Can you imagine receiving a stiff fine for wishing someone Merry Christmas?

It sounds like something from a dystopian future imagined by those who annually complain about the "war on Christmas."

This scenario is actually from 17th-century Boston, where Christmas was banned for over two decades in the 1600s. That's right – from 1659 until 1681, it was officially illegal to observe Christmas in Boston by taking the day off from work, feasting, or celebrating in any other way.

Those in violation were fined five shillings – the exact contemporary value of which is debated by economic historians – but suffice it to say, was an incredibly steep fine back then!

So what gives, 16th-century Bostonians? Have historians since discovered that the hearts of these colonial grinches were two sizes too small?

Or is there a more nuanced, fascinating historical explanation? Of course, there is!

"Christmas is so 200 B.C."

Understanding the social and political climate in England and her colonies in the 1600s is key to figuring out why the heck Christmas got banned in the first place. At that time in history, the majority of the population of Boston was Puritan. The Puritans spurned the traditions of the Roman Catholic Church and constantly rallied against the Church of England for adopting any remotely Catholic practices.

The extremely conservative tenets of Puritanism yielded more than a few reasons for Bostonians to despise Christmas:

It wasn't really the birthday of Jesus - December 25 was only declared the birth of Jesus by Pope Julius I in the 4th century A.D. Since then, many have debated the date of the actual birth of Jesus, with very little consensus. But either way, the Puritans were all about scripture. According to them, there was nowhere in the scripture that said to celebrate December 25 as the birth of Jesus, so they saw no need to.

Christmas was too pagan: Not only was the observation of Christmas left out of biblical texts, but the date of December 25 was also a decidedly blasphemous one: Julius I likely picked December 25 to hasten the adoption of the Christian holiday. It now coincided with an already widely-celebrated Roman holiday, Saturnalia – a celebration filled with raucous parties and drunken misbehavior. Puritans were always quick (and usually correct) to highlight the Pagan underpinnings of Catholicism.

Love Irish history? Share your favorite stories with other history buffs in the IrishCentral History Facebook group.

Partying was un-Puritan: Puritans had particular problems with wild behavior induced by alcohol and gluttony. Conservatives in England and the Colonies campaigned against the Christmas tradition of "wassailing," in which the lower classes would go door-to-door requesting food and drink from their wealthier counterparts in exchange for toasting their good health. If refused, the hosts would suffer a great deal of mischief or even violence. Interestingly, this debate gave rise to Father Christmas in England. Proponents of Christmas merriment often invoked this personification, who was a mild-mannered cheery old man who had a "good but not too good" time on the holidays.

Rebellion against England: Yes, the Colonists were already clashing with the English government over 100 years before the American Revolution. New Englanders believed the Crown meddled in their affairs all too often, and Christmas was yet another example. Colonists saw the celebration of Christmas as an extension of English interference in colonial affairs and an affront to their freedom and independence. In fact, Bostonians eventually revolted and attempted to overthrow an English governor who forced shops and schools to close on Christmas in 1686.

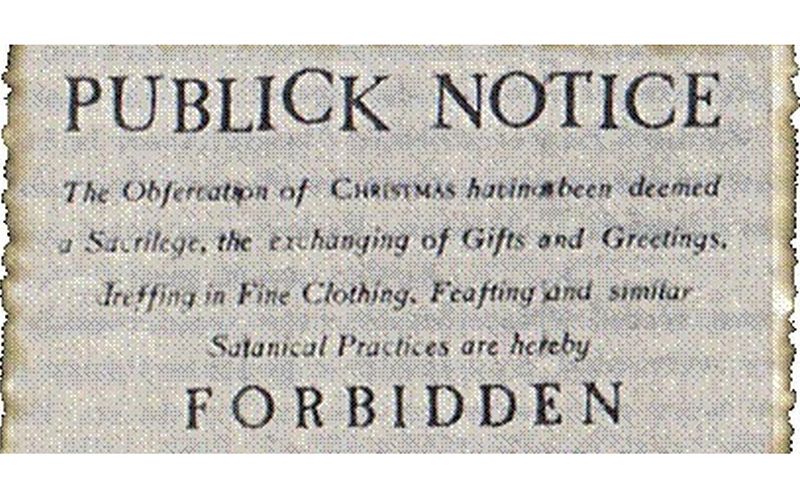

Public notice banning Christmas in Boston.

Christmas restored, sort of

You would think that such a ban would be met with outcries from the general population, but that wasn't the case initially. Most Bostonians wholeheartedly agreed with the ban, and in fact, relished working on Christmas Day as an act of defiance against meddling foreign governments and rival Christian sects.

As the English government struggled to control Puritan New England, the Crown installed English-friendly governors who re-instituted laws supporting English customs. The ban on Christmas was finally lifted in 1681, but the Puritans continued to rally against the holiday – many sources recount Puritans marching through the streets on Christmas Even shouting "No Christmas! No Christmas!" well after the ban was lifted.

This social ban on Christmas didn't really wane even as non-Puritans immigrated to Boston. Schools were officially open on Christmas Day as late as 1870, with harsh punishments for children who skipped out.

Elsewhere, outside of the Puritan-dominated Northeast, Christmas was more widely celebrated. Colonists in Jamestown noted a successful celebration early in their arrival in Virginia, and other states in the U.S. recognized Christmas as an official holiday in the early 1800s.

In 1870, Ulysses S. Grant was the first president to declare Christmas a national holiday, and, thanks to Charles Dickens' A Christmas Carol, the holiday experienced a renaissance, the fruits of which we enjoy to this day.

* Originally published in 2015, updated in Dec 2023.

Comments