“Joseph, my little man, be a priest if you can.”

Michael Mallin to his 2-1/2-year old son hours before his execution.

On September 13, 1913 Dublin was in turmoil as working men were “locked out” by their employers. Amazingly, in this crucial time in Irish history, Joseph Mallin was born. One-hundred-and-four years later, Father Mallin is still with us. He deserves great congratulations for that alone, but there is something much more special here. Father Joe is the only surviving child of any of the 1916 martyrs, the son of Commandant Michael Mallin, the man in charge of the St. Stephen’s Green battalion of the Irish Citizen Army (ICA). Father Joseph’s survival is almost a prick to the Irish conscience, reminding us of how the nation, in revolution, was born, and the sacrifices that were shared by many during the Rising and the War of Independence.

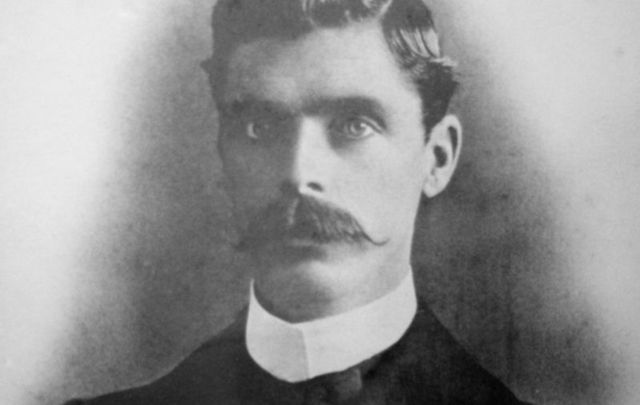

Fr Joseph Mallin.

Recently, IrishCentral ran a piece on Father Mallin. In that article Father Mallin defended his father against British accusations that he tried to deny that he was the commandant in charge of the St. Stephen’s Green rebels, who were based at the College of Surgeons. Rereading Father Mallin’s treatise I believe that most of Father Mallin’s contentions are correct. I also agree with Father Mallin’s assertion that his father’s fatal destiny was deeply tied to the fate of the Countess Markievicz, Mallin’s second-in-command at the Green.

But I think the disparagement of the characters of both Mallin and Markievicz by the secret British court-martials go beyond the normal British-Irish antagonisms. I believe it had a lot to do with them being members of James Connolly’s Irish Citizen Army (ICA), an organization pledged to the defense of the working man and the downtrodden.

The Taking of St. Stephen’s Green

Both the Irish Volunteers and the Irish Citizen Army were created in November 1913. The Volunteers were formed in response to the arming of Protestants in the North and the Citizen Army was created in response to the labor riots that hit Dublin in August and September of that year where workers were savagely clubbed by members of the Dublin Metropolitan Police in Sackville Street. The two organizations remained separate entities until January of 1916. At that time, the Volunteers—secretly controlled by the radical Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB)—fearing that James Connolly, commandant-general of the ICA, might preemptively start a rising on his own, “kidnapped” Connolly and filled him in on their plans for an insurrection at Easter. Although Connolly was now conspiring with the Volunteers led by the likes of Tom Clarke, Seán MacDiarmada, Joseph Plunkett and Padraic Pearse, his ICA largely remained a separate military body.

James Connolly.

On Easter Monday both armies were ready to go until mobilization orders were countermanded by Eoin MacNeill, titular head of the Volunteers. This order took the steam out of the proposed Rising. The next morning, Easter Monday, the rebellion was on again. Almost all the outposts of resistance in Dublin—GPO, Four Courts, Boland Mills, Jacob’s Factory and the South Dublin Union—were manned by Irish Volunteers. And although Connolly himself was in the GPO, his ICA was busy up at St. Stephen’s Green where they took the College of Surgeons. The ICA also branched out to take the Harcourt Street Railroad Station, the City Hall next to Dublin Castle, Davy’s Pub on the Grand Canal and Kingsbridge (now Heuston) Station. All these missions proved largely unsuccessful, most probably because of a lack of manpower. Abbey Theatre actor Seán Connolly—no relation to James—became the first nationalist casualty of the Rising at the City Hall.

On St. Patrick’s Day 1916 Connolly took many of his men on a walking tour around Dublin and made military suggestions. At the Green, he pointed at the Shelbourne Hotel and suggested it might be wise to commandeer it because of its location, height and amble provisions. On Easter Monday, with his ICA short many men—500 were expected, 150 showed up—because of MacNeill’s orders of Sunday, Michael Mallin, the commandant in charge of the Green’s occupation, did not take the Shelbourne. Soon the British took advantage of this strategic blunder, placed machine guns on its roof, and controlled the Green. It was a mistake that doomed Mallin’s St. Stephen’s Green strategy. The siege of the Green went on for a week until Pearse’s surrender orders, countersigned by Connolly, which led Mallin to yield his post at the College of Surgeons.

Mallin and Markievicz’s Surrender

The surrender of the Green’s insurgents begins the libel of Mallin and Markievicz. Mallin surrendered his post at the College of Surgeons to Captain Henry de Courcy Wheeler. Wheeler stated that “The prisoner [Mallin] and the Countess of Markievicz came out of the side door of the College [of Surgeons]. The prisoner was carrying a white flag. And was unarmed but the countess was armed. The prisoner came forward and saluted me and said he wanted to surrender and this is the Countess Markievicz. He surrendered and stated he was the commandant of the garrison.” Markievicz also told Wheeler that “she was second in command.” It is colorfully recounted that the Countess kissed her revolver before turning it over to Wheeler.

Thus, you have the two commandants in command of Stephen’s Green readily admitting their status to the British officer who took their surrender.

The Trial of the Countess Markievicz

Things, according to the British, began to change at the trials. Markievicz was first on May 4th. Her trial was prosecuted by Lieutenant William Wylie. At her trial she said, “I went out to fight for Ireland’s freedom and it doesn’t matter what happens to me. I did what I thought was right and I stand by it.”

According to Wylie she said, “I’m only a woman. You cannot shoot a woman, you must not shoot a woman.” Wylie went on to note that “She never stopped moaning the whole time… We all felt slightly disgusted. She had been preaching rebellion to a lot of silly boys, death and glory, die for your country etc. And yet she was literally crawling. I won’t say anymore. It revolts me still.”

Yet a Lieutenant Bucknill, who was present, recalls her saying “‘We dreamed of an Irish Republic and thought we had a fighting chance.’ Then for a few moments she broke down and sobbed.”

Anyone who knows of Markievicz’s personality would doubt the scene that Wylie swore he saw and heard and Bucknill said he didn’t. According to Brian Barton in From Behind a Closed Door: Secret Court Martial Records and the 1916 Easter Rising, “Wylie’s willful and scurrilous distortion of her response at her trial is difficult to interpret.” Barton goes on to speculate that “It may reflect a personal sense of irritation at her self-assurance and boldness, which he may have considered an insult to the court. Perhaps it reflected deep-rooted sexual prejudice and rank misogyny on his part. More likely, his fictitious account sprang, above all, from a feeling that the Countess had by her actions betrayed both her religion and her class (she had been presented at court to Queen Victoria in her jubilee year, 1887).”

Markievicz was sentenced to death which was not commuted to penal servitude for life for two days by General Maxwell, the man now signing the death warrants for the leaders. The Countess took it all in stride, declaring, “I do wish your lot had the decency to shoot me.”

Michael Mallin Is Libeled by Brigadier General Maconchy

Mallin was brought to Richmond Barracks for his court-martial. He was not the most important man at his trial—Brigadier General Ernest Maconchy was. Why? Because it is Maconchy who first put the lie to Mallin’s story.

Maconchy was a career British Army officer, serving exclusively in India—the same location that Mallin served when he was in the British Army. With the outbreak of revolution in Dublin, Maconchy was sent to Ireland, commanding the 2nd Sherwood Foresters who saw rough action around Boland Mills and the South Dublin Union. He would also be the one to judge Michael Mallin at court-martial. In his memoirs, he states that “When called on for their defence they generally only convicted themselves out of their own mouths, and in many cases I refused to put down what they said as it only made their cases worse.”

Brigadier General Ernest Maconchy.

“…[A]nd in many cases I refused to put down what they said as it only made their cases worse.” In those words, Maconchy reveals the lie to his words. We cannot be sure what Mallin said because Maconchy admits he may have fiddled with the wording. It should be emphasized that there was no court reporter; the only record of what was said are Maconchy’s notes.

Michael Mallin faced what many of the married rebel leaders faced—the quandary between love of Ireland and love of family. Mallin—with a pregnant wife and four children—according to Maconchy’s court records, tried to downplay his role in the rebellion and put the onus on Countess Markievicz who he incorrectly described as his superior.

Mallin at his court-martial—according to Maconchy—declared: “I am a silk weaver by trade and have been employed by the Transport Union as band instructor. During my instruction of these bands they became part of the Citizen Army and from this I was asked to become a drill instructor. I had no commission whatever in the Citizen Army. I was never taken into the confidence of James Connolly. I was under the impression we were going out for manoeuvres on Sunday but something altered the arrangements and the manoeuvres were postponed till Monday. I had verbal instructions from James Connolly to take 36 men to St. Stephen’s Green and to report to the Volunteer officer there. Shortly after my arrival at St. Stephen’s Green the firing started and the Countess of Markievicz ordered me to take command of the men as I had been so long associated with them. I felt I could not leave them and from that time I joined the rebellion. I made it my business to save all officers and civilians who were brought in to Stephen’s Green. I gave explicit orders to the men to make no offensive movements and I prevented them attacking the Shelbourne Hotel.”

An aerial shot of modern day St. Stephen's Green.

In a memo to Prime Minister Asquith, General Maxwell said: “This man was second in command of the Larkinite or Citizen Army with which organization he had been connected since its inception.” His sentence was death.

With his sentence in hand Mallin seemed to embrace what he had done. He wrote to his wife: “I do not believe that our blood has been shed in vain. I believe Ireland will come out greater and grander but she must not forget she is Catholic, she must keep the faith…I must now prepare these last few hours must be spent with God alone. Your loving husband Michael Mallin, Commandant, Stephen’s Green Command.”

To his parents he wrote: “I tried with others to make Ireland a free nation and failed. Others failed before and paid the price and so must we.”

Before his execution he was described by his priest as being “serene, though very much affected.” He was shot May 8th between 3:45 and 4:05 a.m.

How the British army in India comes into play

Much of Father Mallin’s defense of his father is tied to two things: 1) the prejudice and animosity the British felt towards former British soldier Michael Mallin; 2) and the British efforts to tie the fate of Mallin to Markievicz, who the British desperately wanted to shoot. As Father Mallin states in his thesis, “General Maxwell wanted Commandant Mallin’s court martial record to show that Countess Markievicz was in command and thereby to support his expressed intention to execute the Countess.”

Both Maconchy and Mallin had served together in India. Father Mallin wrote that “Maconchy’s whole career was in India and another member of the court, [Lieutenant Colonel A.M.] Bent, had spent at least 25 years of his military career in India. It goes without saying that they would most definitely be serving the interest of the British Army; the expressed intensions of their commanding officer General Maxwell; and by extension their own military careers. Their impartiality must be questioned.

“They knew my father from his military service in India and as British army men they would have regarded him as a traitor to their uniform. My father fought on the 1897-1898 Tirah campaign on Indian/Afghanistan border, as did Brigadier Maconchy. My father received a medal and Maconchy received his DSO (Distinguished Service Order) on the Tirah. When my father came before Maconchy for court martial, it is reasonable to believe, that Maconchy would have regarded him as a treasonous former soldier, a disgrace to the British uniform and shooting alone would not be good enough. Treason for a serving soldier, or former soldier, of the British army would be judged far harsher by its military court than if that person were a civilian rebel. Therefore, it can be assumed that, in the eyes of the court-martial, Commandant Michael Mallin’s treason was twice the treason of a civilian rebel. Is it not conceivable therefore, that this secret court-martial would use all means at their disposal to punish and discredit him, this… treasonous double traitor?”

“A profound injustice to my Father”

Going on Maconchy notes, Father Mallin states that his father said, “ ‘I had no commission whatever in the Citizen Army……and that….the Countess of Markievicz ordered me to take command of the men.’ I believe that the veracity of the court-martial record does not stand up to critical examination for all of the reasons outlined in this letter. However, the inference of these two statements has been interpreted by some writers and historians to mean that my father tried to transfer the responsibility for the Command of the St. Stephen’s Green Garrison to Countess Markievicz and thereby avoid his own execution. That interpretation is a profound injustice to my father. My father would never have put the life of a comrade at risk as this would have been contrary to everything he believed in and lived by. The archival records confirm his leadership qualities and give first-hand accounts of how my father put his own life at risk to save the lives of his comrades, for example, wounded ICA volunteer, Philip Clarke. My father had no fear of death, he was a soldier, and he had faced death on more than one occasion in India and in Dublin. I believe the court-martial record to be untrustworthy and a questionable account of the court proceedings, the motives for which are examined and presented in this letter. My belief is confirmed by the account of the British Army officer, Captain Henry de Courcy-Wheeler, who took my father’s surrender at St. Stephen’s Green, and who also gave evidence at my father’s court-martial. My belief is further confirmed by the President of the court-martial, Brigadier Ernest Maconchy, who claimed in his memoir that his written records are, in many cases, his own words and therefore not a verbatim account of the court-martial proceedings. But above all I believe my father was an honourable man who would not shirk his responsibility and definitely not a person who would risk the life of a dear friend and comrade. My father was a religious man, a man of faith, with deeply held Christian values.”

No collaboration from the court

Father Mallin also stated that “The junior members of the court [Lieutenant Colonel Bent and Major F.W. Woodward] did not sign Maconchy’s document or provide their own written accounts of the trial. The fact that his document has not been endorsed or corroborated by the other members of the court is significant. Especially since the written words are, by Maconchy’s own admission…in many cases his own words. Therefore, this uncorroborated document is one man’s own account of court proceedings at a secret trial. It certainly must not be taken to be a verbatim account of the proceedings.”

The Countess Markievicz is the target, Mallin the Patsy

“I believe,” Father Mallin continued, “it can be reasoned that the record of my father’s court-martial was a deliberate attempt by the British Military to provide General Maxwell, Commander-in-Chief in Ireland with evidence to support his expressed intension to execute Countess Markievicz if she was found guilty. While at same time smear the good name and character my father, an honourable man and former British soldier. The reasoned arguments are presented below: General Maxwell, Commander-in-Chief in Ireland, is on record as saying that he intended to execute Countess Markievicz if she was found guilty. …… ‘I intend to try her [Markievicz] as she is bloody guilty & dangerous. I am of the opinion that this is the case of a woman who has forfeited the privilege of her sex’…… The court-martial of my father, Commandant Michael Mallin of the Irish Citizen Army is inextricably linked to the court-martial of Countess Markievicz not only because of her high public profile and involvement with the Irish Citizen Army but also because of the expressed intensions of General Maxwell.

“Countess Markievicz was court-martialed, found guilty and sentenced to death on the 4th of May,” continues Father Mallin, “but the court martial verdict was not announced, and it had no validity, until General Maxwell the confirming officer, considered her trial record and confirmed the verdict and sentence. Maxwell delayed confirming the sentence on Markievicz for two days. My father was court-martialed, found guilty and sentenced to death, on the 5th of May. The delay in confirming sentence on Countess Markievicz provided the British Military with an opportunity to provide further evidence to support their Commander-in Chief’s [Maxwell] expressed intension to execute Countess Markievicz. My father’s court-martial provided that opportunity.

“Countess Markievicz was one of the high-profile personalities of the rising,” declares Father Mallin, “therefore curiosity alone would have made Brigadier Maconchy, the court president at my father’s trial, enquire as to the outcome of the Markievicz trial. It is reasonable to assume that his fellow officer Brigadier Blackader, the court president at the Markievicz trial, would have no difficulty in disclosing this information to Brigadier Maconchy. Countess Markievicz was found guilty and sentenced to death on the 4th of May, the day before my father’s court-martial. Therefore, if Brigadier Maconchy already knew the verdict of the Markievicz court-martial, it is conceivable that Maconchy was attempting to strengthen the hand of his Commander-in-Chief, and when he wrote the words… Countess of Markievicz ordered me to take command of the men…. was he not patently bolstering Blackader’s verdict of guilty against Markievicz? As already stated, Brigadier Maconchy, in his memoir, makes no secret of the fact that in many cases he wrote the words for the prisoners himself.”

Father Mallin cites extreme prejudice

Father Mallin makes the case for extreme prejudice from the officers of the court, all of whom had connections to the British Army in India. “The consequences for my father from his career in the British army: My father served over 13 years in the British Army with the Royal Scots Fusiliers, more than six of which were spent on the North-West Frontier in India. It is well known that my father frustrated the British Army hierarchy on at least four significant occasions: 1) When my father was serving with the British Army in India he was called on to give evidence at the trial of an Indian man accused of shooting a British Officer. The man was being tried by military court. All of the witnesses were from the military including my father but he was the only witness to state that the accused man was innocent of the charge. My father’s statement was contrary to the view of the court and not well received by the military hierarchy. The Indian man was found guilty by the court-martial, sentenced to death and hanged. 2) During his time in India with the British Army he refused to contribute to a collection for Queen Victoria’s birthday and he was outspokenly critical of the Queen for religious reasons. By today standards this might seem petty but at that time his outspokenness would not have gone unnoticed to the hierarchy of the British Army. It would be regarded as an insult to their queen and would be held against my father by the senior ranks of the British army. 3) He refused a promotion and a bounty if he would stay on and complete 21 years in the British Army. He refused this offer in no uncertain terms. 4) He again rejected an offer of a promotion if he would re-enlist in the British army at the outbreak of the First World War. Given that Brigadier Maconchy spent his whole military career in India it is highly likely he was well aware of the background to these, and other events concerning my father. It can be reasoned that these events influenced Brigadier Maconchy’s opinion of my father and before the court martial began.”

The important points behind Father Mallin’s arguments

To recapitulate Father Mallin’s case:

- The trial transcripts cannot be trusted because they were written solely by General Maconchy who brazenly stated: “in many cases I refused to put down what they said as it only made their cases worse.”

- Commandant Mallin’s history in the British Army played against him at his trial. Father Mallin states: “…it is reasonable to believe, that Maconchy would have regarded him as a treasonous former soldier, a disgrace to the British uniform and shooting alone would not be good enough.”

- The fate of Mallin and Markievicz are tied together. Father Mallin: “…the record of my father’s court-martial was a deliberate attempt by the British Military to provide General Maxwell, Commander-in-Chief in Ireland with evidence to support his expressed intension to execute Countess Markievicz if she was found guilty.” Father Mallin goes on to conclude that: “…Maxwell delayed confirming the sentence on Markievicz for two days. My father was court-martialed, found guilty and sentenced to death, on the 5th of May. The delay in confirming sentence on Countess Markievicz provided the British Military with an opportunity to provide further evidence to support their Commander-in Chief’s [Maxwell] expressed intension to execute Countess Markievicz. My father’s court-martial provided that opportunity.”

The forgotten element—the Irish Citizen Army

The reasons behind why the British decided to execute sixteen men in 1916 vary. Seven were shot because they had signed the Proclamation: Padraig Pearse, Clarke, MacDonagh, MacDiarmada, Plunkett, Ceannt and Connolly.

Daly and Heuston were executed because they out-soldiered their British counterparts. Daly was also the brother-in-law to Clarke, so an additional message was being sent. Heuston should not have been executed, neither should have Colbert. MacBride was shot for being a persistent foe of the British going back to the Boer War. O’Hanrahan was third in command at Jacob’s and probably should not have been shot either. Kent in Cork definitely should not have been shot. Willie Pearse was shot because he was the brother of Padraig; sheer vindictiveness. Casement was shot because the British thought he had betrayed them, being a former government official. Number 16, of course, would be Mallin.

The animosity aimed at Mallin and Markievicz was unique because the other rebels were often praised by their captives for their convictions and bravery in the face of death. Prosecution Counsel William Wylie—the Countess Markievicz adamant foe—described Padraig Pearse speech at trial as “very eloquent…what I always call a Robert Emmet type.”

Brigadier General C.G. Blackader said of Pearse: “I have just done one of the hardest things I have ever had to do. I have had to condemn to death one of the finest characters I have ever come across. There must be something very wrong in the state of things that makes a man like that a rebel. I don’t wonder his pupils adored him.”

Wylie also said: “I was always sorry MacDonagh was executed. It was particularly unnecessary in his case.”

So why the extreme animosity towards Mallin and Markievicz at their trials? One-point Father Mallin did not make is that they, along with Connolly, were the only representatives of the Irish Citizen Army. Connolly had to be shot because he signed the Proclamation, but Mallin and Markievicz only had manned the Green and had manned it with an underwhelming understanding of military strategy. It might be said that all commandants were shot, but this is not true. De Valera and Thomas Ashe, both of whom inflicted heavy casualties on the British, were not shot.

I think the targeting of Mallin and Markievicz may have a lot to do with their being members of the ICA. The labor riots of 1913 had left their mark on not only the Irish working man, but also on the British establishment. At the time of the riots poverty was peaking in not only Ireland but in all of the British Isles. Working men were making as little as £1 a week and women were receiving even less, 12 shillings.

The Lockout pitted James Larkin and Connolly against William Martin Murphy, the most powerful employer in Dublin. What Larkin soon found out is that the British Trade Union Congress would not stand up for their fellow union members in Ireland. “Larkinism” because an epithet to the British establishment. Now in time of war it was something they did not need as the war was going very badly for them.

Jim Larkin went off to America and was replaced by the equally militant James Connolly who gave warning to the establishment by parading his newly formed ICA around Dublin. The next time the Dublin Metropolitan Police tried to club them, they would fight back and fight back hard.

Mallin had a low profile around Dublin, but the Countess Markievicz was outspoken and flamboyant, not unlike the actress she formerly was. She was a champion of the working class although she came from the Anglo-Irish governing class.

Besides all the machinations that Father Mallin chronicled in his report, is it safe to say that the execution and the near-execution was a call-out to the ICA and Larkinites that they would not be permitted to stir up hostilities in this time of the Great War?

In the end, although General Maxwell wanted to execute Markievicz, it came down to her sex and the Countess was spared. Michael Mallin had a lot of sins in the eyes of the British—former British soldier, commandant of the Stephen’s Green command, refusing to re-up for the Great War—but his final sin may have been the worst of all, he was ICA and in a time of reckless, stupefying war, was for the working-class, the greatest sin of all.

* Dermot McEvoy is the author of the The 13th Apostle: A Novel of Michael Collins and the Irish Uprising and Our Lady of Greenwich Village, both now available in paperback, Kindle and Audio from Skyhorse Publishing. He may be reached at [email protected]. Follow him at www.dermotmcevoy.com. Follow The 13th Apostle on Facebook.

Comments