The sheer scale of the American Civil War makes it often impossible to comprehend. The great armies, grand charges and huge casualty figures that typify the conflict make it difficult for us to bridge the gap of time and experience that separates us from those who were there in the 1860s. Narrowing our view to look at the stories of individuals and small groups is one way of getting us closer to understanding the reality of war. It is much easier for us to grasp the impact of momentous events on a single person or family, as it allows us to relate directly to human experience.

I am fascinated by the individual story. They are at once emotive and powerful, and can serve to illustrate wider truths regarding the impact of conflict. They also demonstrate that the American Civil War continued to affect people well beyond 1865. We often forget that the stories of those who survived the conflagration did not end at Appomattox or Bennett Place. We would like to think that the people who had endured four years of war had experienced the worst that life had to throw at them. The reality for some was that the decades after 1865 did not bring the reward and respite they may have deserved. Such was certainly the experience for Bernard Quinn.

Bernard Quinn was born in Co. Monaghan around the year 1835. It is not clear when he immigrated to the United States, but he may be the Bernard Quinn who sailed from Liverpool aboard the Lucy Thompson, anchoring in New York on May 26, 1857. Either before he left Ireland or after his arrival in America Bernard worked as a baker, but he soon decided on a career change. On September 12, 1857 the young man approached Lieutenant Updegraff of the U.S. Army and decided to enlist for a five-year term. Perhaps he wanted financial security or sought adventure – perhaps both; either way his decision began what would be a long association with the military.

Bernard was described in 1857 as 5 feet 8 inches in height, with blue eyes, sandy colored hair and a fair complexion. He became part of Company H of the 4th United States Infantry, a regiment with a strong Irish contingent.

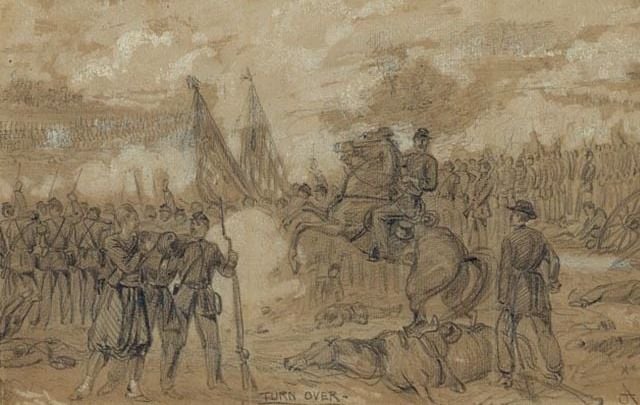

In the years before the outbreak of the Civil War the 4th saw service on San Juan Island and on the west coast. With the coming of hostilities in 1861 the 4th returned to the east, becoming part of Sykes division of regulars in the Army of the Potomac. Their first actions of the war were on the Peninsula, and they played a notable role in the Battle of Gaines’ Mill. Bernard served with the regulars up until September of 1862, when his term of enlistment expired on September 12. The five-year veteran left the ranks just prior to the Battle of Antietam.

The Monaghan man did not take long to get back into the fray. On September 23, 1862, only days after his discharge, Bernard enlisted as a Corporal, in the largely Irish, 13th Pennsylvania Cavalry. He remained with them for the duration of the war, serving with the Army of the Potomac and in the Valley Campaign before joining up with Sherman for the conflict’s conclusion in North Carolina. He mustered out with his comrades in Philadelphia on July 14, 1865.

For the next ten or so months Bernard tried civilian life in Philadelphia – it may be that he returned to his previous profession as a baker. However, it wasn’t long before he decided on another stint in the military.

He was still only 30 years of age when on May 18, 1866 he enlisted again, this time for three years. Although his profession was once more recorded as ‘baker,’ in reality Quinn was a now soldier through and through. Having already tried the infantry and cavalry, this time he had joined the 1st United States Artillery.

The unit spent the majority of the late 1860s on garrison duty, and Bernard eventually rose to the rank of Sergeant. His final term in the military ended on May 18, 1869, when Bernard was discharged and walked out the gates of Fort Wadsworth on Staten Island and into permanent civilian life.

During his time in the military Bernard Quinn had been associated with three branches of the service – infantry, cavalry and artillery. He also chose variety in the cities he lived in; having initially arrived in New York, he had spent time in Philadelphia and eventually decided that his future lay in New Bedford, MA. It seems probable that he had problems readjusting to civilian life, and that things were never quite the same for Bernard after 1869. The decades passed with little word of Bernard Quinn. However, he re-emerges in 1905, in a newspaper article that charted the tragedy of the veteran’s final years:

PENSION CAME TOO LATE

Old Ragman Was Drowned When About to Receive It.

New Bedford, Mass., November 5. – One the eve of receiving a fortune that would make him independent for the remainder of his life, Bernard Quinn, 71 years old, was drowned in the Acushnet River. His body was found floating near a wharf by fishermen.

For 15 years the man had been a familiar sight about the streets, and his only visible wealth was two ragbags which were generally filled with assorted rags. The man was to come into possession of a back pension estimated to be at least $5,000 within a few days.

Quinn, who was known in this city as “Old Barney,” was born in Ireland, and enlisted in the Army after coming to this country. He served in Company H, Fourth Infantry, and also in Company K, Thirteenth Pennsylvania Volunteers.

After the Civil War he served a third enlistment in the regular Army, holding the rank of corporal and sergeant. While in this city the old man made his headquarters at the City Mission, and was always in destitute circumstances.

A short time ago Congressman William S. Greene was interested in the man, and through his influence the first payment on a back pension, amounting to thousands of dollars, was to have been paid.

So ended the sad story of Bernard Quinn. His life was far more than simply a record of service between 1861 and 1865, though it seems his years in the military may well have been among his happiest. The image of a young, heroic member of Sykes Regulars at Gaines’ Mill in 1862 contrasts sharply with the destitute ragman floating in the Acushnet River four decades later. But this was the same man, the immigrant baker turned soldier, who ended his days as a ragman.

When we look at those who lived through the Civil War we should try to examine their entire life experiences, not just the heady days of their youth on the battlefield. Such poignant stories make it all the more tragic that Ireland does not today do more to remember those born on this island who experienced the American Civil War. The story of Bernard Quinn from Co. Monaghan is just one of hundreds of thousands written by Irish immigrants in the United States. The creation of the Irish diaspora and Irish emigration is a major part of Ireland’s history. We should spend more time exploring them, discussing them, learning from them and remembering them.

* Damian Shiels is an archaeologist and historian who runs the IrishAmericanCivilWar.com website, where this article first appeared. His book 'The Irish in the American Civil War' was published by The History Press in 2013 and is available here.

Comments