On January 16, 1913, the third reading of the “Government of Ireland Bill” more commonly known as the Third Irish Home Rule Bill was passed through the House of Commons in London.

Two weeks later it was to be once again rejected—for the third time—by the House of Lords who aligned with the Unionists—living mainly in Ulster— and feared that the introduction of Home Rule would spell a break up for the union of Ireland and England.

For once, this rejection in the House of Lords did not spell a journey back to the drawing board for the advocates of Home Rule in Ireland. With thanks to the Parliament Act in 1911, the House of Lords no longer had the power to defeat a bill, simply delay it, meaning that Home Rule was still to be implemented but with a bit of a wait.

The Home Rule Bill was a piece of legislation that would remove the governance of Ireland from England and return it to Ireland. Following a failed rebellion involving French assistance in 1798, the Act of Union, 1800, was put in place, essentially meaning that the Irish no longer engaged in a personal union with England with the Protestant Ascendancy ruling over the country from Dublin, they were now ruled directly from London.

Attempts to repeal this union began immediately with “The Emancipator”, Daniel O’Connell fighting for its end throughout the 1840s.

Earlier this week, we saw the anniversary of his first public speech arguing against the Act of Union to a group of Catholics in Dublin in which he declared that it would be better to return to the days of the Penal Laws than to spend any more time in such a union with England.

"Let every man who feels with me proclaim, that if the alternative were offered him of Union, or the re-enactment of the Penal Code in all its pristine horrors, that he would prefer without hesitation the latter, as the lesser and more sympathizers proclaimed to the Catholic meeting on January 13, 1800, “that he would rather confide in the justice of his brethren the Protestants of Ireland, who have already liberated him than lay his country at the feet of foreigners."

The concept of Home Rule, however, only came to popular attention in Ireland in the 1870s, following further failed uprisings in 1803, 1848, and 1867.

In 1870, Isaac Butt, a barrister and former Tory MP, founded the Irish Home Government Association. Using a cross-section of progressive landowners, tenant rights activists, and supporters and sympathizers of the failed Fenian uprising of 1867, Butt and the association evolved into the Home Rule League which earned the alliance of many Irish MPs.

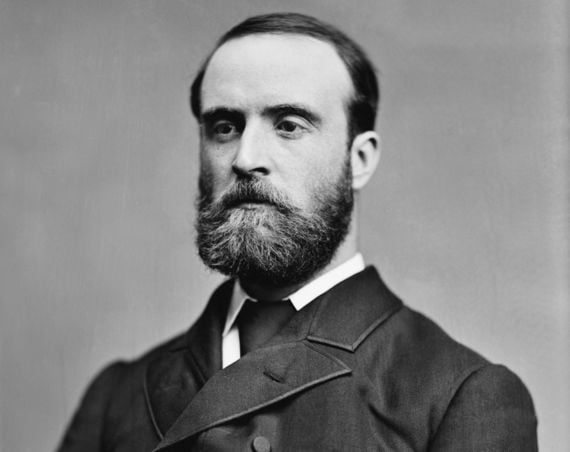

The movement would be revitalized yet again with the introduction of the master organizer Charles Stewart Parnell as leader, turning the Home Rule effort into a powerful political force from parish to parliament level.

Charles Stewart Parnell.

By the time it finally passed in 1913, it was the third time a Home Rule Bill was brought in front of the English Houses of Parliament. The first came in 1886 under the Liberal government of Prime Minister William Gladstone with the support of Parnell and the Irish Parliamentary Party. The Bill did not even pass the House of Commons.

The second attempt came in 1893 with Parnell recently deceased and although it passed the House of Commons, it was rejected in the House of Lords.

It wasn’t until 19 years later under Herbert Asquith’s Liberal government that the bill returned. For two general elections, Asquith and his party had held onto power by forming an alliance with the Irish Nationalist Party and its leader John Redmond. A condition of this alliance was to finally deliver on Home Rule for Ireland.

The Bill was successfully passed through the two houses at the beginning of 1913 because of the reduced powers of the House of Lords.

Unfortunately for the Home Rule party, the outbreak of the First World War in 1914 sent the British government into emergency mode and the Home Rule Bill was once again placed on the long finger.

Love Irish history? Share your favorite stories with other history buffs in the IrishCentral History Facebook group.

With the promise of its immediate implementation at the closing of the war, John Redmond delivered a rousing speech to Irish Volunteers in which he encouraged them to support the British cause against Germany.

As a largely Protestant country attempting to assert its power over smaller Catholic countries, many were happy to be obliged to fight against Germany and many even enlisted in the British Army to fight in the trenches.

There was a minority, however, who were unhappy with the English once again not meeting a demand and felt that Redmond was weak in bending to another excuse instead of implementing the Home Rule on time. Among this minority were the leaders of the 1916 Rising who were not prepared to wait any longer to regain power from Britain.

Seeing WWI as England’s difficulty and Ireland’s opportunity, they organized the 1916 Easter Rising, a failed uprising that nonetheless rekindled the flames of rebellion among the Irish people and is being celebrated this year as one of the most significant events on the road to Irish independence.

The Home Rule Bill was never to be.

* Originally published in 2016, updated in 2025.

Comments