Domhnall O’Donoghue discovers the fascinating and intertwined history of Maynooth University and Saint Patrick’s College - Ireland’s national seminary.

Kildare, one of Leinster’s most elegant counties, has many jewels on its proverbial crown - the Japanese Gardens, Irish National Stud, Donadea Forest Park, and Castletown House - but few shine as brightly as the bustling town of Maynooth.

For those interested in etymology, the name Maynooth derives from the Irish ‘Maigh Nuad’ - the word ‘Maigh’ meaning planes while ‘Nuad’ or ‘Nuadhat’ was an ancient god.

Fittingly, the town, located some 25 kilometers west of Dublin City, will forever be linked to God and religion thanks to the presence of Ireland’s national seminary, Saint Patrick’s College - once the largest in the world.

Strolling around the calm and picturesque St Joseph’s Square, currently bestrewn in creeping ivy, it’s hard to think that the seminary’s genesis was so hard-fought. In fact, like a passage from the Bible, its creation in 1795 required its founders to overcome numerous obstacles in an Ireland where Catholicism was effectively outlawed.

Revolution in the air

Owing to harsh penal laws, for 200 years beforehand, Ireland’s Catholic priests had been forced to flock to colleges in France, Spain, Portugal, Italy and the Netherlands for their education and training.

However, the French Revolution in the latter years of the 18th Century shocked Europe to the core. Irish bishops feared that priests studying on the continent might be impressed by the ideals of the Revolution, so implored the British government - which was occupying Ireland at the time - to allow this education to take place in Ireland. At war with France, Britain was anxious to placate Irish Catholic dissatisfaction and agreed.

Tulips in the South Campus.

The ambitious project then extended beyond student priests to include Catholic laymen, and in 1795, Maynooth College was founded. Among its first staff were several French scholars who were refugees from the Revolution.

By the 1820s, Maynooth priests dominated the Irish clergy and proved to be the backbone of Daniel O’Connell’s campaign for Catholic Emancipation. By 1850, Saint Patrick’s had become the largest seminary in the world.

In 1871, following the Church of Ireland’s disestablishment in Ireland, St Patrick’s College achieved independence, and towards the end of that century, it had shape-shifted once again, becoming a Pontifical University.

School of thought

Another significant moment in its storied journey came in 1910, when St Patrick’s progressed into a recognized constituent college of the National University of Ireland, meaning clerical students pursuing seminary studies could also receive arts and science degrees. However, the Pontifical University continued to confer its own theology degrees.

The Swinging Sixties brought further, dramatic changes when students from all walks of life were welcomed, greatly expanding the college - by 1977, these lay students outnumbered the religious students.

Are you planning a vacation in Ireland? Looking for advice or want to share some great memories? Join our Irish travel Facebook group.

In terms of staff and students, St Patrick’s College enjoys a celebrated alumni. Father Nicholas Joseph Callan from County Louth was a Professor of Natural Philosophy here from 1834 but is best known for his work on the induction coil - a type of electrical transformer used to produce high-voltage pulses from a low-voltage direct current supply. Between the 1880s to 1920s, it was widely used in x-ray machines, spark-gap radio transmitters and arc lighting.

The National Science Museum, also located on the campus, houses fascinating artifacts from Callan’s research. In addition, there are non-scientific items on display, including vestments presented by Empress Elizabeth of Austria and the death mask of Daniel O’Connell, a man long associated with Catholic emancipation.

South Campus of Maynooth University at night.

Previous college staff include renowned playwright Frank McGuinness who taught English, and Éamon de Valera, former President of Ireland, who lectured in Mathematics and Mathematical Physics in 1912 - and took refuge here following the Rising four years later. Past students include Nobel Prize winner John Hume as well as one of Ireland’s most important contemporary dramatists, Brian Friel.

Seminary life

Over its long history, the seminary has ordained more than 11,000 priests, many of whom have ministered outside of the Emerald Isle. My dear friend, Dr Conor Farnan, a fellow Meathman, was a seminarian here between 2001 to 2003.

“I was inspired by the person and message of Jesus as I had experienced Him in the Gospels and in the priests who I had met,” Conor says of his motivations behind joining the seminary. He was one of twenty-two who joined in 2001; to his knowledge, about a dozen made it to ordination.

Conor - now a secondary school teacher in Crumlin, Dublin and author of Faith Alive, a religious book for students - explains that the average day at the seminary consisted of three sets of prayers and a morning mass along with communal meals.

He adds: “Outside of these shared gatherings, a seminarian’s weekday was quite like any other undergraduate’s - lectures, coffee with friends, time in the library, study and essay-writing.

“Where our lives were different was in the area of expectations: a seminarian is expected to live a chaste and fairly conservative life, so most evenings were spent chatting with classmates in the dorm-like corridors rather than pursuing love interests or drinking in the Students’ Union or The Roost.”

Conor eventually left the seminary for personal reasons but acknowledges how much he learned there.

Conor Farnan and his wife Anne-marie on their wedding day with Fathers John and Joe.

“Professionally, I’m now a teacher, which is its own kind of secular priesthood with dogmas, beliefs and rituals,” he explains. “So, in a way, I am still living echoes of the impulse that brought me to Maynooth.

“Personally, I think Maynooth taught me the value of kindness in day-to-day interactions. Large institutions can be brutalizing on the individual: it’s good to remember that every person – no matter how seemingly aloof – has feelings and deserves kindness.”

In 2016, two of his original classmates who went on to be ordained, Joe and John, married Conor and his wife, Anne-Marie. More recently, the two priests baptized the couple’s daughter, Aoife.

“Ours is a wonderful, life-giving and rich friendship that first took root all those years ago in Maynooth.”

When I discuss the institution’s future with Reverend Professor Michael Mullaney, President of St Patrick’s College, he tells me: “St Patrick’s College has navigated four very different centuries, adapting and adjusting to new developments and turbulent challenges in education, mirroring the changing socio-political and religious landscape in Ireland as well as the world around us.”

He believes the pandemic is another pivotal moment in their history, encouraging them to embrace new teaching and learning technologies and pedagogy.

“[The pandemic] has opened a window into the unique brand that is Maynooth, for a whole new constituency of remote learners around Ireland and the world. It has become an opportunity in which the college has refocused on its core missions, and plotted an exciting route for the coming decades.”

A saintly chapel

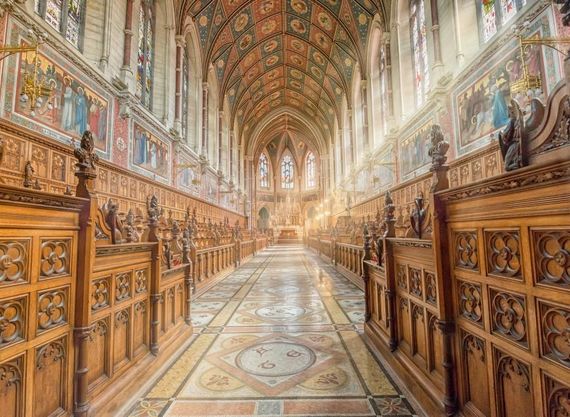

My own first memory of St Patrick’s College was as a young, not-always-in-tune chorister singing in their magnificent chapel. It was little wonder my 10-year-old self lost his way in the middle of Ave Maria, overwhelmed by the surrounding 454 carved stalls, which I now learn is the largest of its kind in the world.

Inside the Chapel at Maynooth.

The stunning 19th-century chapel was initiated by then-President Charles W. Russell, with architect J.J. McCarthy finding his inspiration in the 14th-century Gothic style popularised in France. The French also inspired the design of the breathtaking Rose Window - it was based on the Cathedral of Notre Dame in Reims, where their kings were once crowned.

Apart from floor mosaics, life-size Stations of the Cross, and a ceiling adorned with canvas medallions depicting saints and angels, another highlight here is the magnificent organ that looms over the entrance. The sweet-sounding instrument boasts a total number of 2,983 pipes, some of which politely lie horizontally, not wanting to interrupt our view of the Rose Window.

A Christmas Carol service is held here annually, open to staff, students and the general public. Such is its popularity; tickets are allocated by lottery.

The ghost room

With an institution that spans four centuries, there is bound to be some hair-raising ghosts skulking around the campus. In fact, any student here is quick to mention that Room Two of Rhetoric House has been associated with paranormal activity since the mid-19th Century. There, two young seminarians died by suicide, nineteen years apart.

If legend is to be believed, they were driven to their deaths by a ‘diabolic presence‘ in the room. A third priest spent the night in the room and was terrified by whatever he saw; in fact, his hair turned bright white.

In 1860, the room was converted into an oratory, dedicated to St Joseph, the patron saint of peaceful deaths. Today, the space is a waiting area among academic offices, but the seminarians’ remains are buried in marked graves in unconsecrated grounds outside the college cemetery.

A new dawn

In 1997, St Patrick’s College and the newly established Maynooth University were restructured, resulting in two separate, independent institutions. Even though their stories are closely aligned, and they continue to share one of the two campuses, Maynooth University has flourished on its own over the past quarter of a century.

With over 70,000 alumni across the globe and more than a thousand staff members, the university impressively made the Top 50 in the recent Times Higher Education ‘Young Universities’ list while also reaching the Top 500 in the coveted World University Rankings.

In addition to a strong focus on the humanities, social sciences and natural sciences, they are equally committed to research, teaching and engagement. I ask Sally Ní Dhroighneáin - a full-time tutor and lecturer in the Irish language and sean nós singing - what makes the university so unique. She immediately cites Maynooth’s status as Ireland’s only university town - the others being located in cities.

Sally, who originally hails from Connemara, also praises “the South Campus where Saint Joseph’s Square and the chapel are located - particularly in autumn when the creeping ivy changes colour.”

As it happens, she tells me that there is plenty to excite nature enthusiasts. The celebrated 'Silken Thomas’ yew tree in front of Stoyte House is approximately 800 years old and thought to be Ireland’s oldest native tree. The stunning, atmospheric entrance to the graveyard comprises of a series of yews that converge to form a vault-like cover.

“In contrast with the South Campus, the North Campus has a more modern atmosphere with impressive new buildings like Eolas and Iontas, which have a focus on computer science and business,” Sally explains. “In a typical, non-pandemic year, the atmosphere on both campuses is busy and lively - there are students and staff everywhere.”

Even though it’s a hub of activity, Sally praises “the friendliness and diversity of students and staff members, whether it’s in the lecture room, shop, bookshop or café.” One such eatery is the historic Pugin Hall, often likened to Harry Potter’s Hogwarts.

One thing is for sure, St Patrick’s College and Maynooth University are always sure to cast a spell on students and visitors alike.

* This article was originally published in Ireland of the Welcomes magazine. Originally published in May 2022. Updated in May 2024.

Comments