Douglas Hyde was a thoroughly modern figure for a modern Ireland: a non-Catholic but staunch defender of the preservation of the Irish language and of the country’s cultural heritage.

Douglas Hyde was a thoroughly modern figure for a modern Ireland: a non-Catholic but staunch defender of the preservation of the Irish language and of the country’s cultural heritage.

Hyde was born in Castlerea, County Roscommon, in 1860, though he spent his early years in Sligo where his father was a Church of Ireland rector, in Kilmactranny.

Read more: Book Review - "Douglas Hyde, My American Journey"

Hyde's education

The family moved to Frenchpark, County Roscommon when Hyde was seven and he was homeschooled by his father and aunt due to a childhood illness. Even while young, he was interested in older people in his locality speaking Irish, being particularly influenced by gamekeeper Seamus Hart. He also studied an Irish language New Testament belonging to his father. Though Hart died and Hyde’s interest in the language diminished as he aged, it was to revive when he visited Dublin and realized there were many who were as equally enthralled.

He was expected to follow his father into religious life but Hyde preferred to choose an academic path. An impressive polyglot, he graduated from Trinity College Dublin in 1884 as a moderator in modern literature – and fluent in French, German, Latin, Hebrew, and Greek. A brilliant student, he won the Gold Medal for Modern Literature for his language ability and later returned to the university to study law and divinity. However, his first love remained languages.

Passion for Gaelige

His passion for Irish had also not abated despite his studies. He joined the Society for the Preservation of the Irish Language around 1880 and within five years, he had published over one hundred pieces of Irish verse under the pseudonym An Craoibhín Aoibhinn (The Pleasant Little Branch). The movement gained an impressive following, helped no doubt by Hyde’s actions. He also collaborated with many of the Celtic Revival writers including W.B .Yeats. In fact, Yeats championed Hyde as a driving force to put Irish literature and folklore on an international stage.

Read more: Honoring how America helped the survival of the Irish language

Keen to preserve and develop the love of Irish, Hyde published bilingual anthologies Beside the Fire (1890) and Love Songs of Connaught (1893) as well as A Literary History of Ireland (1899). All are believed to have heavily influenced Irish literature and folklore studies. Other works include Legends of Saints and Sinners (1915) and The Bursting of the Bubble and Other Irish Plays (1905).

He helped establish the Gaelic Journal in 1892 and that November, wrote The necessity for de-anglicizing the Irish nation, a manifesto that Ireland should adhere to its own language, literature and dress traditions.

But it was his involvement with the establishment of Conradh na Gaeilge (the Gaelic League) in 1893 to encourage the preservation of Irish culture that was of most significance. The League was open to those of all religions and in name, was non-political though it became an influential organization for people such as Michael Collins and Padráig Pearse. The League organized classes and competitions in Gaelic music, games, and dancing and also encouraged Irish industry.

Pearse wrote that: “The Gaelic League will be recognized in history as the most revolutionary influence that ever came into Ireland. The Irish Revolution really began when the seven proto-Gaelic Leaguers met in O’Connell Street… the germ of all future Irish history was in that back room.”

Fight for education

At the turn of the 20th century, Hyde led a successful battle to prevent the exclusion of Irish from the secondary school curriculum, something that was furthered when he helped to make Irish a compulsory subject for matriculation at the National University of Ireland, where he had been appointed professor of modern Irish in 1908. He would hold that position until 1932. By 1903, when the League had an estimated 550 branches across Ireland, it formed its first training college for Irish teachers, Coláiste na Mumhan, in Cork.

Not that developing the appreciation of the Irish language was fully embraced or that Hyde had an easy time. In later life, he spoke about a conversation with a young boy in County Sligo and being answered in English. When Hyde asked him in Irish why he wasn’t speaking Irish, the boy replied in English: “Sure amn’t I speaking to you in Irish?”

While the League grew in popularity, it became increasingly identified with political goals. In 1915 a motion was passed making an independent Ireland one of its goals. Uncomfortable at the politicization of the movement, Hyde resigned his presidency in 1915 and was succeeded by his League co-founder, Eoin MacNeill.

Life in politics

After a brief election – and elimination – from Seanead Éireann in the mid-1920s, he returned to academia as Professor of Irish at University College Dublin. Less than 15 years later, Éamon de Valera, then Taoiseach, appointed the retired Hyde to the Seanead. His tenure proved shorter than his first but this time, it was because he’d been chosen as the first President of Ireland, a role to which he was elected unopposed. His appointment seemed apt: both de Valera and Leader of the Opposition W.T. Cosgrave saw Hyde as a man with universal prestige who could lend credibility to the new office. Both also wanted to pay tribute to his role in promoting the Irish language. Moreover, at a time when the new 1937 Constitution made it unclear whether the President or British monarch was head of state, de Valera and Cosgrave wanted someone who would not become an authoritarian dictator in the country.

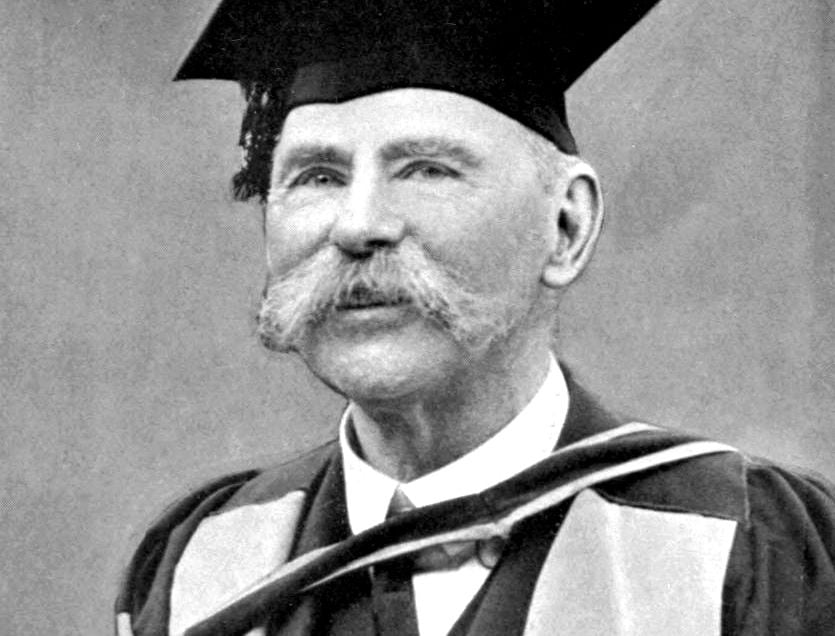

Douglas Hyde, Ireland's first president.

He was inaugurated on June 26, 1938. The Irish Times described the evening ceremony in Dublin Castle as: “…the most colorful event that has been held in Dublin since the inauguration of the new order in Ireland, and the gathering, representing as it did every shade of political, religious, and social opinion in Eire, might be regarded as a microcosm of the new Ireland.”

His inauguration received international attention but the Northern Ireland Finance Minister John Miller Andrews described it as ‘a slight on the king’ and a ‘deplorable tragedy.’

Read more: Why Douglas Hyde, not the "Lord Mayor of Ireland," became Ireland's first President

Ireland's first president

His was a quiet presidency despite being best placed to shape the office. His lack of political experience led to him deferring to his advisers, especially his secretary Michael McDunphy. After just a few months of being president, he was removed as patron of the GAA – which he had held since 1902 – after attending an international soccer match between Ireland and Poland at Dublin’s Dalymount Park. Poor health – he had a paralyzing stroke in April 1940 – obligated him to have daily rest periods.

Although the role was largely ceremonial, he had to make some decisions that affected the country. In 1944 when de Valera’s government collapsed over a vote on the Transport Bill, Hyde had to decide whether or not to grant the Taoiseach an election. Twice he invoked the presidential power under Article 26 to refer proposed legislation to the Supreme Court. One of his final acts, though it was kept secret for six decades, was to offer Ireland’s condolences to the German ambassador on Hitler’s death.

He left office in June 1945, choosing not to nominate himself for a second term. He moved into the former Secretary to the Lord Lieutenant’s residence in the grounds of Áras an Uachtaráin, which he renamed Little Ratra (Ratra being his Roscommon home). He died on July 12, 1949, aged 89. He was given a state funeral and is buried beside wife Lucy, daughter Nuala, sister Annette and his parents.

A Gaeilgeoir, academic and poet, Hyde’s work in reviving the Irish language plus his contribution to the formation of the Irish identity cannot be underestimated.

Love Irish history? Share your favorite stories with other history buffs in the IrishCentral History Facebook group.

Comments