researching the famine and Paul Ryan’s comments came to mind. It started a pretty vigorous discussion in Irish America magazine as well.”

General Brigadier Thomas Francis Meagher.

Meagher also was close to John Mitchel, one of the weirdest Irish nationalists to ever breathe—a true political schizophrenic. In Ireland he was for freedom; in America, he was for slavery and against Blacks, and, especially, against President Lincoln. (Mitchel considered the slaves “an innately inferior people.” He also described President Lincoln as “an ignoramus and a boor.”)

Meagher was fiercely anti-slavery and a personal friend of Lincoln.

“A very strange relationship,” said Egan of the Meagher-Mitchel friendship.

“They were very tight in Ireland; Mitchel had Meagher’s back. Meagher was the voice; Mitchel the pen. Then they reunited in both Tasmania and America. But things got dicey in the U.S. Mitchel was a white supremacist, and he ended up losing (I think) two sons, who fought on the side of the slaveholding Confederacy. As I recall, one of the Mitchel boys was on the other side of Marye’s Heights wall when Meagher’s Irish Brigade charged.”

The “Rebellion of 1848” was really a skirmish in Co Tipperary, but it was cited by Patrick Pearse (“six times during the past three hundred years they have asserted it in arms” Pearse wrote in the 1916 Proclamation) as one of the times that the Irish had risen up in arms against the British.

Betrayed by an informer, it also cost Meagher his freedom when he was convicted of sedition, although he wasn’t even present at the “Battle of Ballingarry.” His death sentence was commuted and he was exiled to Tasmania.

Life down-under wasn’t too bad for Meagher because his family had money. He lived well and found a wife. (They were to have one child, which Meagher would never meet because of his banishment from Ireland.) But he longed for freedom. As other convicts had done, under harrowing circumstance, he escaped to America.

“America was a fascinating mess” his friend Richard O’Gorman told Meagher on Meagher’s arrival in New York. There was the problem of all the new immigrants and the nativist backlash of the “Know-Nothings.”

Things haven’t changed a lot in over 150 years, have they? If you exchanged the Irish for the Latinos it’s just about the same policy.

“So true,” agrees Egan.

“A point I try to make. It shows that, even though we’re a nation of immigrants, this anti-immigrant nativist streak comes and goes; it’s never far from the surface.”

The “Know-Nothings” went after Irish Catholics with a ferocity that America would not see until the civil rights battles of the 1960s. They terrorized the Irish in such cities as Philadelphia and Boston, burning churches to the ground, but did not succeed in New York principally because of the stand taken by “Dagger” John Hughes, the County Tyrone-born, toupee-wearing archbishop, the man who started building St. Patrick’s Cathedral.

Yet as the Civil War and the military draft took center stage the moral compass of Hughes was compromised and in the case of John Mitchel, utterly destroyed. Meagher stood strong, backing the Union and remaining strongly anti-slavery. “Meagher originally was an agnostic on slavery,” says Egan. “But he changed his view, and changed rather dramatically, after all the sacrifices the Irish Brigade made on behalf of the Union cause—which was, after all, the cause for liberation of black men. Once he came to that conclusion he was all in. And you saw, in the draft riots, that it would have cost him his life at the hands of fellow Irish had he been in New York when the rioting broke out.”

Read more

The heroics—and sacrifices—of Meagher’s men at places like Bull Run, Richmond, Antietam and Fredericksburg was instrumental in allowing the Irish to be accepted as Americans. “They were amazing warriors,” says Egan, “and no one thought they’d be able to fight at the start of the war. But they also kept their cultural traditions intact; they essentially took them to war—the horse races, the feasts, the masses, the plays, the poetry readings, and music.”

"The Immortal Irishman" is Egan’s seventh book and took him three years to write. His previous books include "The Big Burn," "Short Nights of the Shadow Catcher" and "The Worst Hard Time," for which he won a National Book Award. There are many colorful characters—Meagher himself, O’Connell, Thomas Davis, Mitchel, Smith O’Brien, Dagger John, General Sherman, Lincoln, etc. in "The Immortal Irishman."

Did Egan ever think of making the book a novel? “No,” he replies definitively. “Here was a case where truth was much better than fiction. If you made up the dozen lives of the period no one would believe you.”

Meagher received his general’s commission directly from President Lincoln. “Lincoln liked Meagher and vice versa,” says Egan, “even though they were in different political parties. Lincoln made time to see Meagher even when he saw no one else. Lincoln shrewdly named Meagher a general as a way to win over the Irish masses to the Union cause.”

Love Irish history? Share your favorite stories with other history buffs in the IrishCentral History Facebook group.

After his first wife’s death, Meagher remarried in New York and after the Civil War, the couple were sent to the Montana territory by President Andrew Johnson where Meagher soon found himself the Acting Governor. There was a lot of lawlessness out there and Meagher fought the battle on the side of the angels. It may have caused his death because Egan believes, Meagher was murdered by his opponents. “I do. And I think that’s the emerging consensus view of historians in Montana who’ve looked at him in the last ten years or so. The earlier story of his death was bullshit.”

One of the things that strikes the reader of "The Immortal Irishman" is the similarity between Meagher and another Irishman—John F. Kennedy. Both were born into privilege; Meagher came from Waterford and Kennedy’s people came from the next county north, Wexford; both were extraordinarily handsome with keen intellects; both were the greatest orators of their day; both were war heroes; both were heroes of the civil rights movements of their time; and both were murdered in their middle-40s.

Did these similarities occur to Egan? “They did. And I’m glad you noticed. I only picked this up when I was looking for an ending and starting going through stories of JFK’s family, and the trip to Ireland. Many, many similarities—the charisma, the speechifying gift, the warrior heroism, the love of verse.”

Thomas Francis Meagher, a man not only for his time, but an Irishman for all time.

*Dermot McEvoy is the author of "The 13th Apostle: A Novel of a Dublin Family," "Michael Collins, and the Irish Uprising and Irish Miscellany" (Skyhorse Publishing). He may be reached at dermotmcevoy50@gmail.com. Follow him at DermotMcevoy.com. Follow The 13th Apostle on Facebook.

*Originally published in 2017, updated in July 2024.

Comments