There’s a moment in the mesmerizing new Netflix series The Keepers, released earlier this summer, when an attorney from Kentucky describes meeting Catholics for the first time when she was a child.

“We can’t play with you,” the attorney claims the little Catholic kids said. The attorney was not a fellow Catholic, so was a “heathen” and going to hell so, of course, the Catholic kids could not play with her.

This may be a true story but it’s still kind of a cheap shot. It plays on old anti-Catholic sentiments, a sense that Catholics are superior and hypocritical.

Heck, not too long-ago Catholics would have been such a distinct minority in a place like Kentucky that it would have been the local Protestants who viewed Catholics as heathens.

This was my fear about The Keepers overall. It sounded not only grim, but sadly familiar. Sadistic Irish priests with powerful pals in politics and the police department. Lives ruined by oppressive Catholic schools.

And that, partly, is what The Keepers is. But it is also inspirational. And gripping. And an awful reminder of the church’s sins in both the U.S. and Ireland. (I’ll avoid big spoilers.)

If there are any heroes in this story, one is Irish American Abbie Fitzgerald, who’s been referred to as a “Grandma Nancy Drew.”

Fitzgerald attended Baltimore’s Archbishop Keough High School in the late 1960s, and fondly recalls those bygone years. Indeed, one thing The Keepers reminds you is how, not too long ago, the Catholic Church and its large Irish, Italian and Polish families were at the center of big city life.

As we know now, there was a dark side to all of that.

It would be nice if The Keepers -- if historians, in general -- provided a little context to just how important, in positive ways, the Catholic Church was to these people. One reason Catholic parishes were so insular is because, for decades, Catholics were such outsiders in the U.S. that they could only rely on each other (and, eventually, political machines).

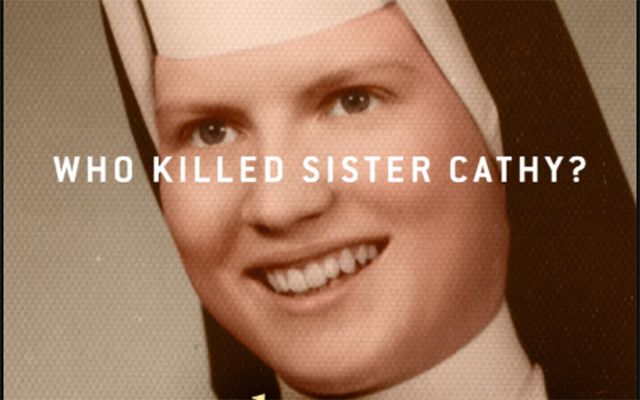

One reason students like Abbie had such fond memories of their years at Keough -- named after Francis Patrick Keough, the son of Irish immigrants, and Baltimore’s archbishop from 1947 to 1961 -- was a young nun who served as a teacher there. Her name was Sister Cathy Cesnik.

In November of 1969, Cesnik vanished. Two months later, her body was finally found. The only thing more shocking than the brutal murder was the fact that the police never found the killer.

Then, after decades passed, former Keough students began “recovering” memories of two sadistic priests at the school.

Father Joseph Maskell is described as coming from a large Irish family, presided over by a matriarch who always wanted her son to become a priest.

Maskell is accused of not only sexually abusing Keough students, but encouraging other priests, politicians and even cops -- Maskell’s brother was a big wig in law enforcement circles -- to do the same.

Once the scandal exploded in the 1990s -- when church officials were still doing everything they could to avoid confronting this problem -- Maskell was shipped to other institutions. He even spent parts of four years in Ireland, where other accusations of abuse have surfaced.

A theory eventually emerges, thanks in part, to dogged research by Abbie Fitzgerald and Gemma Hoskins, that abused students had confided in Sister Cathy, who was going to spill all of Father Maskell’s terrible secrets.

And so, she had to be silenced.

The Keepers is so powerful because while this theory may sound neat, it isn’t. Watch it yourself and decide.

When the long, final history of this dark moment in Irish and Irish American history is written, abusive priests and evasive church power brokers should be brought to justice. But we should also remember the likes of Sister Cathy, who -- if only briefly -- made the world a better place.

Comments