“They are a stupid, sodden, vicious lot, most of them being equally deficient in brain and virtue.”

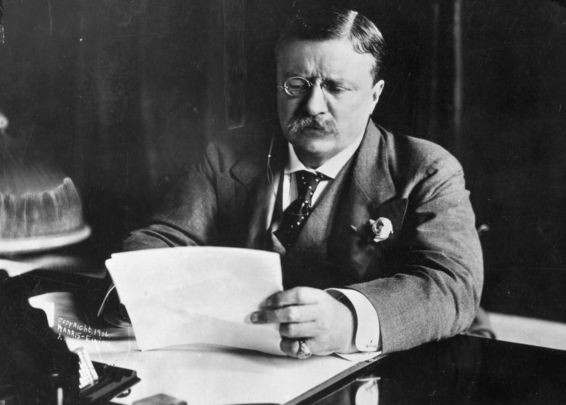

These are not the remarks of some irrelevant 19th-century racist, rather they are the writings of a young Theodore Roosevelt before he served as the 26th President of the United States.

Roosevelt concluded in his diary entries that “the average Catholic Irishman of the first generation as represented in this assembly, is a low, venal, corrupt and unintelligent brute.”

Roosevelt’s comments are indicative of an anti-Irish sentiment that swept across the United States following the Irish famine of 1845-1850 when hundreds of thousands of Irish immigrants left Ireland behind in search of a new life in America.

His comments came in January 1882, when he served as a New York State Assemblyman.

Roosevelt, a Republican, was immensely frustrated by the Democratic majority in the New York legislature, a frustration that was only exacerbated by a strong Irish influence in the Democratic Party.

Irish Democrats in the New York Legislature, of which Roosevelt writes there 25, established themselves in Tammany Hall which housed the Democratic Party Machine in New York City.

They were crucial to the Democratic majority in the legislature and Roosevelt clearly resented them for it.

In earlier writings, Roosevelt said that over half of all Democrats, including almost Irish Democrats, were "scoundrels."

"Over half of the Democrats, including almost all of the City Irish, are vicious, stupid-looking scoundrels with apparently not a redeeming trait, beyond the capacity for making ludicrous bills."

Read more: The NYC newspaper editor who spoke out against “No Irish Need Apply”

Roosevelt's sentiments mirrored a societal anti-Irish prejudice during the era. Anti-Irish racism was rampant in 19th century America and "No Irish Need Apply" signs - commonplace in the United Kingdom - began to spring up in the United States.

A newspaper illustration including the "No Irish Need Apply" sign in a shop window.

Protestant American Nativism - a political policy of promoting the interests of native inhabitants over those of immigrant communities - was rife in the second half of the 19th Century and it led to widespread discrimination against Irish Catholics.

Irish Catholics would eventually become the "preferred" ethnic minority among natives as they vented their ire towards Italian Catholics and Russian Jews instead.

19th century America is a far cry from the America of today, where an inherently positive, pro-Irish sentiment is almost ubiquitous.

It is difficult to imagine an America where the Irish communities weren't venerated, but it was certainly the case for Roosevelt's America and it undoubtedly contributed to his unexpected sentiments.

He is widely regarded as one of America's best-ever presidents and will always be remembered for his conservation work and for his pioneering of the Panama Canal.

He has been immortalized in stone on Mount Rushmore for his efforts as president.

But, for a time, this great president expressed the same anti-Irish prejudice that was so commonplace on both sides of the Atlantic and it's something that can't be overlooked.

He did, however, express a keen interest in Irish literature and was particularly fond of Lady Gregory and Douglas Hyde. Roosevelt was allegedly fanatical about Irish mythology and acutely aware of the goings-on in pre-revolution Ireland. Perhaps he realized the errors of his younger judgments.

Are you shocked by Roosevelt's words? Were you previously aware of them? Let us know in the comments section below.

Comments