A look at Dan Hummel's journey from the US to Ireland and his life in West cork.

“I’ve always been into locations. Places have guided my life more than people, family, or friends,” Dan Hummel’s American accent, still strong, is as laid-back as the man.

“Maybe that’s why I find myself in west Cork, mostly alone for forty-six years, on this beautiful stretch of rock jutting into the Atlantic.

“I left America just as Nixon was coming in. I could see it was going nowhere good. And I was right. I could have had a decent life there, but it’s just not a nice place to be.”

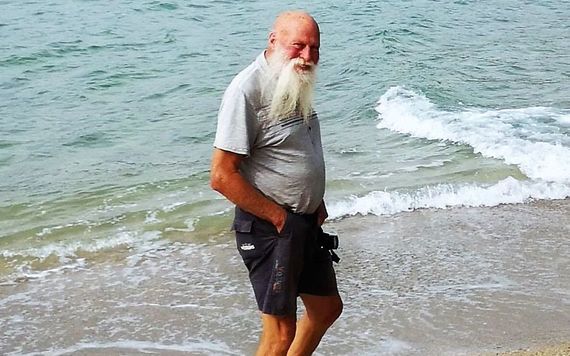

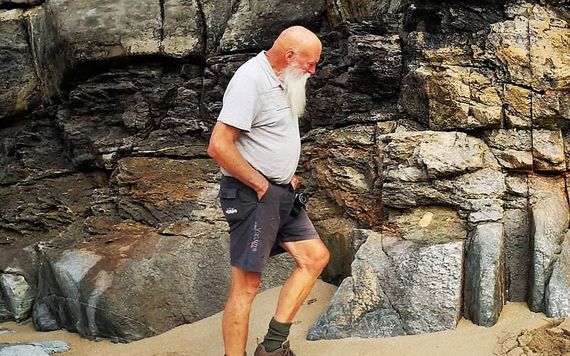

The rare Irish sun scalds his bald, red head, and his foot-long beard rages white in the wind.

Fifty years ago, after his first tour of duty, Dan backpacked across Vietnam. Half a million American troops were already on the ground, and Operation Rolling Thunder, the US aerial bombing campaign, was in full swing. Here Dan saw the future: Americans increasingly encouraged to value themselves by what they did and bought. And that America’s constant foreign wars were vital to uphold this value system. Soon after, he opted out of America for good.

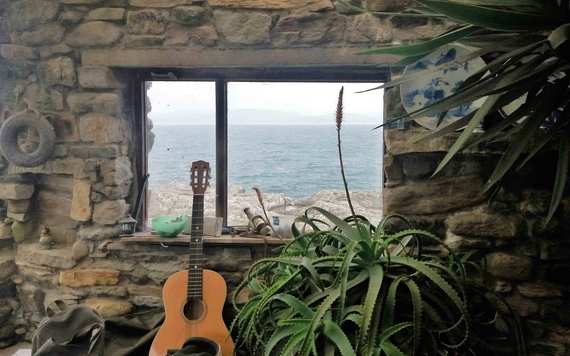

The front on the house Dan Hummel built with his own hands. Image: Brian Keane.

“Can’t think why I ended up in Ireland:” Dan draws Ireland out half the day.

“My family comes from German immigrants in Pennsylvania, and I’d lived in many beautiful places: Japan; Taiwan; Bainbridge Island off Seattle; Florida; San Francisco. The only connection with Ireland was I came here playing rugby with Dartmouth University in 1962.

“We played Trinity and UCD.”

Dan smiles exposing a ruin of teeth – chipped or broken, or just long gone.

“I guess a little bit of Ireland stayed in my mind because I came back ten years later, cycled to Bantry, then kept heading west until I found my place. Had a little cash, so I just bought it there and then.”

Once the raw beauty of the place brought Dan the greatest peace. Now, at 78 years old, it can leave him anxious: “One time I was hacking bamboo with a scythe and buried the blade about four inches into my leg. I missed the artery but the blood was spraying everywhere. It was a long crawl to my home where I tied a shirt around it. I had to hobble the 700m to my bike, and then cycle 17 miles to the hospital. Don’t think I have that in me anymore. These days my balance isn’t so good, and the paths are slippery. But I guess there are worse ways to go. At least I’d die here, where I’ve spent more time than anywhere else in the world.

How I first met with Dan

Dan Hummel and Brian Keane reunited in West Cork after twelve years since meeting in West China. Image: Brian Keane.

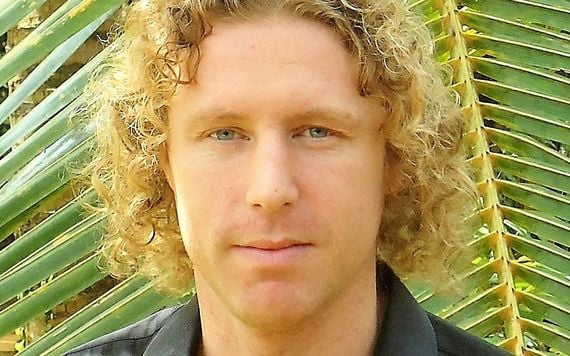

The first time I met Dan was in Yunnan Province, west China, way up on the Tibetan Plateau. He’d built a rustic retreat clung to a mountainside 3000 meters above sea level. Overlooking the ancient kingdom of Dali, he’d named it the Higherland Inn – a play on words that in Mandarin reads Ai 爱 – Er 尔– Lan 兰 , the Chinese characters for Ireland.

Delighted to meet a Corkman in that lost part of the globe, we eased our nostalgia toasting Johnnie Jameson, Dan showing me photos of his rugged sanctuary on Sheep’s Head, and me swearing blind that one day I’d visit.

On that Chinese mountain, he was known as Higherland Dan. Later, when I opened my own place in Dali, he arrived with a tipi strapped to a couple of donkeys. To a bemused audience of local farmers, and a motley crew of western backpackers, Dan single-handedly erected the massive white and sky-blue wigwam—possibly the first-ever in China—in my garden without breaking even a hint of sweat.

Are you planning a vacation in Ireland? Looking for advice or want to share some great memories? Join our Irish travel Facebook group.

People passing through would recognize the grand tipi as belonging to the American with the white beard, but they knew him as Tipi Dan.

Teaching in Japan in the mid-sixties he was Dan Sensei. And before that, in the US Navy, he was Lieutenant Dan. These days, friends in Ireland call him China Dan, while to most Chinese he’s Ai – Er – Lan Dan.

But in west Cork, cycling to Bantry town in every weather for almost half a century has earned him the name: The Man on the Bike.

Making the journey to Dan's solitude in Cork

Finally making good on my promise, we head west. Out of Bantry through the tiny villages of Rooska and Glanlough until we run out of road at Glan Roon. And still, we move west following a grassy track down to the sea.

At an old wooden box—Dan’s telephone booth before the days of mobiles—the old man slips inside a wall of brambles to locate a rickety wooden gate. On the far side, we emerge onto a wind-shafted expanse of rock and tough grass. On our right, the ocean growls. This is the kind of terrain that firmly establishes you in the west of Ireland.

Half-crippled beneath the awkward weight of Bord na Mona peat briquettes, our bags, and food supplies, we pick our way along a scattering of stones worn smooth by only one man’s feet. It dawns on me he must have laid the path with his own hands; finding, carrying and placing one large, flat stone after another. Each slab might have been a day’s work, and we trace them for a winding 700m until a battalion of tall cairns rises from the headland.

The zen stones are stacked higher than my head, and from their midst, Dan’s house seems to grow straight out of the ground. A squat block of uneven stones spouting from a violent slice of naked rock, the dwelling’s roof a mullet of grass so enmeshed with its craggy environment you’d pass it if you weren’t looking.

One of the many tall cairns Dan Hummel erected in front of his house. Image: Brian Keane.

Established on the cusp of a hillock, the two-roomed outpost surveys a demented finger of rock currently being abused by the Atlantic. The big whoosh and crash of the waves juxtaposed against the endless wilderness on the other side, affects the most ancient part of me, and the only thought capable of survival in my head is: “Why would anyone choose to live here?”

Inside, there’s only small evidence we are not in the 19th or earlier centuries. Rather than voice my distress, I suggest tea. Dan drops his slab of peat on the bare rock that is his floor, picks up an enamel bucket, and offers to get water.

All 78 years of him shambles off along a grassy ridge, and though a broad pillar of a man, when he walks, it’s like his backside has caved in, giving him the bow-legged gait of a caricature from a western. I watch him cross a meadow of tall grass, his whole apparatus moving like a bag of potatoes, until all that remains is a smudge against the colossal landscape dipping a bucket in a stream, and I wish I’d never mentioned tea.

Dan’s cave-like space is littered with random bits of Chinese and Japanese ornaments, and further cluttered by pillars of books rivaling the standing stones outside.

“Time’s Up” by Keith Farnish is the first to find my hand. A book about survival in a civilization that’s killing our species in exchange for superfluous goods and cheap thrills. Beneath that is “When a Billion Chinese Jump – Voices from the frontline of Climate Change.” Then, “Bad Samaritans – The Guilty Secrets of Rich Nations and the Threat to Global Prosperity.” And stacks more political non-fiction, the majority examining American domestic and foreign policy.

This article was originally published in Ireland of the Welcomes magazine. Subscribe now!

Beside a guitar, I spot “The Tibetan Book of the Dead,” reminding me of something Dan said on the drive down: “Been having some real nice dreams recently, maybe the subconscious preparing the way for death.” Then he winked like he had said it just to gauge my reaction.

On his eventual return, I put the water on the small stove—only exactly what’s needed—as the big bottle of Calor gas surely arrived here via Dan’s back.

No water. No electricity. And to my bathroom inquiry, Dan points at the rocks extending directly out from his sitting-room window into the livid Atlantic: “You’ll see a crevice down there that’s perfect for the job. Everything taken away immediately.”

Inside Dan Hummel's house. Image: Brian Keane.

Squatting on the headland, June’s breeze carries sea spray to cool my bare arse. I enjoy the novelty, but a premonition of doing it in winter sullies the occasion. Knowing Dan has hunkered down here in all weather, in sickness, and in health, for forty-six years, brings me a new depth of respect for the man.

Back at the house, by the window, in the only chair—a seat recycled from the passenger side of a comfortable car—Dan oversees the Atlantic. The wind whistles through the gaps where Dan’s house doesn’t quite fit together and I brew us Chinese Pu’er tea until it’s blacker than Irish stout.

Beneath a frayed string of bright Tibetan prayer flags, there are washed-out maps of west China spread bumpily over his bare stone walls. I recognize the features of Dali Old Town—the region Dan tries to spend his winters—though I can’t read Mandarin very well. But Dan can. Fluent in spoken and written Japanese means he has a fair grasp of Chinese characters too.

How Dan found his way to West Cork

Dan Hummel on the beach on his land.

From an academic background, Dan graduated as a geography major from Dartmouth University—one of the Ivy League, and among America’s oldest third-level institutions. Fellow alumni include the poet Robert Frost, the children’s writer Dr. Seuss, one-time US vice president Nelson Rockefeller, and former Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson—one of Time Magazine’s “25 people to blame for the 2008 financial crisis.”

In 1963, military service was still compulsory, so Dan joined the navy with an eye to getting a posting in Japan—a country which had caught his interest. Based at an officer training school in San Francisco when Kennedy was shot, Dan was keen to leave by the time he sailed out a few months later on the USS Surfbird.

His quiet Japanese base afforded him many days on his motorbike exploring rural Japan and learning the language. Until the USS Surfbird was ordered to take part in Operation Market Time—the US Navy’s effort to stop the flow of troops and weapons by sea from North Vietnam to the South. An uneventful mission but made Dan a Vietnam veteran nonetheless.

Already probing the wisdom of the American system, even Dan’s superiors could see his uniform was an awkward fit. And as soon as his three year’s military service was complete he left the Navy and became an English teacher.

In Nagasaki, the children called him Dan Sensei, and here he befriended eye-witnesses of the second atomic bomb ever detonated on a human population.

“They said the bomb blast wasn’t the worst,” Dan tells me.

“The worst part was seeing the survivors walking around with their skin melted off. Every day I encountered horrific disfigurement that made me deeply question my country’s actions.”

From there Dan went on to teach in Taiwan which was under the martial law of defeated Chinese nationalist, General Chiang Kai Shek. Known stateside as General Cash-My-Check, the brutal dictator was supported by the United States as he was anti-communist. He permitted the US Navy’s 7th Fleet to patrol the Taiwan Strait—a key strategic position for keeping tabs on the Chinese Communist Party—and in return, the General received billions in economic and military aid.

The Korean War had ended 15 years earlier, and Dan noted the US military now had a strong presence in Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore, and the Philippines. Dan was becoming suspicious of America’s plans for global military and economic hegemony. Today, with the US military openly serving in more than 150 countries, Dan’s suspicions were proved correct.

In 1967, across the strait, as Chairman Mao’s Cultural Revolution was gaining momentum, Dan decided to leave Taiwan. As a private citizen, he backpacked through Vietnam while his countrymen dropped the largest payload in military history—including using Cluster Bombs, Napalm, and Agent Orange—in their attempt to “bomb them [the Vietnamese] back to the Stone Age.

From Vietnam to his first tipi

Inside Dan Hummel's house. Image: Brian Keane.

Witnessing the full horror of US foreign policy up close, and with the region set to explode, Dan decided it was a good time to return home when a Japanese business friend asked him to help buy property in the US.

He purchased a large piece of land on Bainbridge Island off Seattle.

“My father had bought ten acres in Pennsylvania and, as the eldest son, he put me to work on it,” Dan informs me.

“Then I saw the Japanese working the land by hand and thought I’d like to try that. Helping my Japanese friend I got the opportunity to work a piece of land myself, and to me, it just made sense as a way to live.”

It was here, just before the Summer of Love, that Dan acquired his tipi from hippies experimenting with alternative living. During these years, Dan also worked for the US State Department escorting dignitaries from undeveloped countries like Sri Lanka and Papua New Guinea around America’s sights. This opened his eyes to America’s domestic policy—individuality sold as a virtue expressed through the products and experiences one bought—and Dan decided to live a life that was truly his own making.

While still a ‘reserve unit’ in the US Navy, Dan was determined to avoid a second tour in Vietnam. So when Nixon came to power in 1969, Dan thought this would be a good time to travel the world, figuring out what to do with himself while visiting the dignitaries he had befriended: “That was a sweet gig because after I gave them the tour, complete with all the perks laid on by Uncle Sam, then I could visit their country as a private citizen, but be treated in the same style.”

Eventually landing back in the west, he took a Masters in Oriental Studies at the University of London. Then, ten years after his rugby tour with Dartmouth, he returned to Ireland.

Building a home out of nothing

The Japanese style hot-tub Dan Hummel built on his land that looks out across Bantry Bay to Bere Island. Image: Brian Keane.

At this point, Dan proposes firing up his hot tub. Reattaching himself to the metal harness that holds the peat briquettes, he half-hobbles, half-marches off again in the same direction as before. I follow, begging to take the load while Dan ignores my pleas.

All along the coastal path, we pass more heaps of stones, some as tall as Dan.

“I collect the rocks the ocean throws up before she reclaims them again,” Dan lobs the comment over his shoulder. “Someday I may build another house out along the coast…” he adds, seemingly unaware of the unlikelihood of this.

Three hours later we’re both naked, dunked in steaming water, and looking out towards the saw-toothed fold of rock defending Dan’s land from the Atlantic’s eternal grasp. The hazy grey bulge beyond, Dan assures me, is Bere Island. “In 1972 I started out with 12 acres. Now I have 120,” he tells me. “I kept buying because it was there.”

Our hot tub is a huge, stainless-steel milk container, which Dan has hooked up to a stove. Eyes closed and angled towards a struggling sun, I notice his redhead, that was smooth in China, is now coarse and scabby. From the sea-salt, I guess, like grit in a wind which never seems to fully rest, and the image of Dan using sunscreen or moisturizer can’t be conjured to my mind.

“First two years I lived on this very spot in a two-man tent. That flat rock over there was my dining table:” Dan points to a spot between two small freshwater lakes.

“I was interested in Japanese hot-tub culture so I set this up first and built a wooden bathhouse to shield it against the wind. Lived in that bathhouse another two years while I collected the stones to build the house I live in now. Good thing I had those stones too because one spring I came back from China to find the bathhouse smashed to pieces by a freak wave.

“I had no building experience and couldn’t figure out where to put my house. So, I just kept collecting rocks. One time I got a pile eight feet tall. Had to stand on a ladder to reach the top. I was proud of that.”

Dan smiles at the memory: “Any supplies I needed I cycled two hours into Bantry, strapped them to my back, then turned right around. I’d carry everything by hand the final half-mile to my place.”

There’s a pride to his voice when he talks about his capacity for hard labor.

“I just love being on this beautiful piece of land, especially on long summer days.”

Tibetan prayer flags hanging inside Dan Hummel's sitting room. Image: Brian Keane.

To the left the stream that provides Dan’s drinking water gurgles, and on the right, a grove of bamboo hugs a lotus pond filled with tall reeds.

“The pure physicality of it—just moving rocks all day, learning the flow of the terrain, alone, and with no particular goals beyond the basics…

“Guess I could have made more of the land, applied for forestry grants, and kept up with the sheep and goats. But I always wanted to spend as many winters as I could in warmer climes, in Asia, my second love ... And it’s hard to get things together when you’re always moving.

“Had that vegetable patch going once.”

Dan points at a green catastrophe hemmed in by a lumpy stone wall.

"When I was more organized that was full of beetroot; pak choi; sea beet; potatoes; Chinese cabbage, and I’d always try to grow enough marijuana for my own purposes.

“I kept sheep and goats too.”

He opens his blue eyes, pale as the freshwater lakes, maybe diluted from almost five decades peering at the Atlantic.

“But I haven’t the energy to organize this place anymore. Now it takes all I have just to live.”

The solitary living out of your days

Dan Hummel on the beach on his land. Image: Brian Keane.

When it gets too hot I walk naked from the hot tub to submerge myself in the closest icy lake—Japanese style. I do this half a dozen times but Dan doesn’t budge. His days have revolved around the tub since before I was born—soaking himself for several hours daily through summers and winters.

After dinner, with a childlike glee, Dan shows me photos of gatherings he used to throw to celebrate the summer solstice. Thirty or forty people scattered across the meadow. Children playing on the grass mown short by the sheep and goats. The hot tub full, and a band set up on the flat stone that spent years as Dan’s dinner table. In one picture, Dan is in the foreground, robust as a mountain, the beard just as white twenty years ago, and standing tall behind him is the tipi he donated to my guesthouse in China.

“Those were good times,” Dan says, a rounded stoop to his large shoulders that wasn’t there in Asia.

“But I don’t get many visitors anymore. Now it’s mostly just me, and this is no place for an old man.”

He tells me last month he was scheduled for a heart check-up at Bantry Hospital. At dawn, he hiked to the edge of his land, then walked a further three miles to the hitchhiking spot. He stood there for four hours but nobody picked him up. So, having missed his appointment, he hobbled home.

“With my health, I have four or five years left at best … They’re not going to be much fun. A life spent alone will most probably mean a death spent alone.”

All day, I’ve found myself looking for meaning in Dan’s story. What does Dan do? But that would be like inquiring what does a tree, or a stone, do? Dan has endured a thousand dark nights, the wind screaming through his soul and hard waves raining spray down on top of him. The life he chose has made his mind strong. Now, facing serious health issues and impending death, he seems relatively unfazed. But to face death with grace, is that it?

So, as the last light leaks from the day, I finally ask if his life had any purpose?

Dan tries to shrug the question off, but I insist.

“I just wanted to get people interested in working with a piece of land,” he says. “Out of necessity, most people’s life choices are driven by the need to make money. A few lucky breaks early on meant I always had just about enough. So that allowed me to shape my life differently. I never orientated this land around a commercial interest. I wanted to play with it. To enjoy it. To just be here. And offer an example of a different way to live.”

Note: For health reasons, Dan must leave his piece of Ireland to live closer to a hospital or move to Japan to die drinking sake. His 120 acres of west Cork coastline would ideally suit a rustic tourism venture or retreat, or a community of people wanting to live off the land. For inquiries please contact Brian Keane at [email protected]

Writer Brian Keane.

Comments