William Balch, an American minister, historian and journalist visited Ireland during the Famine year 1850. We pick up his journey as he approaches Millstreet in Cork in dreadful weather.

“Our road now lay, after a few miles, through a rough, wild, mountainous country much of the way. We passed along narrow defiles, through boggy meadows, and under lofty mountains, following a small stream to its very source in a large bog, from which we descended into a small valley running between two ranges of jagged, barren mountains, in which is situated the little dirty town of Millstreet. We passed several ruined castles on our way; among them Carrig-a-Phouca, somewhat in the style of Blarney, though more dilapidated, having been built by the McCarthys, in the early style of castle architecture.

In the course of the afternoon, it came on to rain in torrents. We were wholly unprotected from the ”pelting of the pitiless storm.” An English naval officer, on the seat before us, was sheltered by a good mackintosh cape, a corner of which I borrowed without his knowledge, to shield my knees. He also had a large blanket under him, which he preferred to keep there, rather than offer it to us. Another gentleman of the same nation, on the right, had an umbrella, which he contrived to hold just so as to pour an additional torrent upon one of our company, never offering to share it with us.

The poor fellows behind, and one forward, were as bad off as ourselves, except Mr. Red-coat, who bundled himself up with several cloaks and took it patiently. There was not a passenger inside and had not been all day. Six might have been shielded from the storm, perhaps, from sickness and untimely death. But to enter was not permitted, inasmuch as we had taken outside seats, and neither the driver nor the guard had any option in the case — we suppose they had not. Humanity is the boast of John Bull. This is an illustration of it.

At Millstreet, we stopped a few minutes, and most of the passengers took a lunch. A loaf of bread, the shell of half a cheese and a huge piece of cold baked beef were set upon the table in the dirty bar-room. Each went and cut for himself, filling mouth, hands and pockets as he chose. Those who took meat paid a shilling; for the bread and cheese, a sixpence. The Englishmen had their beer, the Irishmen their whiskey, the Americans cold water.

Our party came out with hands full, but the host of wretches about the coach, who seemed to need it more than we, soon begged it all away from us, and then besought us, ” Please, sir, a ha’penny, oond may God reward ye in heaven.” A woman lifted up her sick child, in which was barely the breath of life, muttering, ” Pray, yer honor, give me a mite for my poor childer, a single penny, oond may God save yer shoul.”

Several deformed creatures stationed themselves along the street, and shouted after us in the most pitiful tones. Others ran beside the coach for half a mile, yelling in the most doleful manner for a” ha’penny,” promising us eternal life if we would but give them one.

We observed that the Englishmen gave nothing, but looked at them and spoke in the most contemptuous manner. We could not give to all, but our hearts bled for them. We may become more callous by a longer acquaintance with these scenes of destitution and misery; but at present the beauty of the Green Isle is greatly maiTed, and our journey, at every advance, made painful by the sight of such an amount of degradation and suffering [sic].

Love Irish history? Share your favorite stories with other history buffs in the IrishCentral History Facebook group.

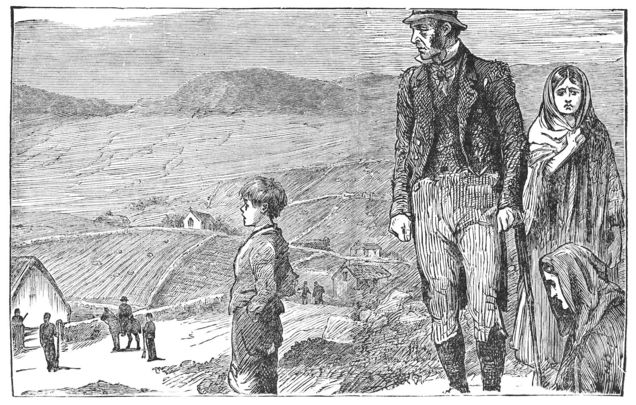

At one place, we saw a company of twenty or thirty men, women and children, hovering about the mouth of an old limekiln, to shelter themselves from the cold wind and rain. The driver pointed them out as a sample of what was common in these parts a year ago. As we approached, ascending a hill at a slow pace, about half of them came from the kiln, which stood in a pasture some rods from the road. Such lean specimens of humanity I never before thought the world could present. They were mere skeletons, wrapped up in the coarsest rags. Not one of them had on a decent garment.

The legs and arms of some were entirely naked. Others had tattered rags dangling down to their knees and elbows. And patches of all sorts and colors made up what garments they had about their bodies. They stretched out their lean hands, fastened upon arms of skin and bone, turned their wan, ghastly faces, and sunken, lifeless eyes imploringly up to us, with feeble words of entreaty, which went to our deepest heart. The Englishmen made some cold remarks about their indolence and worthlessness and gave them, and gave them nothing.

I never regretted more sincerely my own poverty than in that hour. Such objects of complete destitution and misery; such countenances of dejection and woe, I had not believed could be found on earth. Not a gleam of hope springing from their crushed spirits; the pangs of poverty gnawing at the very fountains of their life. All darkness, deep, settled gloom! Not a ray of light for them from any point of heaven or earth! Starvation, the most horrid of deaths, staring them full in the face, let them turn whither they will. The cold grave offering their only relief, and that, perhaps, to be denied them, till picked up from the way-side, many days after death, by some stranger passing that way, who will feel compassion enough to cover up their moldering bones with a few shovels-full of earth!

And this a Christian country! a part of the great empire of Great Britain, on whose domain the ” sun never sets,” boastful of its enlightenment, its liberty, its humanity, its compassion for the poor slaves of our land, its lively interest in whatever civilizes, refines, and elevates mankind! Yet here in this beautiful Island, formed bv nature with such superior advantages, more than a score of human beings, shivering under the walls of a lirriekiln, and actually starving to death!

* Originally published in 2016, updated in Nov 2023.

Comments