Irish soldiers faced stigma and shame when returning home from fighting in the Second World War.

The book, "Returning Home" (2012), is by the Galway historian Bernard Kelly, and investigates the shameful way the estimated 12,000 Irish veterans who returned to Ireland after the end of the Second World War were treated.

Let's put it like this -- it's a long way from "Saving Private Ryan".

You would think that after fighting Hitler's armies the returning ex-servicemen would have got a hero's welcome home. But they didn't.

Instead, they came back to a country that was scornful of, ignorant of, and indifferent about what they had been through. In many cases, they faced open hostility. Their service in the British forces was seen by many at home as anti-national, almost traitorous.

The book tells the stories of many of these Irish servicemen and women who fought in the war, but I particularly liked the one about a guy called John Kelly who left rural Kilkenny to join the British Army and ended up fighting the Germans in North Africa.

In 1943, after the heat of the battle to liberate Tunis, the capital of Tunisia, he was sitting in a bar in the city center having a drink; also there celebrating the liberation of the city were some American conscript soldiers.

Hearing his Irish accent, the Americans said, “Say, you guys are neutral, you’re not in the war at all!” Kelly explained that he was a volunteer. The reaction of the Americans was, “Are you goddamn mad or something?”

It was a fair question. Kelly, and thousands of other Irishmen like him, had left the safety of neutral Ireland and risked death or injury to fight in the Second World War. They played their part in defeating Hitler.

But they got no thanks for it when they came home. It's a disgraceful and shameful part of recent Irish history. It shows how small-minded and inward-looking Ireland was at the time.

Love Irish history? Share your favorite stories with other history buffs in the IrishCentral History Facebook group.

De Valera had kept Ireland neutral during the war while the British and the Americans fought the most brutal and evil regime the world had ever seen.

Whether that decision was morally justifiable given the murder and mayhem unleashed across Europe by Hitler is arguable. One can take the view that as a weak, newly independent country we had other priorities.

But at the very least the sacrifice made by thousands of Irish people who volunteered to fight Hitler should have been recognized when they came back. After fighting the Nazis the 12,000 Irish veterans deserved that much.

Instead, they came back to a country where their attitude to them was so poisonous they quickly learned to keep their war service secret.

Even worse, of the 12,000 Irish veterans an estimated 5,000 had deserted from the Irish Army to join the British and fight Hitler and they faced potentially severe punishment when they returned home. All of the veterans also had a practical reason for keeping their mouths shut -- they came back to a country that was severely depressed, and being an ex-serviceman did not help in the search for a job.

There was a lot of ignorance in Ireland about the war. Unlike in Britain, where the entire country had been caught up in the war effort and as a result had great admiration for the returning soldiers, the Irish public had little understanding of the veteran's experiences.

All the Irish public had been through were the minor inconveniences of what de Valera called "the Emergency," which involved keeping the country on alert and putting up with some shortages and rationing.

Even the terminology says a lot about Ireland at the time. The rest of the world had a world war. In Ireland, we had "the Emergency."

Despite the ignorance here, however, by 1945/’46 many Irish people were aware that details of Nazi atrocities were emerging. You would think that this might have changed attitudes. But it didn't.

"Word of Nazi atrocities were filtering back to Ireland, partly through the media and partly through people like Dubliner Albert Sutton, who visited Belsen soon after it was liberated and saw harrowing scenes there," Kelly said at the launch of his book.

"But the whole experience of neutrality had opened an emotional breach between the Irish population and the U.K. Censorship, isolation and neutrality meant that while many people in Ireland were well aware of the war, they had no attachment to it. There was a genuine sense of pride and satisfaction that Ireland had avoided the war, despite pressure from London and Washington.

"When ex-servicemen returned their friends and family were delighted to see them, but they encountered indifference from the government and much of the population. There were no bands out to meet them because most people did not see the Second World War as Ireland's war; it wasn't something to be celebrated.

"From the government's point of view, they had not fought for Ireland, so they were not Dublin's responsibility. As for the bulk of the public, they simply didn't understand what the veterans had been through," Kelly said.

One writer quoted by Kelly recalls that in his home city of Cork they "were more concerned with the horrors of rationing than with anything that was happening in Europe.” This sums up Irish attitudes at the time.

The whole business is still a very sensitive subject, even today. When Kelly was doing interviews for the book many of the surviving veterans and the families of deceased veterans asked him not to use their surnames or addresses. For that reason, the servicemen and women are referred to in the book on a first-name-only basis.

Love Irish history? Share your favorite stories with other history buffs in the IrishCentral History Facebook group.

A man called George returned to Dublin from service with the Royal Navy, and he said it felt "as if you didn’t exist -- nobody wanted us."

Another man called William, who left Dublin to join the RAF, was dumbfounded by the ignorance of the war in Ireland. He was told by his neighbors that stories about German concentration camps were simply "British propaganda."

Another man called Larry, who left Wicklow to join the Royal Navy, was absolutely "shattered" by people’s attitudes when he returned home. He says that his fellow countrymen were interested only in "drinking themselves into oblivion, not a single thought about what was going on beyond the horizon. And they didn’t care a damn either."

One can understand the anger of many Irish ex-servicemen who had been through a lot during the war, in ways that changed their lives forever. Back home, however, people did not want to know or just didn't care.

John Kelly, the guy in the bar in Tunis, is an example. He was aboard the Polish ship Chobry when it was sunk off the Norwegian coast in April 1940, and barely escaped with his life. He fought his way through North Africa and stormed ashore at Anzio in Italy in 1944, where he was severely wounded and almost died.

He says he was rescued by a Kerryman, but then was further wounded by an RAF airstrike. He was evacuated and was invalided out of the army afterward.

His brother fought in the Far East. John died in 2009 and there are pictures of him in the book.

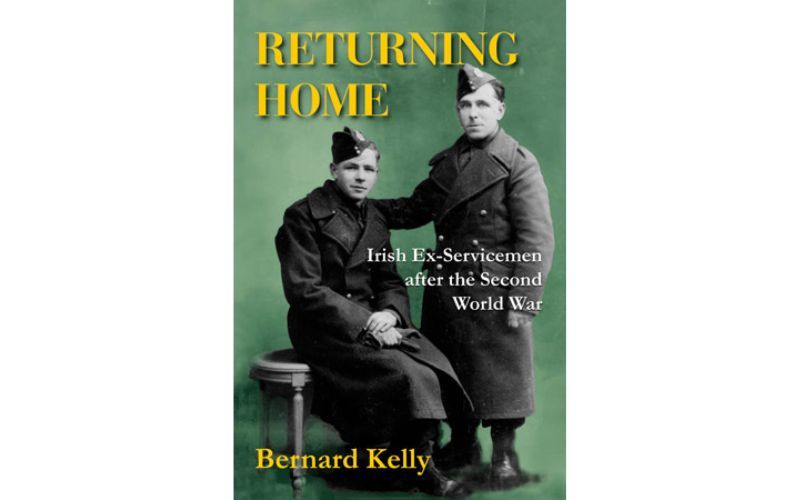

But my favorite picture is the one on the cover of the book, which you see here.

"Returning Home" (2012), by Bernard Kelly.

The two young men are Michael and Paddy Devlin, both from Longford Town.

Like many Irish from the south, they crossed the border to join the British army in Enniskillen in 1939 at the start of the war. They were posted to different units and fought in France.

Their units were smashed by the German attack in May 1940. Both were evacuated from French beaches. The men survived the ordeal but are now deceased.

Based on interviews with surviving veterans and drawing on a wide array of archival sources, Returning Home explores how the Irish ex-servicemen coped with the frosty welcome they got when they came back to Ireland, with the difficult task of re-integration, their economic difficulties and psychological problems.

Looking for Irish book recommendations or to meet with others who share your love for Irish literature? Join IrishCentral’s Book Club on Facebook and enjoy our book-loving community.

The treatment of deserters from the Irish Army who joined the British to fight in the war is only now being addressed, nearly 67 years after they came home. The minister for defense here made a statement in February indicating that official steps are being taken to issue a formal pardon to all such veterans, alive or dead.

It's been a long time coming. It's disgraceful that it has taken so long.

But of course, the delay did not stop people here from getting all misty-eyed over movies like "The Longest Day" or "Saving Private Ryan" over the years.

Overall, Returning Home makes an important contribution to how we view Ireland's connection to the Second World War and Irish participation in it.

The book is published by Merrion, the new history imprint of the Irish Academic Press. Kelly is currently working as a post-doctoral research fellow at the University of Edinburgh.

Comments