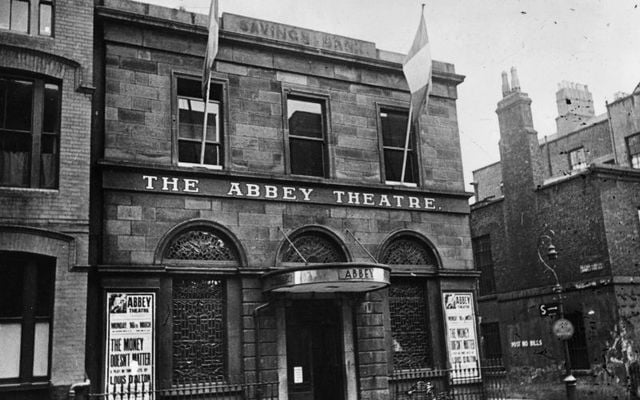

On January 26, 1907, John Millington Synge's “The Playboy of the Western World” opened at the Abbey Theater in Dublin.

The production caused such a fuss that projectiles were flung at the stage in what is now known as the "Playboy Riots."

The play tells the story of Christy Mahon, a young man running away from his farm, claiming he killed his father. Patricide was a shocking enough topic but the play also mentioned ladies' undergarments.

The riots were stirred up by the Irish nationalists who viewed the content of the performance to be an offense to public morals and an insult against Ireland.

"A vile and inhuman story"

Sinn Féin leader Arthur Griffith described the play as "a vile and inhuman story told in the foulest language we have ever listened to from a public platform." He also perceived it as a slight on Irish womanhood.

Sadly, within two years Synge was dead but his play was well on its way to becoming a global success. However, by 1911, when the show went up in New York, it seemed that little had changed.

Potatoes, stink bombs, and rosaries are just three of the items hurled at the stage of the Maxine Elliott Theater on November 27, 1911, as a riot again engulfed the auditorium and police expelled protestors.

Roosevelt and Lady Gregory

Standing in front of the audience, a rotund and determined Lady Augusta Gregory urged the actors to “Keep playing.” The founder of the Abbey Theater and patron of W.B. Yeats clinched victory two nights later when she arranged for Theodore Roosevelt, the former US president just two years out of office, to attend the performance.

Roosevelt and Lady Gregory were friends. As part of the rich tapestry of her ascendancy background, Lady Gregory’s great-grandfather had known George Washington. The audience applauded Roosevelt and his enjoyment of the play won them over. Lady Gregory’s canny diplomacy had disarmed the rioters.

The frenzy caused by The Playboy in New York was a repeat of the violence that greeted the play when it premiered in Dublin in 1907. Audience hostility, aroused by the depiction of Ireland, ignited over the use of the word “shift” (underwear) in the second act.

Lady Augusta Gregory (Public Domain)

Lady Gregory and the US

Despite removing the contentious lines from the text before the US tour, "The Playboy" provoked an uproar. After further rioting in Philadelphia in January 1912, the local Clan na Gael leader brought an injunction against the production on the grounds of indecency and the actors were arrested. John Quinn, a New York lawyer and Irish American patron, won the court case and the tour continued to Pittsburgh, Indianapolis, and Chicago.

As Judith Hill reveals in her biography, "Lady Gregory: An Irish Life," these events in the US had a transforming influence on the life of the woman at the heart of the Irish Literary Revival. From the moment the 59-year-old docked in Boston on September 29, 1911, she was on a new path.

“When Lady Gregory went to the US, she was seen as independent, warm and as a very attractive figure,” says Hill. “She wasn’t fazed by the opposition. She knew that the potential stirrers of opposition were a small minority.

“There was a strong desire among mayors and police to allow the play. She appealed to them. She was instinctive and uninhibited. When she was in Ireland, she was more closeted.”

Despite her reputation as a pioneering folklorist and her prolific literary output (including 42 plays, biography, stories, and poems), Lady Gregory had a very traditional view of the role of women and had never spoken in public.

But as she was embraced by the US press for her vitality, Lady Gregory was persuaded to speak to an invited audience in Boston. Soon, she was giving lectures, interviews and became the main defender against the United Irish American Societies’ resolution to “drive the vile thing [The Playboy] from the stage.”

Between 1911 and 1915, Lady Gregory traveled to the US four times. While touring with the Abbey Theater in December 1912, she raised $20,750 in funds to establish an art gallery in Dublin for her nephew and art collector, Hugh Lane.

Sadly, bitter disputes with Dublin Corporation meant that it was almost 50 years before the gallery would eventually open. Lane would never see it as he was on board the British-registered Lusitania when it was sunk by the Germans off the coast of Cork in May 1915. Lady Gregory’s son, Robert, was also killed in the First World War and is commemorated in Yeats’s renowned poem "An Irishman Foresees his Death."

Lady Gregory’s first visit to the US didn’t just change her public persona. She also fell in love with John Quinn, the lawyer who defended the Abbey players in their Philadelphia court case. Lady Gregory is seen as a classic Victorian figure, aloof and repressed. But as Hill’s insightful biography shows, Lady Gregory – described as “Ireland’s greatest living Irishwoman” by George Bernard Shaw – was a passionate and complex character.

“Why do I love you so much?” she wrote to Quinn, 18 years her junior, shortly after her return to Ireland in 1912. “It ought to be from all that piled up the goodness of the years. Yet it is not that – it is some call that came in a moment – something impetuous & masterful about you that satisfies me – that gives me perfect rest.”

By the time "The Playboy" tour limped to Chicago, the last stop on the American tour, in February 1912, it was derided as "Cowboy of the Western World." In the Windy City, Lady Gregory received a death threat in the form of a sheet with a rough drawing of a coffin, hammer, nails, and a pistol. On it was scrawled: “your fate is sealed never again shall you gase [sic] on the barren hilltops of Connemara.”

Lady Gregory was unperturbed. She continued to walk to the theater every night and caustically dismissed the threat when she remarked to her friend: “I don’t feel anxious, for I don’t think from the drawing that the sender has much practical knowledge of firearms.” Ouch.

"Lady Gregory – An Irish Life" by Judith Hill is published by The Collins Press.

* Originally published in 2011. Updated in January 2025.

Comments