Oscar Wilde was a child at the time of the American Civil War; he was just eleven when the war ended in 1865. But there are intriguing connections.

The Wilde household in Dublin would have taken a keen interest in the Civil War. As a fervent nationalist, Oscar's mother, (Lady) Jane Wilde (the illustrious “Speranza”), no doubt followed the war closely.

But she also had personal reasons. Her brother, John Kingsbury Elgee was a prominent lawyer and judge in Louisiana. He was a slave-holder and an ardent supporter of the Confederate cause. In fact, he was a signatory to Louisiana's Declaration of Succession at the start of the war.

His son, Charles LeDoux Elgee (first cousin to Oscar), was a captain in the Confederacy army. He would see action, be captured and imprisoned, dying of fever before the war ended.

Even without the family connections, Jane's sympathies would probably have been with the Confederate side, seeing parallels between the Southern cause and that of the Irish struggle for independence.

Read more: Irish housekeeper of the Confederate White House

Lady Jane Wilde. Image; Public Domain/Wikicommons.

In 1881 when 27-year-old Wilde set out on his American lecture tour, the Civil War had been over for 16 years. But many issues remained raw and unresolved, particularly in the South. Wilde was not known for his nationalistic views, but astonishingly, he now expresses strong pro-Confederacy views, to the point of justifying the South's stance in the Civil War.

He calls it “a great cause” and says, “The principles for which … the South went to war cannot suffer defeat.” He characterizes the Civil War as the South's struggle for self-rule and compares it to that of Ireland.

“We in Ireland are fighting for the principle … for which the South fought.”

These views resonate with many Southerners and receive wide reportage. But it's not certain how deep-rooted or sincere these sentiments were on Wilde's part. This, after all, was a publicity tour, and such views were guaranteed wide-spread coverage, particularly in the South.

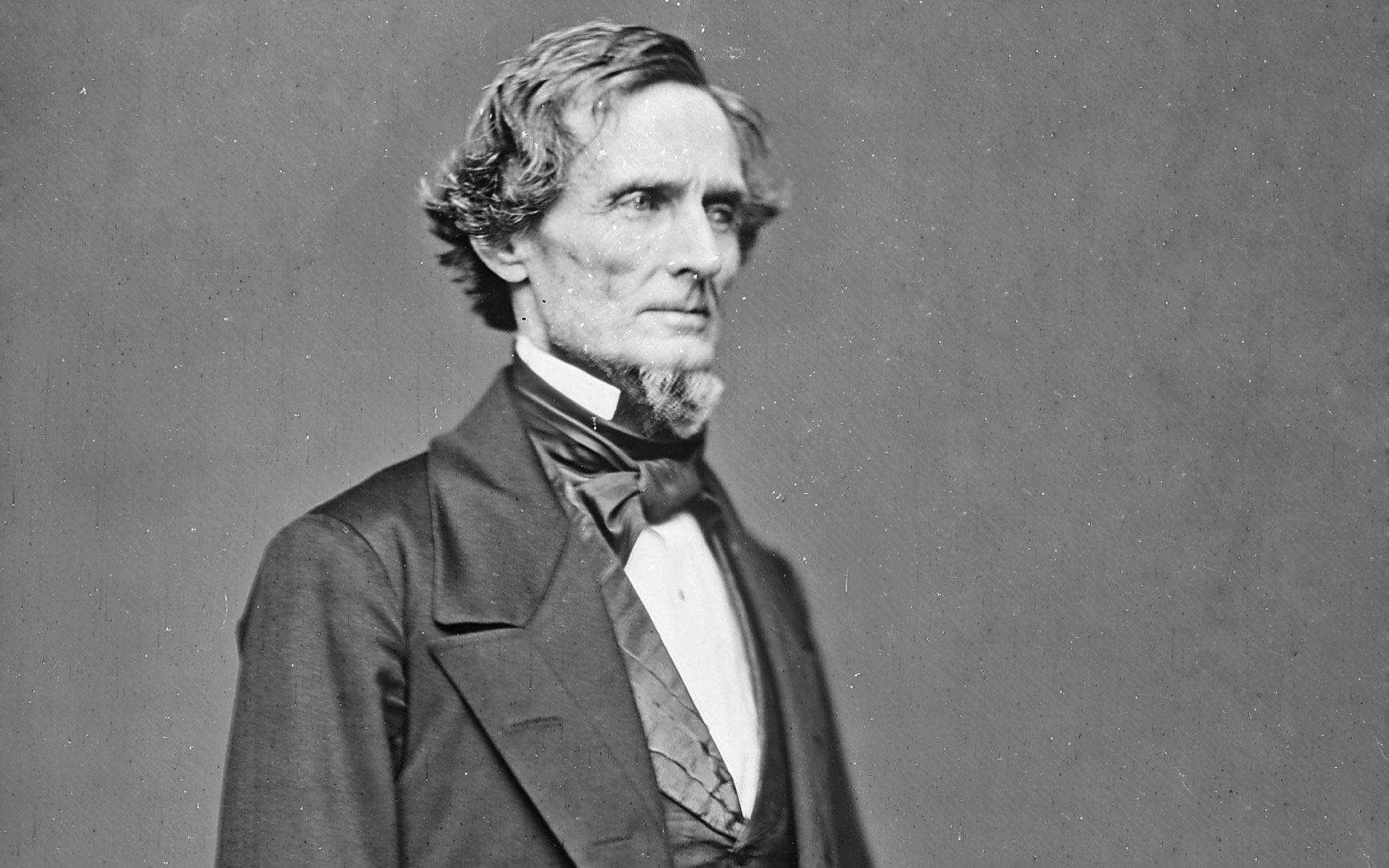

Wilde went further. The one American, he says, that he would like to meet most is Jefferson Davis, the former president of the Confederacy. He speaks in glowing terms of Davis, praising his views and portraying Davis as a great hero of his.

Read more: The Irish woman who worked as a nanny for Confederate leader Jefferson Davis

Jefferson Davis in 1861. Image: Public Domain/WikiCommons.

Jefferson Davis had long outlived his rival president, Abraham Lincoln. After the war, he avoided execution, serving just two years in prison. He was now living in Biloxi, Mississippi with his wife and teenage daughter. He remained an unrepentant defender of the Confederacy cause, racism, white supremacy and all.

Davis had written a massive personal history of the war entitled "Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government." Its reception was mixed, many finding it tough going. However, Wilde now hails it as a masterpiece (but admits that he hadn't actually read it all).

Further stretching credulity, it was reported that he kept a copy by his bedside. Wilde announces he wants to make a “pilgrimage” to the Davis home and writes to him for an invite so he can pay homage.

Whether this talk of pilgrimage and homage was simply a publicity ploy or not, Wilde had a genuine reason to visit Davis. The Wilde family knew Davis, or at least had corresponded with him. In 1870, when Davis visited Dublin, Jane invited him to visit the Wildes in their Merrion Square home. But Davis couldn't make it and sent his sincere regrets (on Gresham Hotel stationery) apologizing that his schedule did not allow him “pay his respects in person to the Sister of his friend the late Judge Elgee. It would have given him great pleasure to have called on Sir William [Wilde].”

Oscar Wilde.

In any event, Oscar was invited to spend a night with the Davis family on June 27, 1882. But the meeting between the long-haired “Apostle of Aestheticism,” and the austere 74-year-old, was never going to be plain sailing. “It's like a butterfly making a formal visit to an eagle,” is how a local newspaper described it.

When they meet, Davis was courteous to Wilde but remained aloof. He spoke little at the dinner table before he retired early to bed, claiming a slight illness. But the real reason was probably starker; he was uncomfortable with Wilde, possibly glimpsing a new world that was alien to him. He saw something "indefinably objectionable" in Wilde. Later he would bluntly tell his wife, “I did not like the man.”

On his departure next morning, Wilde left a photograph of himself (in fur-lined coat and velvet jacket) for Davis. It was inscribed, "To Jefferson Davis in all loyal admiration from Oscar Wilde...”

But Davis wasn't impressed; he considered it presumptuous. Although Wilde's admiration for Davis seems genuine (later describing Davis as a man of the “keenest intellect”), perhaps his subsequent description of Davis as a fascinating failure is closer to his true feelings towards him.

But Wilde lit a fire that evening in Biloxi. When Davis departed the dinner table early, he left behind three literary and lively women; his wife Varina, his daughter “Winnie” and a visiting cousin, Mary Davis. And we can almost visualize the whole atmosphere at the dinner table transforming. Wilde came to life; he "brightened perceptibly and charmed the three ladies beyond words." They were enchanted by him. The four talked till after midnight. He inscribed a copy of his poetry to Mrs. Davis (“...in memory of a charming day....”); she did a pencil sketch of him (with a decidedly androgynous look). The visiting cousin Mary admits to being enraptured by Wilde, writing later that she would never be mentally free of his charms. But the biggest impact was on the third woman; daughter, Winnie.

Read more: Most of 40,000 Irish who fought for the Confederacy were not fighting for slavery says historian

Portrait of Varina Anne "Winnie" Davis, by John P. Walker. Image: Public Domain/WikiCommons.

It was Winnie's eighteenth birthday that evening (what a dinner guest for your eighteenth birthday!). She had been educated in Europe and was well versed in European and Irish history. She was an aspiring writer (or at least was after this evening) who would later become an icon for Confederate veterans, and acquire the title "Daughter of the Confederacy."

The conversation that night was no doubt literary. But it was also of politics. They would have spoken of the two great Lost Causes; of Ireland and of the South, drawing parallels – as Wilde had done earlier – between them, and the fate they now shared.

Miss Varina Anne (Winnie) Davis, the daughter of the Confederacy. Image: Public Domain/WikiCommons.

And they would have spoken of Robert Emmet, the romantic hero of iconic status in Irish history. The Davis family believed (mistakenly, as the research now shows) that Varina's grandfather had fought with Emmet in his ill-fated resurrection of 1803. Wilde admired Emmet, had spoken of him and met his descendants earlier in the tour.

So it's not surprising if a seed was sown in Winnie's mind that would see her subsequently write a biography of Emmet. Almost certainly Winnie saw similarities between her father and Emmet, both noble martyrs in her mind. The short biography echoes the language and symbolism of the South's Lost Cause. And it echoes a theme that Wilde had raised; the similarities between Ireland and the Confederate South. The title –– “An Irish Knight of the 19th Century” –– is surely a nod to Wilde.

The book is not a comprehensive biography of Emmet; more a romanticized hagiography. But it is important. It was published to some acclaim in 1888 and achieved popularity, particularly amongst Irish Americans. It was passed around many Irish societies in America and was said to have “awakened much enthusiasm.” It has been credited with fostering interest in Emmet in the United States, which is alive to this day.

Robert Emmet by William Read. Image: WikiCommons.

Winnie's short, woe-filled life had parallels with Wilde. Like him, she became a very modern entity – a celebrity. Being photogenic and from a famous family, the public found her intriguing. And the press responded. Her every move was reported, particularly any hint of scandal or gossip. Her image was used liberally in advertising posters, seemingly without her consent.

Her one true romance ended in bitter farce; he was a Northerner and public disapproval proved overwhelming. She died unmarried, age thirty-four in 1898; a year after Wilde's release from prison and two years short of the new century that perhaps both would have been more in tune with.

Frank Burns (@TwoCatherines) lives in Dublin and is the author of "The Two Catherines," an extraordinary true story from the American Civil War: https://t.co/yz0osEf9hW

Comments