In 1863, the Tennessee settlement now known as Erin was just a few stores and a camp of Irish railroad workers.

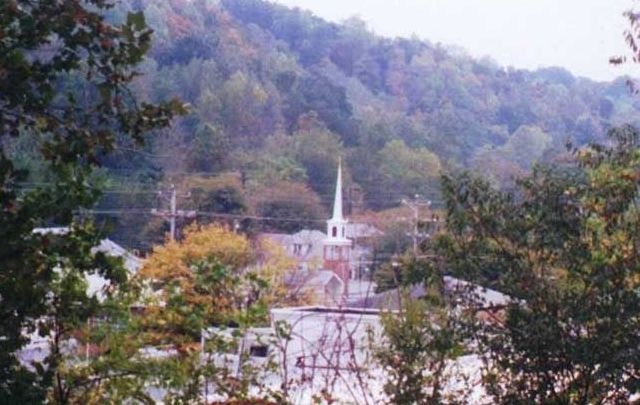

In Erin, legend has it that the Irish living there declared that “the hills and creeks reminded the Irish of their native Ireland and named their town Erin.”

According to Houston County’s Chamber of Commerce, this is correct and “the clear creek, wooded hills and fog hovering over the West Fork of Wells Creek reminded them of the 'Auld Sod' of Ireland.” Today the town is also known as “Irish Town Tennessee.”

The railroad that the Irish were building connected Louisville, Kentucky, and Memphis, Tennessee through Houston County. The line was finished two days before the beginning of the Civil War and the town of Erin was featured on the official Federal Forces map. During reconstruction (following the war) the railroad built a depot, hotel, and roundhouse in Erin.

For the most part, the earliest Irish immigrants to settle in Tennessee were Scots-Irish. In the 1760s and '70s, they were instrumental in founding towns such as Knoxville and Nashville. In fact, all three of the United States presidents from Tennessee who claim Irish ancestry were Scots-Irish. Another notable figure who settled in the area was Davy Crockett.

By the 1820s, Catholic parishes were popping up in Tennessee, and during the 1840s there was an influx of Irish fleeing the Great Hunger. The “new” Irish were seen as the poor laboring class.

Tennessee experienced a massive increase in the number of Irish people at the time. The Volunteer State had the seventh-highest percentage of Irish people of all the states. The Irish populations in Knoxville, Nashville, and Memphis increased four-fold, and “Irish towns” such as McEwen and Erin were established.

This period brought success for some Irish folk in the area. One example was Michael Burns from Sligo who became the director of two railroads and banks and served in the state legislature.

He was an exception though. Most Irish lived in poverty in overcrowded slums.

Hostility towards the Irish rose aided by the Know Nothing movement, which wanted to purify American politics and drive out Irish Catholics and immigrants.

The onset of the Civil War was an important milestone for the Irish in Tennessee. The Irish recognized that they would have to show solidarity with their newfound home. They formed various units to fight for the Confederacy such as the Second Tennessee Volunteer Infantry, which was nicknamed the “Irish Regiment,” the 10th Tennessee Volunteer Regiment, known as “The Sons of Erin,” and the Third Cavalry, led by Nathan Bedford, which was made up entirely of Irishmen.

By 1868 a branch of the Ancient Order of the Hibernians had been established in Nashville along with the Hibernian Benevolent Society and later the Parnell Branch of the Irish National League was founded.

The Irish influence in the town of Erin is still visible today and the Irish heritage of the town's founders is celebrated.

By the early 1980s, the railroad was abandoned and Erin established the Betsy Ligon Park and Walking Trail on the abandoned railroad tracks and built the Railroad Memorial Pavilion. A four-panel tribute to the railroad workers is hung on the pavilion wall. A Box Car and Caboose is located in the park for display.

Where the railroad once was is now a two-mile walking trail, which winds its way through the town’s historical district, passing by Victorian homes and businesses that are over 100 years old. There are also three lime kilns, 50 feet in height, dating back to the same era when the quarry was in operation.

The Irish are never forgotten in the town of Erin, which has marked St. Patrick's Day with special events for more than a century.

* Originally published in 2015. Updated in November 2023.

Comments