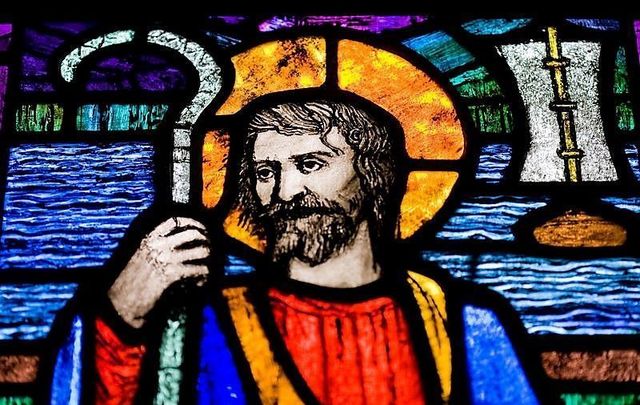

St. Patrick and paganism in Ireland - Irish author Ali Isaac explores one fascinating intersection.

Who was the Irish god Crom Cruach, what was the Killycluggin stone, and what did St. Patrick have to do with it all?

Long fascinated by the Killycluggin stone, which sits practically in my backyard in Co. Cavan, I set out to learn its story.

Sandwiched between the Woodford and Blackwater rivers lies an area of Co. Cavan known as Magh Slecht (pronounced Moy Shlokht). Overlooked by the scenic Cuilcagh Mountain and distant rounded shoulders of Sliabh an Iarainn, this panoramic vista of gently rolling countryside is packed with an unusually dense concentration of megalithic monuments, including cairns, stone rows and circles, standing stones, fort enclosures, and burial sites.

I went to meet local historian Oliver Brady, who recently assisted on an archaeological investigation of the region.

We first went to see a replica of the Killycluggin Stone, which is located on the side of the Ballyconnell - Ballinamore road only 320 yards from where it was found. The original can now be seen in the County Cavan Museum in Ballyjamesduff.

The stone’s surface is covered in simplistic scrolling designs of the Iron Age La Tene style, and, Mr. Brady suggests, was probably once richly decorated with gold and colorful paint. These carvings look somewhat like stylized faces to me, or birds, but they have never been definitively interpreted. It looked very… well… innocent and unassuming, if such a thing can be said of a stone, particularly one with such a dark and turbulent history.

This particular stone was discovered buried in the ground in pieces in 1921 by the landowner, close to the Bronze Age stone circle at Killycluggin. It is thought that originally it would have stood at the center of the stone circle, which currently consists of eighteen standing stones, many of them fallen, and has a diameter of 72 ft.

Tall trees now encircle the stones protectively, casting them into deep shadow. Moss has draped a delicate mantle of soft green over them, shielding them from sight, and brambles bristle like a guard of honor; if you didn’t know what you were looking for, you could be forgiven for missing it altogether. A fine view of Cuilcagh dominates the horizon to the north, and the two entrance stones, once proud but now recumbent, look towards the rising sun in the east.

The circle and the stone share a dark and mysterious past, according to Irish mythology, for they have been identified as the site of pagan human sacrifice and the worship of the Sun God, Crom Cruach.

Crom Cruach is also known as Crom Dubh, or Cenn Cruach, among other names. The meaning is elusive; Crom means ‘bent, crooked, or stooped’, while Cenn refers to the head, but also means ‘chief, leader’. Cruach could mean ‘bloody, gory, slaughter’ and also ‘corn-stack, heap, mound’.

We know that there was a cult that worshiped the stone heads of their patron Gods and Goddesses in other areas of Co. Cavan from finds such as the Corleck head, although nothing similar has been recorded as being found at Magh Slecht.

The ancient Irish considered the head as ‘the seat of the soul’, and warriors were said to have collected the heads of their vanquished enemies after battle as trophies. There are many tales of decapitated heads continuing to talk and impart great wisdom to the living.

The legend of Crom Cruach is a sinister one. The ancient texts of the Metrical Dindshenchas claim that the people of Ireland worshiped the God by offering up their firstborn child in return for a plentiful harvest in the coming year. The children were killed by smashing their heads on the stone idol representing Crom Cruach, and sprinkling their blood around the base. This stone idol has been identified as the Killycluggin Stone.

The manuscript describes the site as twelve companions of stone surrounding the idol Crom Cruach of gold. Other documents, such as the Annals of the Four Masters and the Lebor Gebála Érenn, confirm this, although none of them can be taken as a historically accurate record.

They also describe how Saint Patrick put an end to this practice.

The story goes that one Samhain, the High King Tigernmas and all his retinue, amounting to three-quarters of the men of Ireland, went from Tara to Magh Slecht to worship. There, St. Patrick came upon them as they knelt around the idol with their noses and foreheads pressed to the ground in devotion. They never rose to their feet, for as they prostrated themselves thus, they were, according to Christian observers, slain by their very own God. So Magh Slecht won its name, which means ‘Plain of Prostrations’.

St. Patrick destroyed the stone idol by beating it with his crozier. It broke apart, and the ‘devil’ lurking within it emerged, which Patrick immediately banished to Hell.

The Stone does, in fact, bear evidence of repeated blows with a heavy implement and was deliberately removed from its central position within the circle and buried. A sign marks the place of its long repose.

St. Patrick led the survivors to a nearby well, now known as Tober Padraig, and baptized them all into the Christian faith. He then founded his church adjacent to the well.

St. Patrick’s church still stands in the townland known as Kilnavart, from the Irish Cill na Fheart, meaning ‘church of the grave/ monument’, and indeed there is a megalithic tomb, flanked by two sentinel standing stones, no more than 275 yards from it.

The present church was constructed in 1867, replacing an older, thatched structure with clay floors. Interestingly, the church rises from the site of a prehistoric circular fort, once known as the Fossa Slecht, possibly the home of a local chieftain.

The site of the holy well, however, has sadly fallen into disuse and lies somewhere close to the church in a patch of wasteland between two houses, and to which there is currently no public access.

It is said that St. Patrick moved from the stone circle to the holy well on his knees. Whilst not far, it can’t have been an easy journey.

Although the legend surrounding this site is quite gruesome, it should be noted that this is the only mention of human sacrifice occurring in ancient Ireland according to the early literature.

There are also some conflicts within the story: Tigernmas, for example, is listed in the Annals as having reigned for 77 years from 1620 BC. If this is so, he could not have been at Magh Slecht at the same time as St. Patrick, who came to Ireland in the 5th century AD.

In addition, there is some debate over the identification of this cruel deity with the character of Crom Cruach. In some stories, he is represented as a pagan chieftain who eventually converted to the new faith, and as such was well known to St. Patrick, and even considered as his friend.

In Co. Kerry, it is told that St. Brendan asked Crom Cruach, a rich local chieftain, for help with funding the building of his church. As an ardent pagan, Crom refused but gave St Brendan his evil-tempered bull instead, in the hope it would kill the Christians. They, however, managed to tame it, and suddenly afraid of their power, Crom agreed to convert to their faith. Before doing so, the monks punished him by burying him for three days with only his head above the ground.

The Ronadh Crom Dubh, or ‘the staff of Black Crom’ is a standing stone associated with a stone circle at Lough Gur in Co. Limerick, where offerings of flowers and grain are left at harvest time.

Crom Cruach/Dubh has a festival day on the last Sunday of July called Domhnach Chrom Dubh, where vigils and patterns are held at holy wells around the country in his memory. An association with St. Brigid is recognized in an all-night vigil still held on Crom’s feast day at her holy well in Liscannor near the Cliffs of Moher.

This seems surprising when one thinks of the terrible deeds once committed in his name, but as someone who repented and converted, becoming a supporter and friend of the Christian saints, it probably demonstrates the power of forgiveness we are all taught to aspire to.

As I stood blinking in the bright sunshine in the center of the plain of Magh Slecht, having relived its legacy at each prehistoric structure, with the green fields vibrant against the blue sky, Sliabh an Iarainn and Cuilcagh a hazy purple smudge on the horizon, I was struck by the great sense of peace and serenity which lay over the land.

These monuments practically stand in people’s back gardens, yet from the road which meanders by, they cannot be seen. They are, in effect, hidden in plain view. It seemed to me that nature, the age-old Gods, the Sidhe had all conspired to keep them safe.

Our ancestors certainly knew how to pick a site. It was hard to equate this place with such a perpetual dark scene of violence. I couldn’t help but wonder if such crimes had ever taken place at all, or whether we were unwilling victims of some early Christian propaganda. Perhaps it wasn’t children who were sacrificed here, but truth.

----

NB. I would like to thank Mr. Oliver Brady for taking the time to show me around the magnificent Magh Slecht. If you would like to know more about this site, archaeologist Kevin White has undertaken a very comprehensive study of the area.

Ali Isaac lives in beautiful rural Co Cavan in Ireland, and is the author of two books based on Irish mythology, “Conor Kelly and The Four Treasures of Eirean,” and “Conor Kelly and The Fenian King.” Ali regularly posts on topics of Irish interest on her blog, www.aliisaacstoryteller.com

* Originally published in 2014. Updated in March 2024.

Love Irish history? Share your favorite stories with other history buffs in the IrishCentral History Facebook group.

Comments