When it premiered in the US in 1952, Irish diplomats feared that The Quiet Man would provoke riots. Instead, the Maureen O’Hara and John Wayne film became beloved in Irish American circles.

On September 14, 1952, John Ford’s classic film The Quiet Man premiered in the US, marking the start of a decades-long love affair between Irish American audiences - as well as fans of classic films - and the technicolor wonders of 1950s Ireland, Maureen O’Hara’s red hair, and the undeniable chemistry between her and leading man John Wayne.

The movie, which John Ford (birth name John Martin Feeney) had been wanting to make since 1933 when he was captivated by a Maurice Walsh short story by the same name, was a runaway success despite the skepticism of the Hollywood executives who’d thought it would be a waste of time and money to send Ford, his cast, and his crew to Ireland. It grossed $3.8 million in box office sales (a hefty sum by the standards of the day) and went on to win seven Academy Awards, including Best Director and Best Picture.

All this makes it even more surprising to think that in the lead up to the film’s US debut, some Irish government officials were reportedly terrified The Quiet Man would spark riots from audience members once it entered US movie houses.

While locals in Cong, Co. Mayo, near Ashford Castle, and Galway, where director John Ford picked a number of key locations, were thrilled with the Hollywood stars in their neck of the woods, when the film debuted many Irish were less than thrilled to see themselves portrayed as drinking, fighting schemers and dreamers. This led to concerns that the film would be taken at face value and that American audiences would believe it portrayed what life was really like in Ireland.

After attending a preview of the film in April 1952, Joseph D. Brennan, a counselor at the Irish Embassy in Washington, wrote to the Department of External Affairs official Conor Cruise O’Brien about his qualms.

Brennan noted: “The color is beautiful. The scenery is delightful. But – the theme is not likely to be well received here.”

He asked what reactions to the movie had been like in Ireland and requested a reply at the earliest possible date, which wasn’t until “The Quiet Man” premiered in Ireland in June of that year.

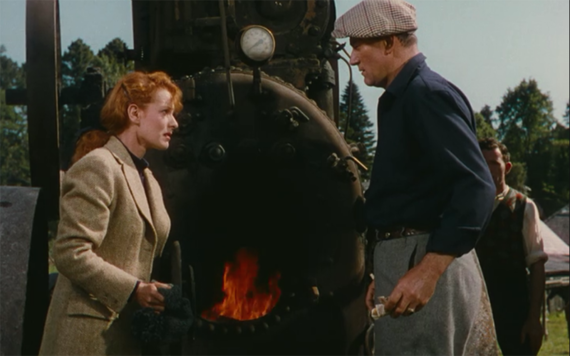

Still from "The Quiet Man."

Following up on his concerns in a July letter, Brennan expressed fear that there could be protests from Irish American viewers:

“If it were to be taken completely at its face value it would be accepted as a rollicking farce and no harm done but I fear it will be regarded by the Irish-American element here as purporting to portray actual life in Ireland. We may then have protests.”

As it turns out, he need not have worried. Audiences were delighted by The Quiet Man, as were most critics.

Still from "The Quiet Man."

The New York Times raved:

“It is obvious that in ‘The Quiet Man,’ [John Ford] actually went to the Emerald Isle with some of his veteran players, then enlisted some Abbey Theatre stalwarts before turning his Technicolor cameras on those fine bhoyos and colleens, a rollicking tale and the green, dewy countryside to come up with as darlin' a picture as we've seen this year.”

“This is a robust romantic drama of a native-born’s return to Ireland. Director John Ford took cast and cameras to Ireland to tell the story [by Maurice Walsh] against actual backgrounds,” Variety wrote.

“Despite the length of the footage, film holds together by virtue of a number of choice characters, the best of which is Barry Fitzgerald’s socko punching of an Irish type. Wayne works well under Ford’s direction, answering all demands of the vigorous, physical character.”

The Nation, however, had a much more withering take.

“Often during The Quiet Man the audience finds something laughable (the town drunkard and gossip muttering when he is offered buttermilk instead of whiskey, “The Borgias would do better”), but mostly the moviegoer has to put up with clumsily contrived fist fights, musical brogues spoken as though the actor were coping with an excess of tobacco juice in his mouth, mugging that plays up all the trusted hokums that are supposed to make the Irish so humorous-sympathetic, and a script that tends to resolve its problems by having the cast embrace, fraternity-brother fashion, and break out into full-throated ballads,” Manny Faber observed.

Maureen O'Hara "Quiet Man" still.

“In the midst of it is the formless love story of two champion poseurs, one of them a strong, silent ex-boxer from Pittsburgh, Massachusetts (gag), who, returns to the thatched cottage of his birth and spends the film wistfully lapping up luxurious scenery around Galway; the other, a hot-tempered, shy country wench who runs through streams clutching her broad-brimmed hat or compulsively glancing over her shoulder as she backs off to the very bottom of the screen. The characters are paper-thin types with traits taken from pulp stories, nineteenth-century novels, and a dozen British films starring members of the Abbey Theater.”

Ouch.

Opinions on The Quiet Man have grown exceptionally divided as the years have flown by, with some viewing it as the ultimate Irish film, full of sweet nostalgia and romantic Ireland, and others considering it laughably out-dated, if not problematic on a deeper level.

Writer Malachy McCourt declared that “'The Quiet Man' ranks among most idiotic stupid anti-Irish movies ever made.

“Wife beating, priest-ridden, blather talking gombeen men getting drunk standing around gossiping and then erupting into stereotypical Irish behavior violent fighting,” he listed in a viral Facebook post in 2015.

“John (Right Wing) Wayne could never qualify as an Irishman (too much of an ass——-e) even if he kept his maiden name, Marion Morrison. No true Irish person takes pride in that low-class insult ('The Quiet Man') to Ireland and I hope Maureen O'Hara is not in a place where she has to watch it and I hope Wayne is.”

The Quiet Man statue in Cong, Co. Mayo

And yet, there is something about The Quiet Man that endures. As Irish Voice columnist Tom Deignan has written, “I have some bad news for the haters. "The Quiet Man" is growing in stature, not merely as entertainment, but as a work of art.

"The sign of any great, enduring story is that it can be reimagined and reinterpreted by younger generations. And so, The Quiet Man – for all of its legitimate flaws – is going to be with us for many more St. Patrick’s Days.”

What do you think of The Quiet Man? Tell us in the comment section and your thoughts may be used in a future article.

* Originally published in Sept 2017.

Comments