Death comes for everyone eventually; it loudly announced its plan for my grandfather. After a remarkably quick battle with cancer he died in his sleep at 5:30 a.m., January 1, 1997. It was shocking how quickly his physical presence was removed from our lives. He was my father’s father and his death changed the order of our family. My father was now the head of the family; I became the next closest “heir.” We were now left alone with a pain so great it was almost impossible to soothe each other. This pain was the only physical remnant of my grandfather; it was all I had left. In a way I was afraid to let it go, I didn’t know what would be left for me.

My grandfather, John William Mulherin, was born on April 21, 1913 in County Mayo, a poor farming county on the West coast of Ireland. He was the middle child of an arranged marriage and his short childhood in Ireland was soaked in alcohol and ripped apart by violence. He eventually had six siblings, but never much of a family. His youth in Ireland taught him that a family was just a group of individuals you lived with, not much more.

When he was fifteen he was moved to America and never saw his parents or three of his siblings again. As far as anyone in America knew at the time, he never wanted to. Ireland was not part of his family, he wanted to make his own and never look back.

Many forces shaped my grandfather’s childhood - alcoholism, poverty and depression were a few of the obstacles impossible to overcome. His father was a troubled alcoholic who eventually drank away their farm and abused his wife and children. One night in a drunken rage his father held a knife to his mother’s very pregnant stomach and threatened to slice it open in front of all the children. My grandfather never knew why. Such violence was spread around to every family member over time.

The tiny, two-room stone cottage in the middle of the sheep was far from everything but the children’s school. That was fortunate because they rarely had shoes to walk the stony, dirt road to school. Farming in Ireland, under the Empire of Britain, was rarely profitable for tenant farmers and his family was no exception. Combined with the drinking they didn’t stand a chance.

By the time my grandfather was 13, what little money his family had was gone and their farm was foreclosed. The date was set for auction but his father was too drunk to attend and his mother refused. My grandfather was sent as the family representative and stood in the back of the smoky room.

I imagine this handsome young boy, towered over by rough, strong arms and drowned out by harsh voices. He watched as his home sold to the highest bidder. He walked back the way he came and told his parents their home had been sold. Soon after, the Division of Social Services came to help the children and sent them to relatives who would take them.

His mother found relatives in London that were willing to take my grandfather and his younger sister, Nellie. They were sent by boat to live with the Kilgallons and what passed for a childhood was over.

After a terrible incident of abuse, my grandfather was sent to America and Nellie was sent to Dublin. They adored each other and looked so similar they could have been twins. She was a beautiful young girl with curly blonde hair and green eyes. Her smile was uplifting and contagious and she loved to wear ribbons in her hair.

He was a striking young man with slight wavy hair, crystal blue eyes and ruddy Irish skin. Their personalities were almost identical as well and they had been happy to have each other, it made their time in London more bearable. He was 15 and Nellie was 11 when they were separated, but she knew she would see him again, hopefully soon.

Nellie returned to Ireland, but she missed her brother. She felt sorry for him, she said, going all the way to America alone, but what could she do? He was going to be with recently emigrated relatives and hopefully their lives would be better. Hopefully, she thought, they would both finally find peace.

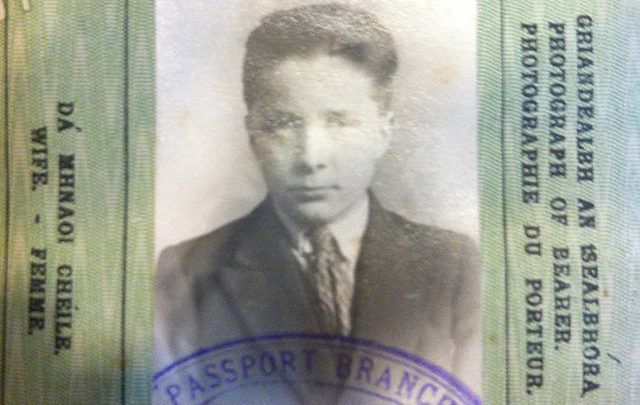

America was the land of opportunity for my grandfather, but only because he worked and struggled on his own. His American relatives seemed as bad as their European counterparts. Due to the abuse in London, he has two black eyes on his passport photo. His last name was misspelled on his passport; inserting an “I” changing the name to Mulherin.

He spent three days on Ellis Island before being discovered by another immigrant. After being interviewed by a Probate Judge in New York who contacted his sponsor, he traveled alone on a train to Chicago. His uncle Kilgallon made him sleep in the basement and locked the pantry every night so he would not take more than his share of food.

His uncle got him a job delivering bags of flour in the dead of summer. Every morning he would wake at dawn and walk to the neighborhood dock. There he was given various sizes of bags of flour and he would deliver them to private homes or small stores. From early morning to dusk he carried 15 or 20 pounds of flour in rough burlap sacks in the sweltering summer heat.

He returned to his uncle’s every night like a gritty, fatigued ghost only to repeat himself the next day. It was demanding physical labor for a child. He knew education was his way out, so after working 10-hour days he went to night school to earn his high school diploma.

Every night he went to school and sat in the front row. He loved it and soaked up the atmosphere and all the knowledge he could. He loved the smells of the building; of chalk, coffee and wood. He loved how warm it felt at night and how others in his class struggled, but learned to read and write well.

He belonged there with those students, all of them working hard to change their lives. The struggle there was never as hard as the struggle at home or as tough as wrestling a bag of flour.

His citizenship and diploma offered him a chance for a new place and home in America. He vowed he would do whatever he could so his family could have the best education he could afford. He graduated with honors. He lost his brogue. He fell in love.

He met a young, beautiful blonde woman in her early twenties at a swimming party at Hudson Lake, Indiana. She was happy and fun to talk with and they got along well enough. He proposed to her a few years later, but did not want to get married until he had a job and some security. He was eager to start a family and settle down but work was hard to find. That winter he scheduled an interview at Brandywine Mattress Company at 12th and Ashland in Chicago for the position of salesperson. He didn’t have much experience but thought he had a chance as a salesman. He was charming, persistent and hard working. He just needed to show them that.

The day of the interview a blizzard hit Chicago and the streetcars stopped running by mid-morning. He lived at 61st and Ashland and was determined to get to his afternoon interview, so he walked the 49 blocks and arrived early for his interview. The furniture company had sent most of their staff home early because of the snow but a head salesman was still there working when my grandfather arrived.

“Can I help you?” he asked.

“I’m here for an interview for the sales position,” he told him, his face red from the wind and his bones almost frozen.

“Well, there aren’t many people left today. How did you get here?”

“I walked,” my grandfather said.

“Anybody who makes it here in these conditions deserves to be seen. Have a seat.”

My grandfather sat and waited to see another sales person, and he left with the job. The next summer my grandfather and grandmother were married. The following year they had a son, my father, John Michael. My grandfather worked hard at his job and enjoyed working with customers and providing for his family. He loved my father as any parent would, but just a bit more, I believe.

One birthday he asked my father what he wanted and he told him, “a yard.” The next year they moved to a house on the South Side in the Beverly neighborhood, and my father got his wish.

Physical surroundings and security gave him some comfort, but my grandfather still struggled. He loved my father with all his being but could not change his own behavior. He drank heavily until my father was a college student. My grandmother drank, too, and their marriage was a troubled as his parents, without the violence. As my father grew they became more estranged and had no other children. They had bitter fights that eventually dissolved into a fierce truce.

Silence was deafening in my father’s home as a child. No long distance family was ever discussed. My father knew his father was from Ireland and that he’d had a rough childhood ,but the full story did not come out until years later. My grandfather was still drinking when news came from Ireland that his mother had died.

My father took the message and told my grandfather himself. He gave no outward response to the news. He hadn’t spoken to any of his Irish family for over 25 years. What could his siblings give him now? It had been too much time and distance. He was a different person now.

He never spoke of Ireland, never celebrated Irish holidays, was a lapsed Catholic and proud to be an American. Ireland held no romance for him. If he didn’t talk about his past, it couldn’t intrude on his present. Troubled as it was at times, he fought for his new life and he wanted to stay free. He was proud of his life, one he had worked hard to make his own. And his son, he was very proud of his son.

My father wanted my grandfather to be free from alcohol. He wanted a father who would live a long life and be happy. He was always proud of him, but the darkness and isolation of alcoholism prevented both of them from enjoying his life and finding peace.

My grandfather worked hard to put my father through college and wanted him to become a lawyer. His passion for education and his vow to give his children the best had never subsided. He wanted prosperity and security for his son; my father was accepted at Northwestern Law School and my grandfather wanted him to attend. My father wanted to be a journalist and it was one of the few times they really fought.

My father made him a deal. “I’ll go to Northwestern…if you stop drinking.”

My father became a lawyer and my grandfather never took another drink.

My grandmother died in the early 1980's when my grandfather was in his late 60's. After his marriage to my Lutheran grandmother, he gave up the Catholic Church. It didn’t seem important to him then but after his mother’s death he had a nagging desire to return. He discussed it with my father, who encouraged him to call his local priest. He and the priest met one crisp, sunny fall Saturday afternoon and the next Sunday my grandfather was at 7:00 a.m. mass. It was a difficult decision to make but it was one of the best things he ever did.

He was not very religious, but the church was his salvation. Through it he made a new group of friends and a social network so extensive my father and I had no idea he was in the Kiawanas volunteer organization until after his death.

By the early 1990s my grandfather settled into a routine that kept him busy every day of the week. He worked out four mornings a week, played golf every Wednesday and worked five full days a week. He ushered 7:00 a.m. mass every Sunday and had marathon breakfasts afterward with the priest and close friends. He loved waking up every day at dawn, talked with my father every night and cherished his relationship with me. He was the happiest he had ever been.

In 1993 his sister Una died and the funeral mass was videotaped, according to the Priest. “for Una’s brother in Chicaaago” using the common Irish pronunciation for Chicago. Relatives who had tentatively and gradually increased contact with us American cousins over the past years sent us a tape of the funeral mass and the three of us watched it together.

After 66 years of age my grandfather saw his sister Nellie again, on shadowy, grainy videotape. My father gently suggested they go to Ireland soon. My grandfather silently nodded. He didn’t know if he could face it. It had been so long that he knew his neighbors better.

“I’d like to go, Dad,” my father said. “They’re my family, too.” That was the last push by my father.

My grandfather left that night without making a commitment to my father. I remember my own father sighing, wishing for a chance to return and see his own family.

About an hour later the phone rang, it was my grandfather. “Buy the tickets,” he said to my dad and that was all my father needed to hear; they were heading home.

On a cool, foggy misty Irish morning in October, 1994 my grandfather and father landed at Shannon Airport. A group of 20 plus immediate family met them, including his sister Nellie.

As they witnessed the Aer Lingus jet land, Nellie said, with tears of happiness running down her cheeks, “He’s on Irish soil again.” Shortly thereafter my grandfather saw his sister and his brother Tom for the first time in 65 years; they ran into each other arms and cried pure tears of joy.

The family resemblance was still strong. Nellie and he looked more alike than ever, age had not diminished that. They could not stop hugging, laughing and crying, overcome by their emotions. Relatives were discovered and new connections were made.

My father looked like his cousins and I looked like their children, mannerisms were the same and laughter was contagious. It felt like a parallel universe existed all those years and they mutually discovered it. It was more family than my father had ever seen in his life and it was the warmest group he ever met. It was home.

“I’ve lived a blessed life,” my grandfather told me shortly before his own death. “If I die tomorrow, I will die a truly happy man.”

November, 1996, my grandfather was diagnosed with stage-N colon cancer. The young intern told me what that meant and I called my father to tell him. It meant it had spread to a point where there was no hope of recovery. Our rediscovered family was informed and a global network centered on my grandfather’s hospital room. Constant phone calls came from Nellie before he died and I was there for many of them. She could not stop crying, trying to squeeze in time with the lost brother she recently found.

“She’s crying,” he would say, cupping his hand across the beige hospital phone, “but, oh, isn’t she wonderful?”

Two years after my grandfather died my father took my sister, Kelly, and me to Ireland. We were still healing, learning to live with the grief. We visited Nellie and her husband, Leo, outside Dublin at the end of our trip.

“I never thought I’d be the last to go,” she said while cooking a feast of monstrous proportions. She was spry, vibrant and as beautiful as my grandfather was handsome. Leo turned 90 that year and he wore his best suit for our visit. She looked and spoke like my grandfather.

I had crossed over to that parallel universe and seemed to feel my grandfather’s touch for the first time in two years. Their resemblance was so strong, I felt the loss of my grandfather all over again, fresh and painful but with an edge that was softer now.

They are my family, my aunts, uncles and cousins with a connection to me that has the strength of heredity and passion of newly found love. It was, as my grandfather would have said, the best thing I had ever done. After a long dinner we left Nellie’s house and she smiled with tears in her eyes.

“You look so much like your grandfather,” she told me with her shining eyes. “Please come and see us again. I miss him so much. But, oh, wasn’t he wonderful?”

* Originally published in 2015.

Comments