In 1971 I returned to Dublin for the first time since my family immigrated to New York in 1954. On my to-do list was to visit the matriarch of the McEvoy family, my Aunt Kathleen, who lived in Great Western Square in Phibsborough in Dublin.

Kathleen was a legend in the family. She was born Catherine McEvoy in Clogher Head in County Louth (not too far from Termonfeckin, the dirtiest-sounding town in all of Ireland!) in 1897.

She was to be the first of 14 children born to my grandparents, John McEvoy and Katie Dillon. She was famous for her kindness to her brothers and sisters, many of whom she helped immigrate to America.

She was a devout Catholic and would become a mother to a priest and a nun. She knew the hardness of life for a young girl on a farm. Although never stated, there was always disappointment when a female child was born because she could not physically work the farm. Thus, by 1916 she found herself working as a servant girl in Dublin.

Since 1966, the 50th anniversary of the Easter Rising, I’d developed a keen interest in Irish revolutionary history. My father was given the gift of a book, "The Irish Uprising 1916-1922," which had many photos and a great deal of text related to the insurrection. There was also a record narrated by CBS correspondent Charles Kuralt, with music supplied by the Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem. Many of the old rebels told their stories on the record. The first time I saw a photo of Michael Collins and read of Bloody Sunday, I was hooked.

Being the suspicious, cynical New Yorker I am, I asked Aunt Kathleen if the revolution was as bad as it seemed. She looked me straight in the eye and told me that in 1916 she had seen British soldiers shoot innocent men and it had marked her for life. After the Easter Rising, she had gone out and joined the Cumann na mBan, the women’s auxiliary of the IRA. The British had turned this country girl with strong religious convictions into an urban revolutionary.

Aunt Kathleen’s story stuck in my head, but I didn’t know the specific details of what, exactly, she had been involved in. In Dublin, my cousin Terry O’Neill, Kathleen’s grandson, began to fill in the pieces. He learned that Kathleen had been at the Louth Dairy at 27 North King Street during Easter Week. In fact, when she married Dick Bartley at Halston Street (St. Michan’s) Church in 1918, she put that address down as her home. (I am told by another cousin, Kathleen’s son Monsignor Vincent Bartley, that Kathleen became life-long friends with Mrs. May Lawless and I now believe that she probably went to work at the Louth Dairy after the Rising and also resided on the premises.)

For years now, I’ve suspected that Kathleen, because she lived on North King Street, was talking about the North King Street Massacre when she spoke to me in 1971. Terry’s legwork brought verification of this belief in the form of witness statements that the survivors made before the Coroner’s Court in May 1916.

The aftermath of the 1916 Easter Rising on O'Connell Bridge.

Daly and Heuston Make the British “See Red”

The murders of fifteen innocent civilian men on North King Street were the direct result of the military brilliance of Commandant Ned Daly at the Four Courts and Captain Seán Heuston directly across the Liffey at the Mendicity Institute. (Both of them were executed in May 1916.) Heuston, with few men, held the British off for 50 hours as they tried to advance across the Liffey from the Royal (now Collins) Barracks to reinforce Dublin Castle. At the Four Courts Daly’s men advanced down Church Street, just to the left of the Courts, and reached North King Street where they bloodily met the British. (Church and North King is also the same street where Kevin Barry would be unluckily captured by the British four years later.)

The British officer in charge of the area said, “This whole neighborhood was strongly held by the rebels, who had elaborately prepared and fortified it against the military with barricades across the street, and by taking out house windows and sandbagging them, etc.”

Apparently, the beating that Daly and Heuston put on the British did not go down well. To put it mildly, the men of Daly and Heuston out-soldiered their British opponents. In the North King Street area, the British suffered losses of 16 dead and 31 wounded. Their frustration with the rebel’s guerrilla street warfare might have been the reason they turned vicious against the local innocent civilians and—as General Sir John Grenfell Maxwell, K.C.B., K.C.M.G., C.V.O., D.S.O., the man now in charge of Dublin, was to say later—“saw red.”

Love Irish history? Share your favorite stories with other history buffs in the IrishCentral History Facebook group.

“Possibly unfortunate incidents,” stated Maxwell after the rebellion, “which we should regret now, may have occurred. It did not, perhaps, always follow where shots were fired from a particular house the inmates were always necessarily aware of it or guilty, but how were the soldiers to discriminate? They saw their comrades killed beside them by hidden and treacherous assailants, and it is even possible that under the horrors of this peculiar attack some of them ‘saw red.’ ” Translated into English: it’s okay to shoot first and ask questions later.

The rebels played fair in the dirty game of war—and the British couldn’t stomach it. Maxwell was obviously looking for an excuse for his men’s immoral actions. Captain R.K. Bereton, J.P., who was a prisoner of the Volunteers in the Four Courts the whole of Easter Week defended his captors: “What impressed me most was the international tone adopted by the Sinn Féin officers. They were not out for massacre, for burning or for loot. They were out for war, observing all the rules of civilized warfare and fighting clean. So far as I saw they fought like gentlemen. They had possession of the restaurant in the [Four] Courts, stocked with spirits and champagne and other wines, yet there were no signs of drinking. I was informed that they were all total abstainers. They treated their prisoners with the utmost courtesy and consideration, in fact they proved by their conduct that they were men of education incapable of acts of brutality.”

Herbert Henry Asquith, the British Prime Minister, also disagreed with Maxwell, the man he sent to Dublin to put down the Rising and who would hurriedly shoot 15 rebel leaders in nine days: “So far as the great body of insurgents are concerned, I have no hesitation in saying in public they conducted themselves with a humanity which contrasted very much to their advantage with some of the so-called civilized enemies which we are fighting in Europe. That admission I gladly make, and the House will gladly hear it, they were young men, often lads. They were misled almost unconsciously I believe, into this terrible business. They fought very bravely and did not resort to outrage.”

The British Advance on North King Street

The British came down Bolton Street to advance a rearguard action on the Four Courts. Bolton Street swings into North King Street and this is where the rebels made their stand. The British were held off by Volunteer snipers. It soon became a matter of house-to-house combat.

Acting more like Nazi SS-Einsatzgruppen slaughtering Jews in Eastern Europe in 1941 than regular army soldiers, the British forced their way into buildings where terrified civilians were hiding in fear of their lives. In each instance, they separated the men from the women and brought the men to a different part of the house to be executed. Here are two eyewitness accounts of the atrocities perpetrated at 27 North King Street by His Majesty’s Army as revealed at the Coroner’s Inquest in May 1916:

27 North King Street (Louth Dairy). Victims: Peter (Peadar) Joseph Lawless (age 21), James McCartney (age 36), James Finnigan (age 40), Patrick Hoey (age 25).

Inside the GPO after the 1916 Easter Rising.

This is the powerful eyewitness statement of Mrs. Mary McCartney, widow of James McCartney. Mrs. McCartney was the employer of my Aunt Kathleen, the “maidservant, Catherine McEvoy,” and reveals the key role Kathleen plays in this declaration:

Myself, Mr. McCartney, and our baby only a few weeks old went over to Mrs. Lawless’s, 27 North King Street, in Easter Week. We were accompanied by a maidservant, Catherine McEvoy. The Lawless’s were very old friends of ours and I thought we might be safer there. I had been only twenty months married.

On Saturday morning when the military came about 8 o’clock things were very quiet and we thought the fighting was nearly all over. The military, who rushed in, were a savage brutal crew, a disgrace to mankind. An ignorant sergeant, who seemed to be in command, seemed particularly cruel and would listen to no explanation.

As we stood lined up in the top room, the sergeant accused the men of firing from the top of the house. Mrs. Lawless spoke up to them, and asked, “How could the men fire when they had no arms or ammunition?” His only reply was a brutal laugh, and “Where have you hid them?” He was also asked how could the men get back when the military surrounded the house and where there was no fanlight or skylight. Pointing to a bullet rip in his hat he said “How did I get that?”

Mr. McCartney said, “I could certify that I have nothing to do with the organization,” and gave the name of a friend of his, a Captain Irwin of the Recruiting Office in Brunswick Street as a reference. Poor Mr. Finnigan said, “I have never carried arms in my life.” I was terrified, screamed, and was almost fainting with terror. Poor young Lawless, who had known me for years, said, “Don’t cry, Mary,” and tried to comfort me. He would say, “Can’t you stop crying, the men will do you no harm.” But the soldiers forced us away from them.

It was, although we could not believe it, a last parting on this earth. As we went downstairs I sat for a moment in the room below, sick with terror. I thought of the keys, and asked the maid to go back upstairs to Mr. McCartney to get them. When she went up the soldier savagely snapped the keys from my husband’s hands, gave them to the maid and hurriedly thrust her away.

The men had now become terrified at the foul demeanor of the soldiers. Evidently, they were now intent on their bloody purpose and were determined to show no mercy, for the girl heard one of the men in the room say, “O my God! What are they going to do with us?”

I can never for one moment believe that any of those soldiers really thought that the men had fired on them. My poor husband’s watch was stolen, also a safety razor which he carried with him. He had marked a sovereign which he kept as a keepsake to be given to his infant child in later years. It also was stolen. A diamond pin only, a present which his employer’s wife, Lady Gallagher, had made him when he was appointed manager, was found upon his body.

As his life’s blood had trickled over it doubtless it escaped the covetous eyes of his executioners. One of the soldiers was afterward heard to say “The little man made a great struggle for his life and tried to throw himself out of the window, but we got him.”

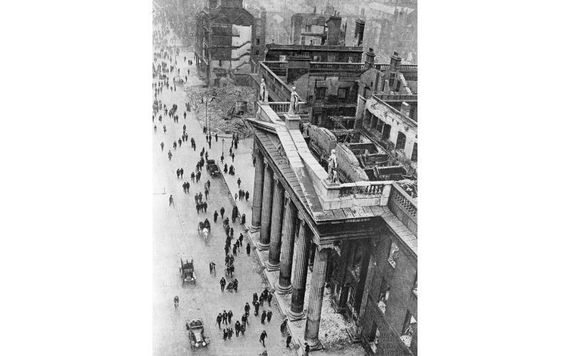

An aerial view of the GPO after the 1916 Easter Rising.

The following statement from Mrs. May Lawless also mentions my Aunt Kathleen and basically substantiates Mrs. McCartney’s statement, but adds more savage details:

My son. Peter Lawless, was 21 years of age, and was born in New York, and was consequently a citizen of the United States. During Easter Week I occupied the house No. 27 North King Street, known as the “Louth Dairy.” My son assisted me in the business.

The military came to our house the latest in the street—between 8 and 9 a.m. Saturday morning. At that time they must have had already slaughtered the nine poor unoffending people in the houses opposite my house.

On the Saturday the shop was closed and the following people were in the house: Two old friends of mine, Mr. James McCartney, who was manager of Gallagher's tobacco store in Dame Street, and his wife with her baby three weeks old, and accompanied by their maid, a girl named Catherine McEvoy. My son Peter Lawless was there also, and two tenants of mine who lived in the house, bread car drivers, employed in Brennan's of Dorset Street; James Finnigan, and Patrick Hoey. Mr. and Mrs. McCartney had come over from their place in Exchange Street, thinking they would be safer in my house.

We had been sitting on the stairs for safety during the night, and when the morning of Saturday came the firing seemed to have ceased and we went upstairs thinking of going to bed. Just then, about 8 a.m. (Saturday) we heard a great hammering and knocking at the door and the soldiers shouting outside. Soon a bayonet was thrust through the panel of the hall door. At length, I heard my son below opening the door which was followed by the inrush of the soldiers. I heard my son saying, “Mother, you all go upstairs to the top room, these men are only doing their duty, you need not be frightened.”

The four men were then driven up after us with their hands above their heads by the soldiers. The soldiers then lined us all around the walls of the room with hands up. They then proceeded to search the men. I asked them “What are we here for? What have we done?” The man in charge replied, “We must take these men prisoners.” I said, “Where are you going to take them?” “To the nearest barracks, I suppose,” he replied. Someone then said, “That is all right, the police will then tell you who we are.” I remember poor McCartney mentioned the name of some military captain of his acquaintance who could identify him.

We women, who were in great terror, were then ordered out in charge of some soldiers. As I passed out my poor son, who stood near the door, came out on the landing to try and reassure me, and said, “Mother, it will be all right. You go to Britain Street. I’ll find you there.”

It was the last I saw of my poor son alive. It was then about 8.30 a.m. The soldiers then brought us down to a cottage in Linenhall Street a few doors off, where we stayed during the day. As I left the house I heard shots, for I remarked at the time, “Are you going to put us out in the street in that shooting?” But I cannot be certain whether the sounds came from the house.

In the evening, about half-past seven, I returned to our house accompanied by a soldier. A sentry was on guard at my door (No. 27), and as I attempted to go in he said, “You can’t go in there.” I said, “Why cannot I go in there? Can’t I go into my own house?” “Well,” he said, “there are four dead men in there.” Terrified, I said, “Four dead men! Are they soldiers or Volunteers?” He replied, “Neither, civilians.”

I then said, “I left four men there, and I’m going in to see. If you [shot] them, you may shoot me too.” I then shoved past him, and the soldier who came with me from Linenhall Street accompanied me to the top landing. And then a scene of horror met my eyes. My son lay dead in the same spot I had left him—on the landing of the top-back room, his body half in and half out the doorway. Poor Mr. McCartney lay dead against the wall in a sitting position. Their brains had bespattered the curtains. Poor Finnigan was in the same relative position but had fallen dead across the bed. Patrick Hoey was out of his old place where I had left him, but he must have received fearful treatment as his head was burst open and macerated.

I was overcome with horror. I went to Ann Street Presbytery where the priests kept us all night. On Sunday morning the soldiers refused admission to the clergy as no doubt they feared that their foul deed might see the light of day. The soldiers buried the four bodies in the yard of the house and replaced the tiles over the grave. They then burned the clothes of the bed, as well as the curtains, in the yard. They were seen burning and smoldering by several of the neighbors. The remains of all were discovered on Monday morning and buried by us.

**For more North King Street witness statements before the Coroner’s Court click HERE.

The leader of these soldiers was Lieutenant-Colonel H. Taylor, commanding 2nd/6th South Staffords. He couldn’t be bothered to show up to the inquests. Instead, he sent along a self-serving statement about how badly hurt his men had been by the rebel snipers. According to him, his men had murdered no one. In conclusion, he said, “I am satisfied that during these operations the troops under my command showed great moderation and restraint under exceptionally difficult and trying circumstances.”

Fifteen dead innocent Dublin men and no one to blame. It was British Law and Disorder at its best. It would continue in Ireland until 1922 and return again to the North 50 years later in the form of Bloody Sunday 1972 when 13 more innocents were slaughtered by the British army. It took almost 40 years, but at least this time the British admitted to their crimes, courtesy of the Saville Inquiry. To this day, as my Aunt Kathleen knew, the presence of British troops in Ireland is a recipe for disaster—especially for the Irish.

* Dermot McEvoy is the author of the The 13th Apostle: A Novel of a Dublin Family, Michael Collins, and the Irish Uprising and Irish Miscellany (Skyhorse Publishing). He may be reached at [email protected]. Follow him at www.dermotmcevoy.com. Follow The 13th Apostle on Facebook at www.facebook.com/13thApostleMcEvoy.

** Originally published in 2016, updated in 2025.

Comments